Muromtseva and Pricking the Bubble

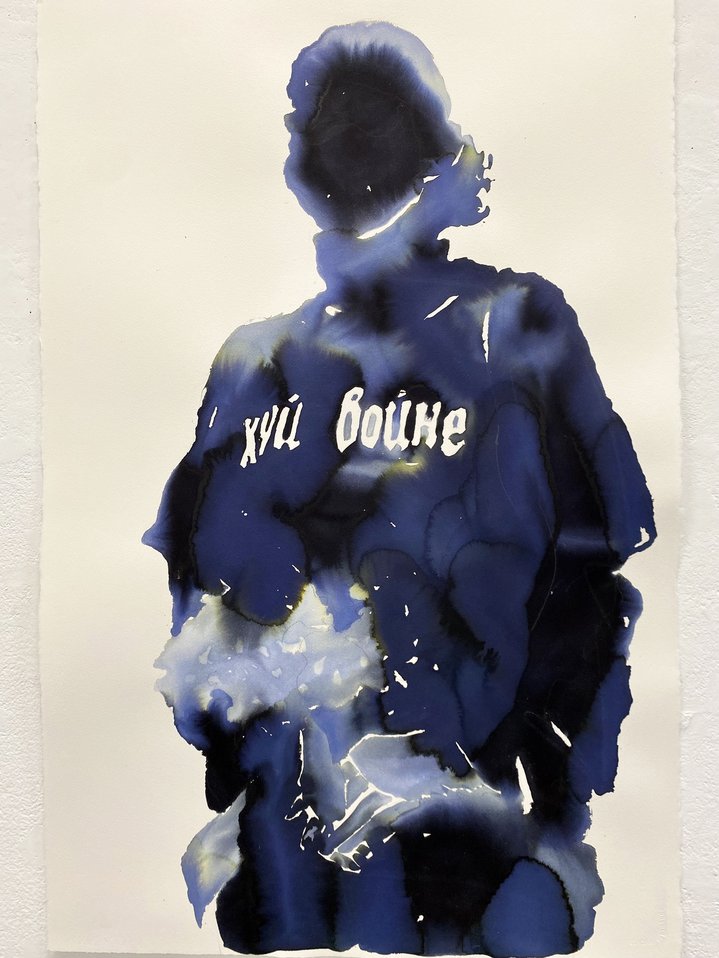

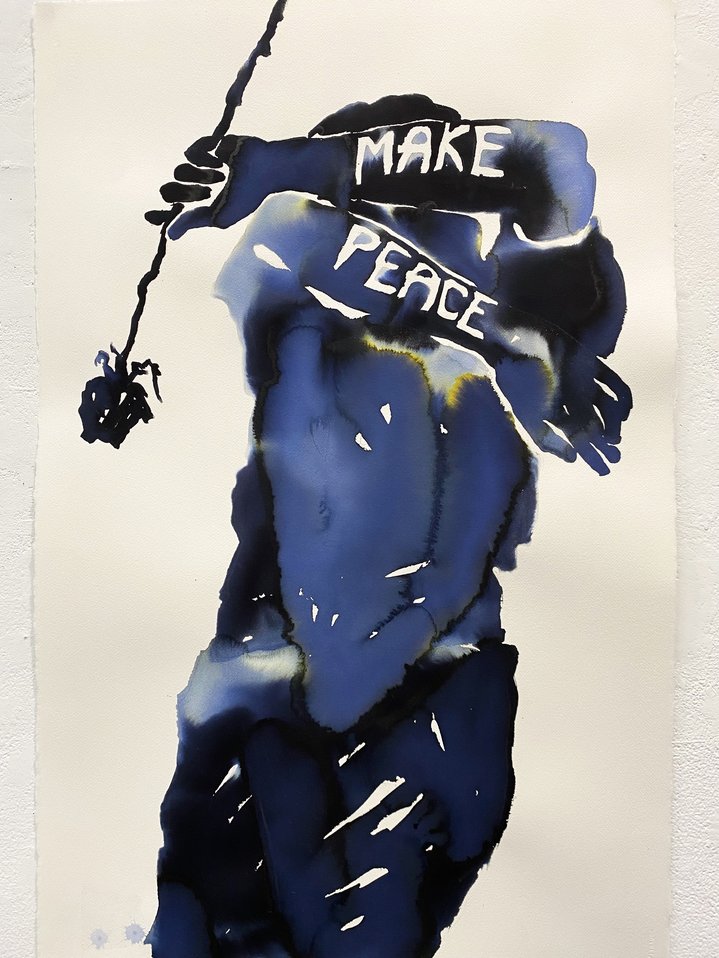

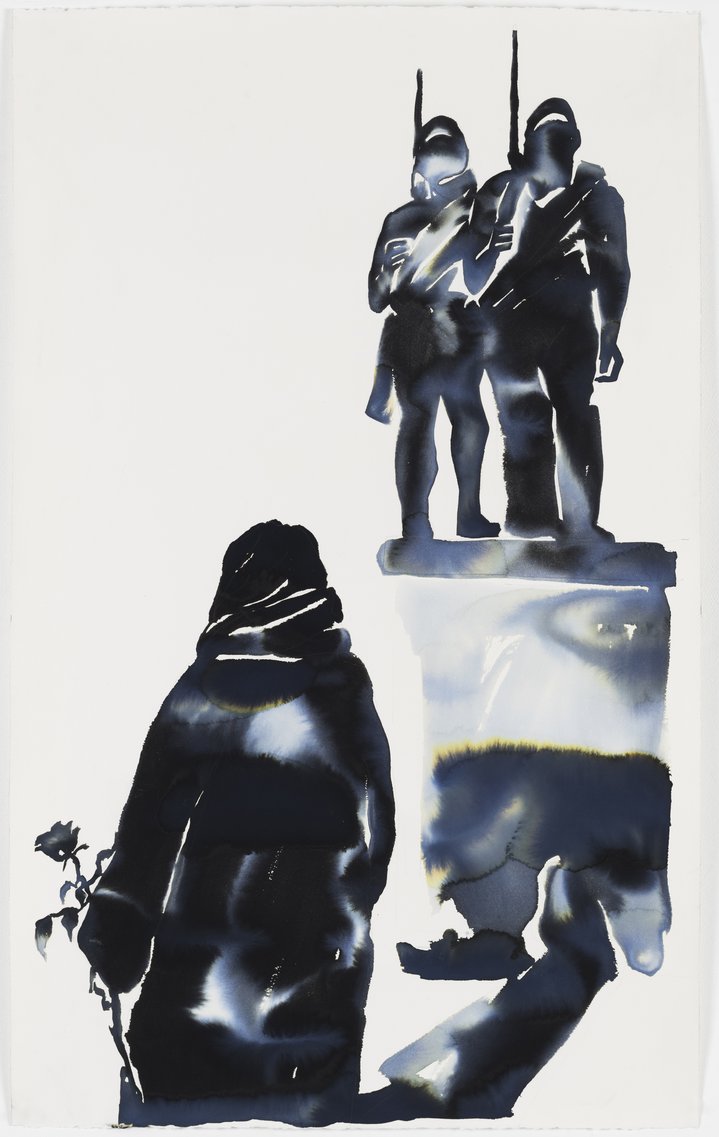

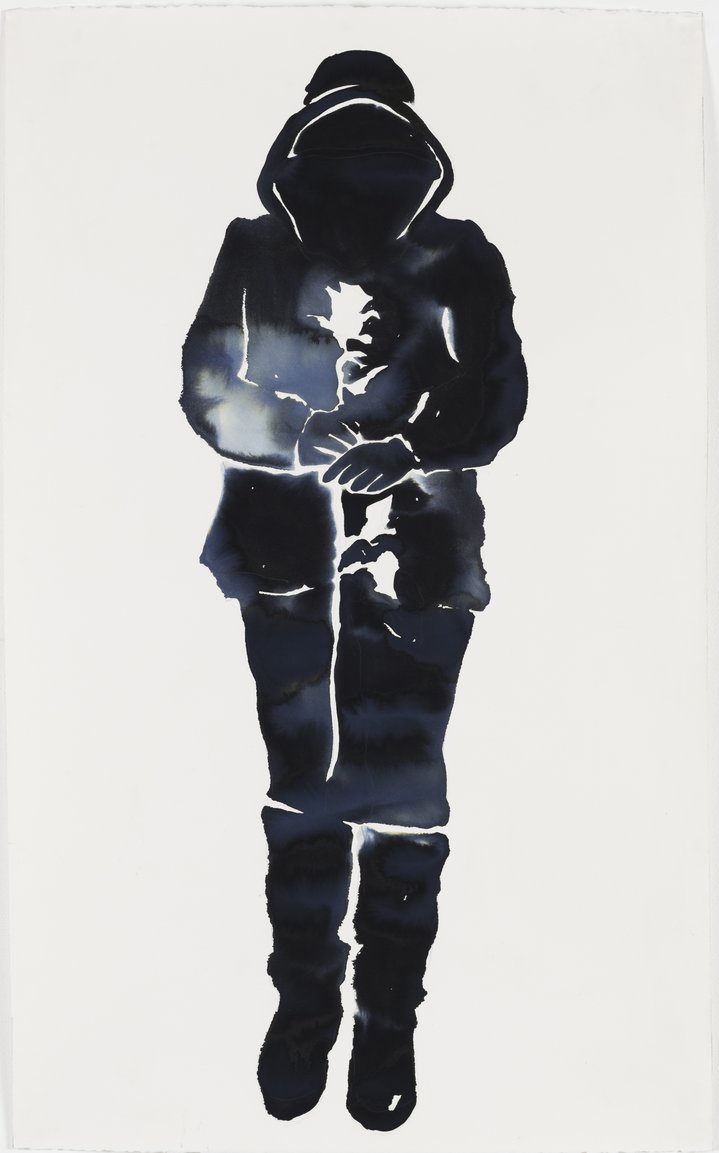

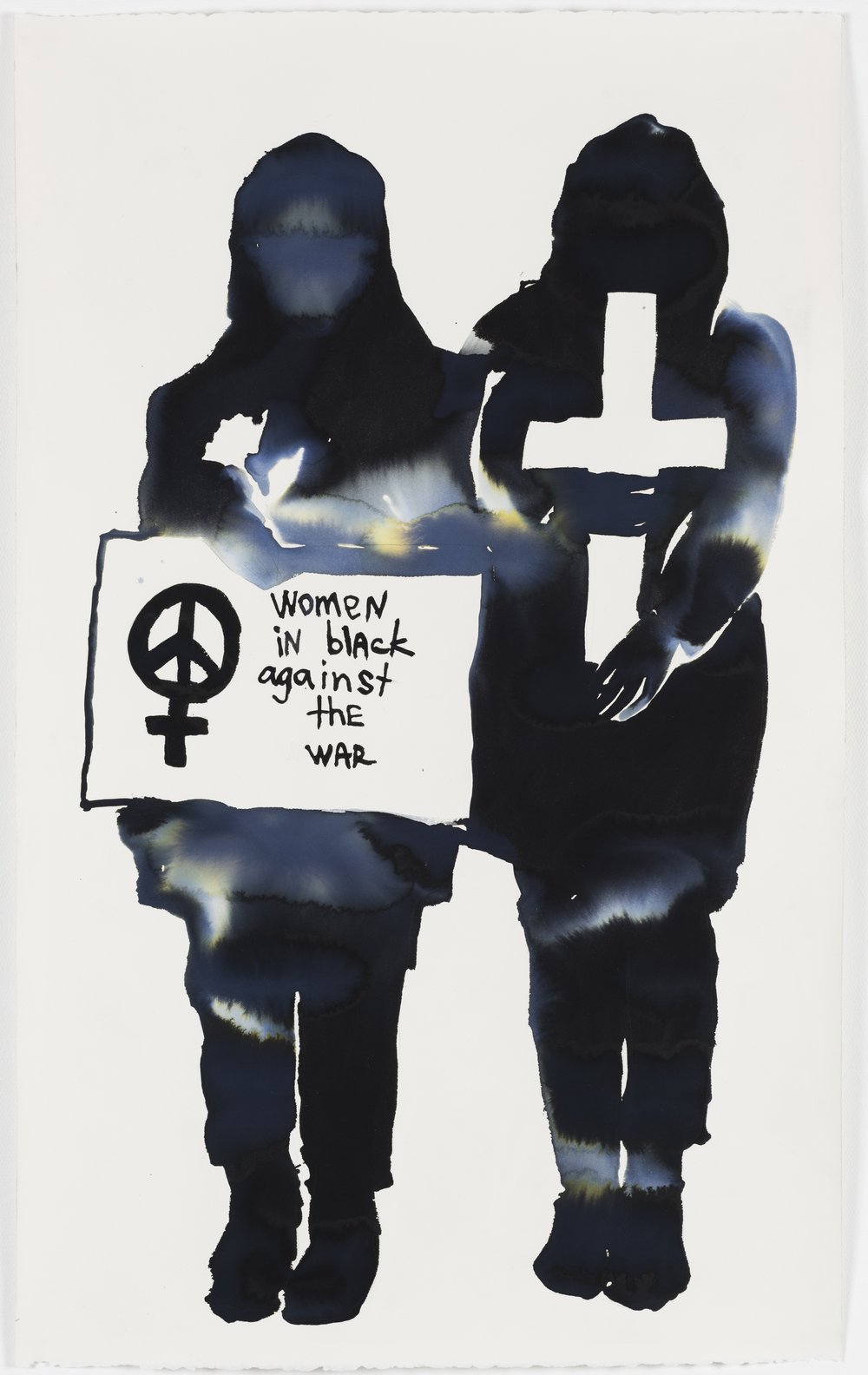

Katya Muromtseva. Women in Black Against the War, 2022. Pushkin House. London, 2023. Courtesy of the artist

Ekaterina Muromtseva is currently painting portraits of the visitors to her exhibition at Pushkin House, London, as part of the protest movement in Russia.

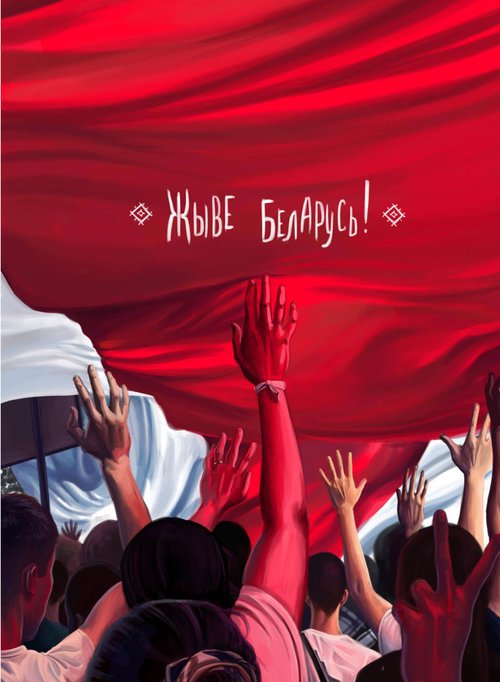

Ekaterina (Katya) Muromtseva (b. 1990) studied philosophy as a sixteen-year-old in Moscow State University and realised that she ’lived in a bubble’. She compared the relative ease of her life to that of her grandmother who had survived the Second World War. Her exhibition ‘Women in Black Against the War’ confronts the current tragedy in Ukraine, but her work goes deeper in its questioning of what can now be viewed as an Ancien Regime. I sat in the ground floor gallery and watched her make a watercolour portrait of another Russian woman. There was a soft steady flow of Russian conversation. The room in Bloomsbury is a white cube, but a rather old-fashioned one: along with the banks of high-quality gallery lights up on the high ceiling there is bold Dentil cornice above a marble chimneypiece. In the upstairs gallery there are watercolours of the women-in-black protesting, but the walls of this clean space are pinned with serried ranks of watercolour portraits of political prisoners: Lilia Chanysheva, Ludmila Razumova, Alexander Nozdrinov, Vladimir Kara-Murza, Sasha Skochilenko, Maria Ponomarenko… The list goes on as to do the sentences to prison: 10 years, 7 years, 10 years, 25 years, 10 years, 6 years.

Bold and simple as this exhibition is, it perhaps does not give full justice to the more subtle side of Muromtseva’s works. I am not yet convinced that watercolour is her most powerful medium. She seems more assured and nuanced in film. Yet over and above everything that she makes there is a desire to work with people, to engage collectively, to escape the bubble. I see connections to the Collective Actions art group but she corrects me to assert that the Kabakovs (Ilya, 193–2023 and Emilia, b.1945) were a true inspiration. After school she wanted to find out more about how her grandmother’s generation lived. ‘I have always been curious,’ she says and so she went off to visit state care homes, lonely places some of them 400 miles outside of Moscow. In one home she discovered that the residents invariably would have loved to follow the old tradition of putting their rugs on the walls but were not allowed to as it was considered too much of a fire risk, so she worked with the residents to paint rugs on their walls. They chose a popular Soviet theme for tapestries, deer in the forest. They called the project ‘Holidays’ 2015. Her collaborative work with the older generation led to ‘Our answers to Moscow Conceptualism’, 2015–19. She asked the residents how they felt about the work of the likes ofthe Kabakovs, Eric Bulatov (b. 1933), Nikita Alexeev(1953–2021) and Pavel Pepperstein (b.1966).

Ekaterina Muromtseva is an artist in flux. Her method of working with people demands such an approach and makes trying to pin down her influences more complicated and perhaps less important. She admits to liking the work of Pepperstein’s father, Victor Pivovarov (b.1937). Indeed, there is more than an echo or two of the ideas floating about in an old people’s home in Viktor Pivovarov’s 2016 Project of Household items for a lonely person. But in my mind’s eye I see her wandering down the dimly lit and desiccated corridors of Ilya Kabakov’s Labyrinth (My Mother’s album), 1990, in a nurse’s uniform. In canvassing opinions about Kabakov one person thought he/they was/were too negative. They would not say the same about Muromtseva. She is in the regenerative spirit of Joseph Beuys (1921–1986). Her curiosity comes with a desire to heal and improve the world. She is prepared to accept that she is not even attempting to find the perfect balance between text and image, content and visual, but rather as someone trying to make works of art with other people where you cannot keep control. ‘Perhaps 30 per cent control is the maximum,’ she says.

The voice of the Narrator in Muromtseva’s film, ‘In this Country’, 2017, is like a cross between Watch With Mother and Big Brother. It is important that it is a woman’s voice. Women played a critical role in the Revolution. The Russian Avant Garde was ahead of its time with the number of leading female proponents such as Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), Liubov Popova (1889–1924) and Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958). The Revolution did give women more rights to work equally with men, but this has never transferred into equality in decision making. It would be wrong to say that women in Russia have nothing to lose, but politically speaking that is true. Artists such as Alisa Gorshenina (b. 1994) fearlessly continue to make anti-war projects and live in Russia, despite the threats witnessed by the wall of portraits of political victims in the Pushkin House show. Last year’s exhibition ‘This Is Ukraine: Defending Freedom’ at the Venice Biennale contained a wall of three hundred photographs of women who had paid a bigger price than jail: they had lost sons in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions in Eastern Ukraine when fighting began there in 2014–2015 (Mothers Series, 2019, by Ukrainian media outlet Mirror Weekly). It is not surprising that women are the most radical.

As Muromtseva explains: ‘The protest movement now is very feminist. The most active group is the Feminist Anti-War Resistance (FAR). (The group was declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities - Ed.) They inspired my works. It is extremely dangerous to protest in Russia, so the protest became very secret. Before 24 February we still had an opportunity to go outside to the streets and to speak up. Now it is not possible. Any sign of resistance is banned in Russia. For example, 12 years old Russian school girl Masha Moskaleva drew an anti-war drawing at school and her father received a jail sentence.’

In this time of crisis Ekaterina Muromtseva is wanting to show clarity. Ironically, I mentioned ‘the special operation’ in Ukraine but she was having none of this. When the stakes are so high, there is no room for irony. The political rights of women have been going backwards in much of the world. The Pushkin show has a strong echo of the brilliant exhibition earlier this year at the Barbican Curve in London in which Iranian-born British artist Soheila Sokhanvari (b. 1978) made beautiful pictures of the brave women who have been fighting in Iran for their rights, and for others’ rights, for decades.

I yearn for the day when regimes are no longer bullying their own populations. One senses in such circumstances Ekaterina Muromtseva might allow a little more ambiguity in her art. In sheer aesthetic terms the walls of portraits that Anselm Kiefer (b.1945) produced in the 1980s were more powerful, but then he was accused by some of glorifying war. He certainly chose more male Romantic heroes than female. Both art and politics need to change.