A Chagall Show for our Times

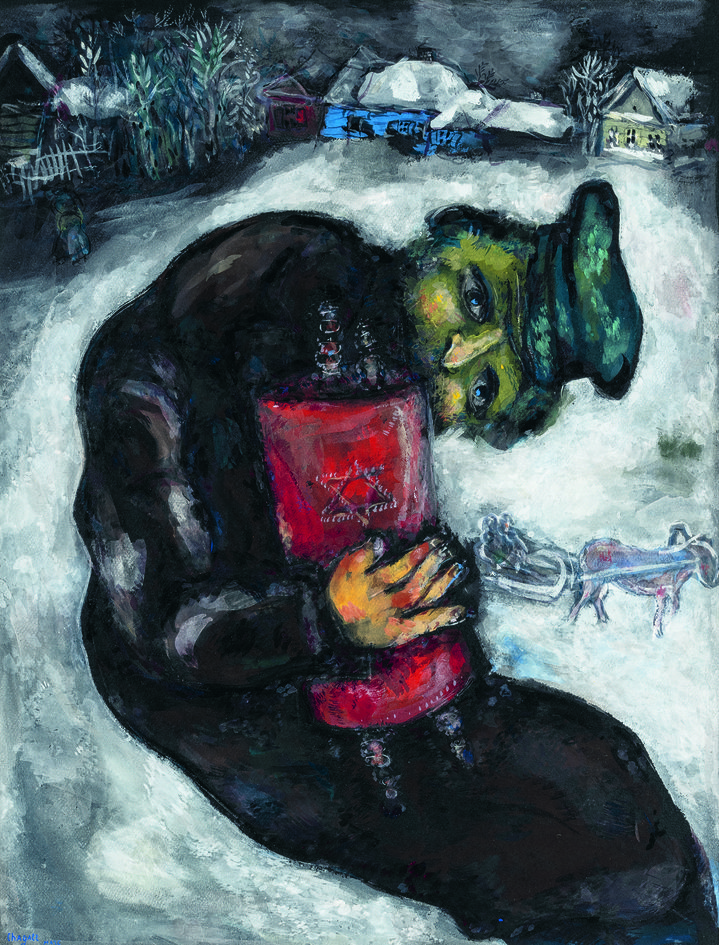

Marc Chagall. The Cattle Dealer, c. 1922-1923. Courtesy of VEGAP, Madrid and Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Migeat

Curated by Ambre Gauthier and the artist’s grand-daughter Meret Meyer, ‘Chagall. Un Grito de Libertad’ at the Fondacion Mapfre in Madrid is an essay in a socio-political reading of the art of one of the most apolitical of outsiders.

There is a sense that ‘Chagall. Un Grito de Libertad’, (A Cry of Freedom), is an exhibition curated for our times, with the central focus on the turbulent, socio-political backdrop to what was the long and eventful life of Marc Chagall (1887–1985). With its wars, revolution, displacement and, culminating in the holocaust, the first half of the 20th century was one of the most tragic episodes ever in the history of humankind. Until recently many of us thought that bloodletting in Europe accompanied by deep macro geopolitical tensions was consigned to history. Here we are a century later, widespread instability and conflict, spilt blood, a different era but nonetheless a troubling state of affairs.

To some extent, curators always reflect the values or preoccupations of their current times, so this new socio-political reading of Chagall’s work does not come as a surprise. If it is the curator´s task to create a narrative or narratives through works of art, this exhibition ticks that box, following chronologically the big historical events he lived through, drawing on detailed archival research, harnessing works relating to events, supported by visual documents from the artist´s life, like his French passport stamped ánnule´ when his French nationality was revoked because he was Jewish during the Vichy government, or the photographs of Chagall and his wife Bella unwrapping the paintings they had shipped from France to New York in 1941. The curators set clear limits to their scope, examining the socio-political background to Chagall´s life exclusively through the lens of his own works, here you find no works by his contemporaries or photographic or video material documenting the large historical events behind his paintings. It is enough, the curators imply, that Chagall is the great witness. Perhaps this is both the key to understanding this show and yet its Achilles heel. Certainly, unlike his close contemporary Henri Matisse (1869-1954), much of Chagall’s work is a document of the age in which he lived, and you could take the exhibition literally as a potted history lesson. And yet Chagall is far from a contemporary historian, nor does he make overt political statements like Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) did with his 1937 ‘La Guernica’. If there is something political about his art, which I think there undoubtedly is, a cry for freedom is an appeal to our collective responsibility to stop ‘man’s inhumanity to man’.

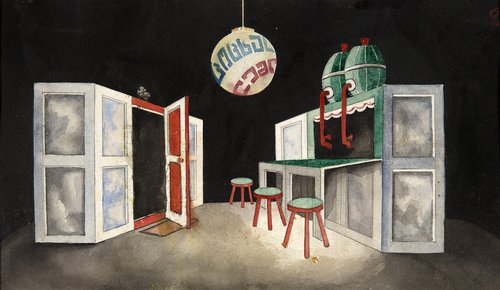

The circus and la commedia dell’arte are two themes in which Chagall found the perfect metaphor for the colourful yet tragicomic spectacle of our collective lives in modern societies and the exhibition starts with the monumental 1959 ´La Commedia dell’Arte’, he made for the Frankfurter theatre, a commission he accepted just two decades after his picture of a Rabbi had been burnt by the Nazis in Mannheim and his paintings were exhibited in Munich as Entartete Kunst. It was the late 1950s, it was the era of post-war reconstruction in Europe and a time for reconciliation and Chagall depicts himself in the guise of a large one-eyed red rooster peering out at us, the spectators. Forever the great witness, he reminds us of what he has seen and experienced lest we forget.

Perhaps in a rush to emphasise their socio-political reading through historical events, the curators do not dwell much on the artist’s origins, his childhood and his roots in the shtetl of Vitebsk (the room dedicated to Russia covers mostly the time in his early 30s at the Vitebsk People’s Art School). Chagall´s parents were poor, his father sold herrings and his mother had a grocer´s shop, as a child he watched them with a sense of horror as they struggled to make ends meet in the pre-industrialised, pre-revolutionary Russian Empire. Later, in his autobiography he recalls himself as a boy standing in the cemetery over his mother´s grave, ´Here is my soul. Look for me here; here I am, here are my pictures, my roots. Sadness, sadness! ´. The colourful characters in his paintings are drawn from his family, his bearded grandfather who taught religion, the other a butcher, and among his half a dozen uncles his violin playing uncle Neuch with whom Chagall as a small boy would sit on a horse drawn cart riding through the countryside around Vitebsk. There was the daily life in and around the synagogue, the rituals on the Sabbath. Industrialisation, revolution, persecution, war and emigration all shattered and destroyed that life, and lead to a new state of uprootedness.

‘Chagall. Un Grito de Libertad’ came to the Mapfre in Madrid from La Piscine, Le Musée d’Art et d’Industrie André-Diligent, Roubaix, and after it closes in May it will move to the Musée National Marc Chagall in Nice. Much is made of the fact that this presents Chagall’s work in a new light, although only last year there was an exhibition at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt called ‘World in Turmoil’, which focussed on his work of the 1930s and 40s, it seems that audiences today want to look back at the life he endured, perhaps we are searching for our own answers. ‘Chagall. Un Grito de Libertad’ is far more encompassing than the Frankfurt exhibition, covering his complete artistic journey, from Vitebsk to the monumental crucifixion works he made for stained glass windows in the South of France when he was in his seventies and finally living through a more stable era. At the Mapfre in Madrid before the opening curator, Ambre Gautier questions how political Chagall was, answering herself that he was not political, that he was a dreamer but that you can see in these works a cry for a different kind of world and therein lies a new reading of his work which is important to note. ‘It gives a complete reading of his work’, she concluded.