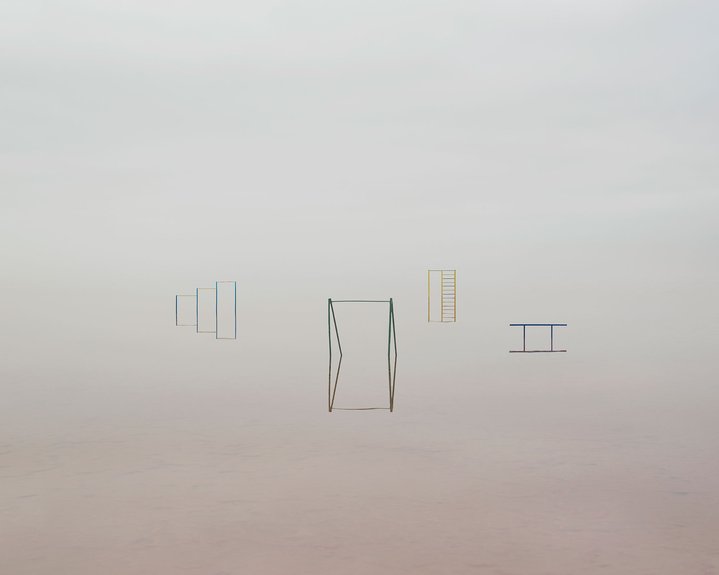

Danila Tkachenko. Drowned #4, Cultural Center, (Montenegro). 2021 © Danila Tkachenko

A solo exhibition of this Russian artist and photographer, who won the World Press Photo Award, is opening at Moscow’s Lumiere gallery. It features work from three of his latest series, which are all united by a signature meditative mood.

In 2020, while much of the world was sequestered at home in lockdown, Russian artist Danila Tkachenko (b. 1989) was, too. But he was also already somewhere else.

Tkachenko had relocated to the shores of the Aral Sea, a body of water edged by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. But, in theory, he was nowhere; that is to say, he was trying to realize images of nowhere. Infamously and tragically, the Aral Sea dried up during the Soviet period. Water from its two river sources, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, was deliberately diverted to transform the Central Asian steppe into a territory for the production of cotton. The result of this megalomanic dream was an ecological disaster. Tkachenko found himself there for extended periods of time throughout 2020 and 2021, fascinated by what he considered to be the area’s emptiness and seeking others with whom he could collaborate.

The results of these endeavors will soon be on show at the Lumiere Gallery in Moscow. The show, titled ‘Fragments’ is Tkachenko’s first collaboration with the gallery. Three series, ‘Planetarium’, ‘Shoal’ and ‘Drowned’, will be on view. Both ‘Shoal’ and ‘Drowned’ draw from Tkachenko’s own experiences at the Aral Sea. In ‘Sanatorium ‘Friendship’ Ukraine’ (2021), an eerie nothingness stretches in all directions. Only a slight textural difference distinguishes the overcast sky from the murky stillness of the water. But, in the centre is a cut-out of the iconic sanatorium, a Soviet-era construction, which tilts like a ship sinking into the sea, impossibly leaving no waves. In another image, ‘PO-2 Series Fence’ (2021), a long gray strip of fence sews a tight seam between sky and sea. When viewing the work from a distance, we lose a sense of depth and the identity of the object ceases to matter. Imagine what the world would be like, these photographs seem to ask, if there were no places.

Like much of Tkachenko’s practice, the argument in these works arises from the tension he stages between recognition of an image and its abstraction; between its placement in a specific context, often through his titles, which is then made general in his depopulated, monochromatic images. This play between reality and utopia (or dystopia) has found resonance with audiences and may in part stem from Tkachenko’s background. Before he devoted himself full-time to his art practice, he worked as a photojournalist. Disappointed with the profession, he began to study at the Rodchenko School of Photography and Multimedia. His work is widely exhibited abroad; he was a finalist for Russia’s Kandinsky Prize in 2017; and received a World Press Photo Prize in 2014. He is perhaps best known for his controversial project ‘Rodina’ (“Homeland”), in which he worked with local authorities to immolate, and photographs of abandoned wooden houses in northern Russia.

In conversation, Tkachenko speaks softly, but with intention. How does he respond to criticism that his work might verge into “ruin porn”, an epithet that here would imply an image that plays on the West’s pleasurable fascination with the destruction of the East? Or that his work skirts the fact that some of the “empty” or “dead” sites he photographs are in fact still inhabited and used? For example, the “Aral Sea” is in fact two seas. Thanks to a revitalization program by the Kazakh government and World Bank, the northern half is recovering with revived fish stocks. “I think post-Soviet space is filled with hauntology, many utopian ghosts,” he tells me. “This is what my work is about – these ghosts — it’s a kind of profanation, printing out these objects on a foam board in a ‘nowhere’ place. Nostalgia for the Soviet past is a tool of the Putin regime that generates war. For me, it’s more important to me to expose nostalgia than to reinforce it.”

The essence of the work, he suggests, is not to make viewers nostalgic for a lost past, but to make them question why and for what purpose they are longing. His strongest images thrive in a kind of metaphorical and literal gray area: as in ‘PO-2 Series Fence’, when reminders of the past hover between simple geometries and an inhospitable place, where almost nothing grows and dangers abound.

Fragments by Danila Tkachenko

Lumiere Gallery

Moscow, Russia

February 11 – September 4, 2022

Visits are by appointment on weekends only