Communicating Hidden Narratives in Russian Photography

Nikita Shokhov. Moscow Night Life series, 2010–13. Ruarts Foundation collection. Courtesy of Ruarts Foundation

A new exhibition called ‘Communication’ at the Ruarts Foundation in Moscow uses archives to explore alternative histories of Russian photography, revealing how throughout history conventional representations of communities have created fascinating mythologies of the Other.

As part of the inaugural Biennale of Private Collections, Ruarts Foundation in Moscow is staging a show called ‘Communication (Another History of Russian Photography)’. Curator Daria Panayotti has assembled photo archives from the nation’s leading private collections and institutional foundations including Ruarts, MIRA and MAMM, which platform different artistic groups and communities, based on family, friendship, or professional ties. What emerges in these images is a microcosmic, alternative history of photography far from mainstream, but with a certain charm and appeal.

Spread out over three floors in the foundation’s distinctive building, exhibition designer Konstantin Larin has constructed various dioramas and small cabinets and hermitages throughout the space, in which the images on display can even catch their own reflection in mirrors. On each floor, there are small purpose-built enfilades of rooms which prepare visitors for the kind of private, intimate conversations they will be privy to in the archival images on display.

Observing diverse communities and circles of communication, whether in early 20th century silver gelatin prints, digital photographs from the second half of the 20th century, or those generated by artificial intelligence, you dig up an interesting leitmotif: the photographic gaze on a specific community or group always creates some mythology of the image of the ‘Other’. This gaze is the director of its own performance, in which a person becomes either an obedient marionette in a puppet show, an alien from virtual worlds, or a character from Soviet and post-Soviet cinema.

Curator Daria Panayotti puts forward an interesting idea: “the sense of community is more a result of social imagination than a given reality”. Vintage group photographs of high school graduates, college students, or military department officials are all based on the genre of group portraits of 17th century professional guilds. Each individual person is shown clearly, and together they form a multi-facetted collective body, a social construct designed to testify to the strength of society, the state, and its traditions and laws. This way of depicting groups in photographs is still commonly used today - from pre-revolutionary prints of group portraits presented in display cases, you move through the Soviet era to the recognition boards of production leaders and finally to group portraits of today's college graduates.

Curiously, in the pre-revolutionary archives there are errors visible in many of the photographs. Portraits covered over with white paint; in the middle of an image a sheet of photographic paper is bent, so the group portrait cannot be seen properly, hidden by what we call a trompe-l'œil, a visual trick. Such mistakes correlate with a concept introduced by Roland Barthes of ‘punctum’ - stabs of reality that cannot be “corrected”. These glitches and failures become cuts in an otherwise ordinary perception of the world through which both the pain of loss and the full-blooded energy of life, (neither of which can be subjected to social manipulation), seep through.

In the early 20th century, an eccentric photographic studio called ‘Monster’ in Moscow made photomultigraphs as a form of entertainment for the masses. They were photographs of a person taken from several angles: “you in your own company”. This schizoid splitting of the personality predicts many psychoanalytical themes in the modern era, including catching oneself with the gaze of the Other and errors in the classical representation of the image.

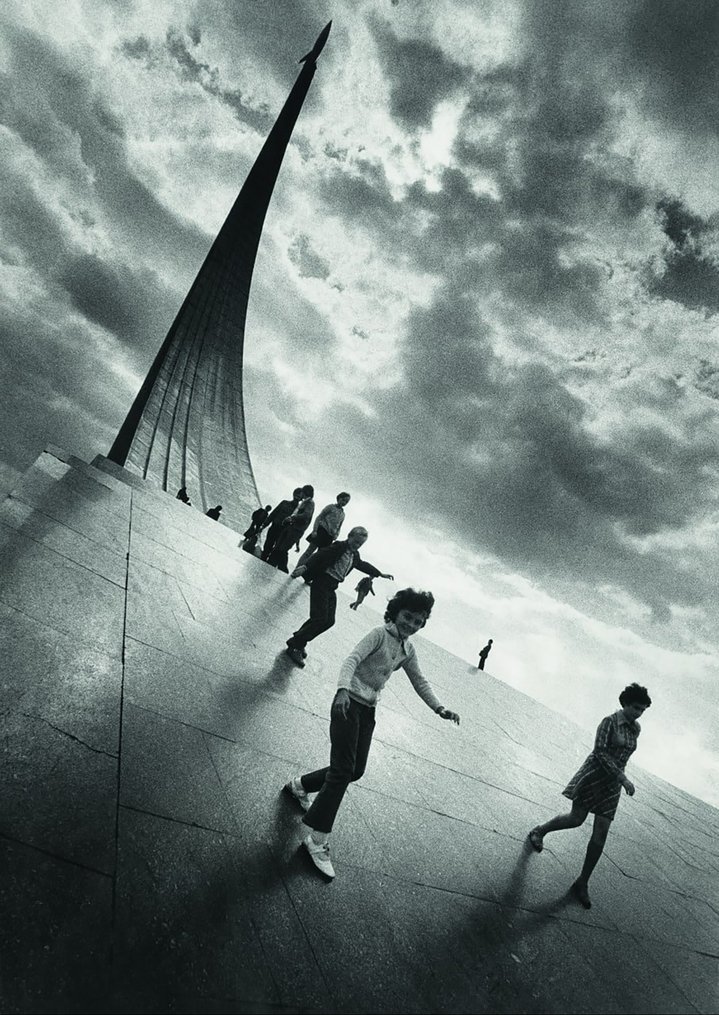

In the USSR, the manipulative tactics of Soviet photojournalists presupposed an appeal to images of human masses obedient to and controlled by ideology. The masses literally became objects of social plasticity: the huge parades depicted in photographs by Nikolai Yanov (1903-1982) and Viktor Akhlomov (138-2017) are formed into geometric abstractions, illustrating Boris Groys' insight that socialist realism was “avant-garde in a Stalinist way”.

Again here, errors and glitches that destroy the hypnosis of ideological manipulation with corporeality are interesting. In her 2011 series ‘Family Portrait in Interior’ Vita Buivid (b.1962) photographed her subjects with their backs turned to the camera. This creates strange, anxieties in the viewer a bit like suspense in a psychological thriller, leading you to involuntarily reflect on the reverse, dark side of the family idyll.

In her 2000 photographic series ‘Light is Coming’, Russian artist Olga Chernysheva (b. 1962) depicted crowds of anonymous people on the streets or in vehicles, also showing them from behind. And a colourful carnival of post-soviet exotic hats unfolds in front of the observer - the fiery patterns, with pompoms, ushanka hats made from fossilised rabbits, synthetic scarves and hoods. This carnival of hats can be compared with exotic flowers, or cacti in curious orangeries. And in post-Soviet society, such a parade testified to a strange attempt by people to reclaim a sense of identity in a world where common ideologemes and attitudes had collapsed.

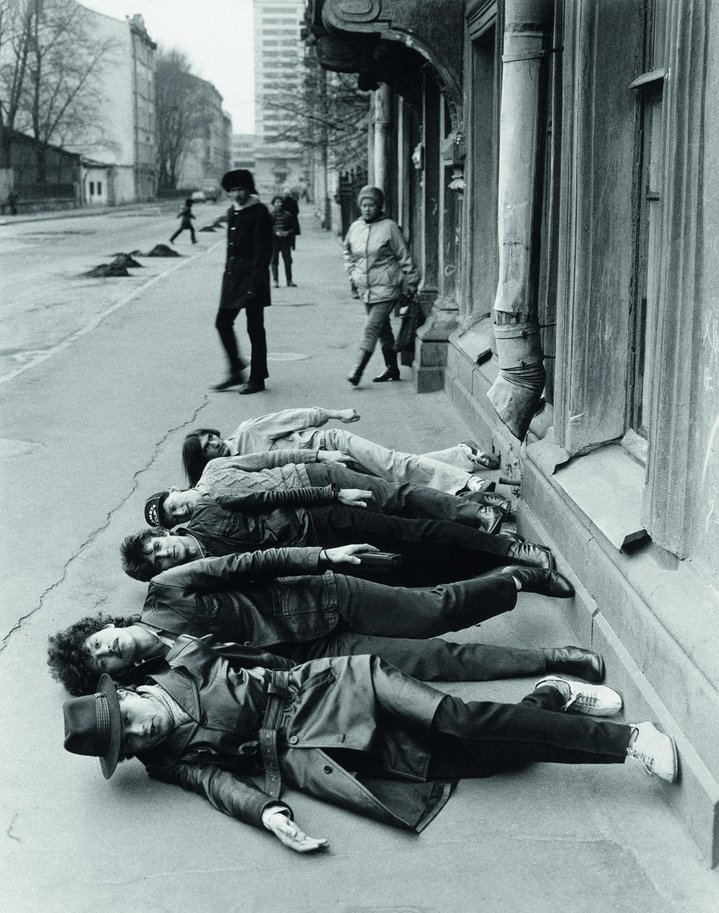

The exhibtion goes on to look at urban communities. In the 19th century, Romantic writers like Nikolai Gogol and Vladimir Odoevsky looked for the Image of the Other - a kind of double or werewolf - in amongst the hustle and bustle of the city. And during the heady decades of the 1990s and 2000s in Russia, classics of contemporary photography Igor Mukhin (b. 1961) and Sergey Borisov (b.1947) similarly searched the streets of Moscow and St Petersburg. In Sergey Borisov's iconic photographic work ‘Dialogue’, the musicians appear to walk in line yet are bizarrly lying on the ground in a radical disruption of the grid of normal spatial coordinates. The fantastical ‘otherness’ turns out to be the looking-glass world of the usual order of things. In a photograph by Igor Mukhin, Oleg Garkusha, the leader of rock band Auction, stands on the corner of Olminsky Street like a comic villain from the silent cinema, or a punk escaping persecution by Komsomol members. And today, groups in Russia who are seen as estranged communities, as representatives of the “other”, are popular dramatic subject matter for artists and photographers.

A panoramic school graduation party by Alexei Slyshev clearly inherits the aesthetics of Igor Mukhin. The representation of various emotions and expressions which you can pick out from within the gloom does not at all testify to the triumph of an ‘honest’ objective gaze. The pantomime of the lives of adolescents passes through the visual codes of cinematography and gives a certain sublimated emotion of carefully performed roles within a celebratory mood.

The exhibition concludes with images created using neural networks. In collaboration with AI, Fedor Maximishin (b. 1991) mixes nostalgic themes combining Soviet citizen with deadly monsters in gaming consoles and fantasy novels. What comes out of it is something that resembles the popular TV series ‘Eterna’, whose aesthetics are defined by Hollywood blockbusters like ‘The Lord of the Rings’, post-punk gloom and trash framed by Soviet sentimental ‘midshipmen’ and the ‘three musketeers’ by director Georgi Yungvald-Khilkevich.

Now, increasingly the idea of community is dissolving in favour of radical individualism of creating one's own worlds of communication, in which themes of manipulation and the image of the Other are already reflected upon and understood as allies.