Expat Photographers Reinvent Themselves in Israel

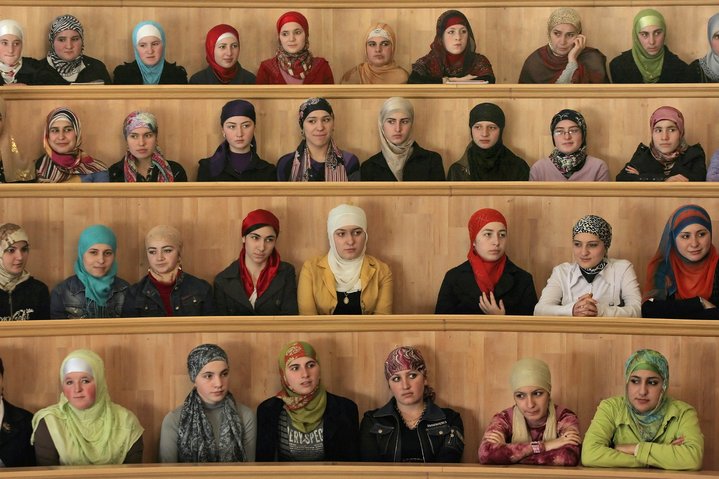

Dima Konradt. Untitled. Israel, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

Exploring the effects of emigration on the work of several photographers who left behind established careers in Russia to settle in Israel after Russia’s invasion to Ukraine, Natalia Kopelyanskaya follows the experiences of Sergey Maximishin (b. 1964), Dima Konradt (b. 1954) and Alexander Sorin (b. 1965), and looks at how their artistic practices have changed as their lives have been upended.

Back in March 2022, as the armed conflict which has come to define our times was set in motion, the state of Israel quickly opened its gates to fast-track repatriation. Since then some seventy-five thousand new Israelis have settled in the country from across Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. Conscious emigration is a difficult, complex process on many levels, and repatriation perhaps is more so because along with all the civil rights and new obligations as a citizen, repatriates face head on the question of how to acquire a new identity. In Israel with its historical and political peculiarities regarding the creation of the state of Israel this can be challenging for those in the liberal arts. And then there is the sudden lack of one’s familiar support system, network of peers, audience and loss of a sense of shared community.

Over its seventy-five-year existence, Israel has been in a state of armed conflict which defines every aspect of life. Israeli artists are highly politicised. There is the combination of state and religion, the phenomenon of ‘island mentality’ and being surrounded by enemies, a ‘small bubble’ family structure of society living in a very small space, conservative cultural policies and increasingly high costs of living. The local art world is hermetic and tightly organised; it has strong connections with the US and Europe. There is no demand or space for newcomers. With entry into Israeli art society beyond the reach of most, new repatriates mostly turn to their own resources and are setting up their own scenes in the big cities, Jerusaslem, Tel Aviv and Haifa. It is far from easy and many are in constant survival mode, living not by their art, but by physical labour - working in construction, and factories, or even cleaning.

Art Focus Now talked to three photographers whose names and whose work are well known in Russia: Sergey Maximishin (b. 1964), Dima Konradt (b. 1954) and Alexander Sorin (b. 1965), to find out about their new life and professional outlook in Israel.

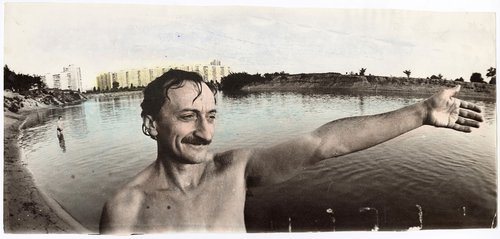

Sergey Maximishin

Award-winning documentary photographer Sergey Maximishin, himself a renowned collector of photographic art, had already considered moving to Israel back in 2021 after the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny. Since 2022 he has been living in Jerusalem as his family is half-Ukrainian, and with close relatives living in Kyiv, he felt he could not stay in Russia. Still, repatriation was a step in the dark, he had no plans or vision as to how his life might evolve, it was an “experiment with unclear goals” as he puts it today. Maximishin is one of the lucky ones as he has family and friends around him in Israel as well as a large audience online. At the same time he is making efforts to get to know local photographers and educational art institutions. He brought a huge cache of printed works with him for sale and exhibition but he has not received even one enquiry or request.

In his opinion, in Israel the typical trajectory of a professional photographer is unlike that of Europe or the USA. In the latter, photographers start working for photo agencies, and then work for big magazines, but in Israel a successful photographer ends up working for agencies, considered the pinnacle of their career, there are no big magazines in Israel.

Maximishin spends a lot of his time teaching and has kept on many of his students, it’s a “safety cushion" he enjoys. As well as continuing to teach his own courses online across different countries, he also has a group of Russian-speaking students at the Thelma Yellin High School of Arts.

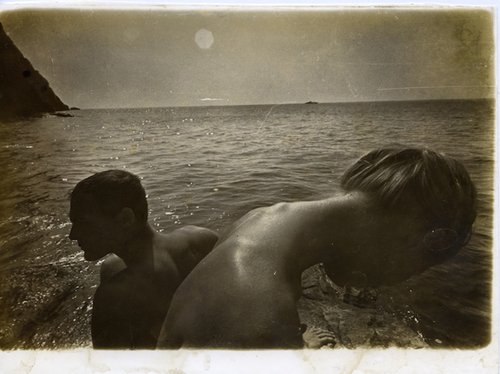

An important part of his photography collection comprises vernacular Soviet photography – amateur, reportage photos from the 1920s onwards. He likes the immediacy and authenticity of images taken by neighbours or work colleagues. Some time ago he planned to publish this material and commissioned Russian historian Mikhail Melnichenko to write texts for the images, but he cannot finish it now. He has turned away from images he once found charming, “For me it is as though I were to publish amateur German photographs in 1944!"

Despite this new stage in his life and the compexities of the current situation, Maximishin still sees himself as a Russian photographer. One who has worked all over the world, yet whose professional identity is undeniably Russian, and Russia is where he has done his best work. For now, in Jerusalem he feels like an observer, a tourist in the Old City, but he is making steps to integrate, he is learning Hebrew, has a new routine. His greatest dream is to return to Russia and put a monument on his father’s grave.

Dima Konradt

Dima (Dmitry) Konradt is a big name in Russia among independent (non-conformist) photographers and most associated with St Petersburg where he is known for photographs of the Leningrad rock club in the 1980s. Today he is a recognised as the founder of the new colour photography school where colour is self-content and the creative source. He has exhibited widely, created his own idyosyncratic artistic langauge, and his works are in major museum and private collections. Konradt came to Israel at the end of 2021 to visit his children, who had already repatriated there, and in 2022 he and his wife decided not to return home and settled in Tel Aviv. He never felt uncomfortable in Russia, but he was ideologically opposed to the regime there. He is finding the transitory state hard, where St Petersburg is no longer home, and he does not feel yet at home in Israel, but he has no doubts about his decision to leave.

Since moving to Israel he has dropped his full name Dmitry in favour of the diminutive ‘Dima’. He tells me he has been focussing most over the past year and a half on adapting to the light and colours of his new working environment. He has acquaintances among the more established Israeli Russian-speaking photographers such as Shlomo Bronstein (b. 1962), Alexander Bronfer (b.1963), Dmitry Brickman (b. 1964) and Mikhail Levit (b. 1944). But one of the biggest questions for him remains unanswered: how to carry on with his life long project of "observing the life of light"? He has no idea yet how to move forwards and he does not feel ready to come up with a new idea. After the initial honeymoon period in his new homeland he finds himself taking his camera out less often although it is always with him. He feels that some internal balance inside him has been disturbed and confusion has set in.

Like Maximishin he has students, and teaching has become even more important to him since arriving in Israel. For Konradt his circle of students is not his school, he refers to his student chat group as ‘Vision Tuning’ and they are spread across Europe, in France, Germany and St Petersburg. What lifts his spirits most in Israel are his friends, like Sergei Maximishin and he loves Alexander Bronfer’s pictures of the Dead Sea.

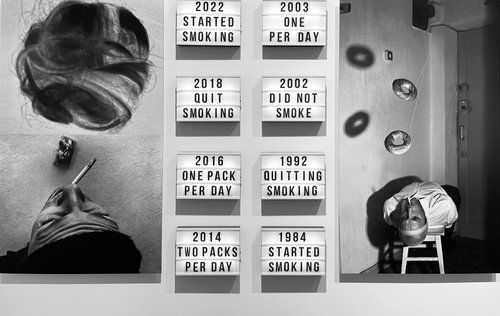

Alexander Sorin

Alexander Sorin is a well-known Moscow photo editor and photo correspondent who has worked for numerous media outlets. He was head of the Russian photo competition ‘Pryamoi Vzglyad’ (Direct View), and has participated in and curated many exhibitions and multimedia projects. Sorin is no newcomer to Israel, in 2013 his photos were published in Vokrug Sveta magazine for Israel’s 65th Anniversary. Since his arrival in 2022, he says he has few expectations and that he feels there is little space for him in Israel. He finds the local scene relatively narrow and thickly populated with local professionals leaving no room for outsiders and anyway fluent Hebrew is needed to be a photographic reporter.

Although Alexander Sorin sees his place in a larger international pool, choosing not to be defined by any specific national school, in reality his area of expertise and field of interest has always been Russia. He feels its loss acutely, and even expresses gratitude that former colleagues of his who have not left Russia carry on recording how the country has changed from within, such as Alexander Gronsky (b. 1980) and Dmitry Markov (b. 1982).

For now, Sorin prefers not to engage in photography as an art form, but to use it for research purposes, as a way of keeping a diary and recording his own experiences. And he says he is open to new projects, currently he is exploring the possibilities of a large visual anthropological project dedicated to repatriates from different waves of aliyah in Israel from the 1930s to the present day. “My own field may be lost but there’s time to think”, he says.

It seems that for all three photographers, as for the plethora of artists from across Ukraine, Russia and Belarus who have recently fled their homes, this is a time for exploring the new. What is clear: after a year and a half there is no way back. The only way is forward.