In search of Marc Chagall

The exhibition ‘Marc Chagall. World in Turmoil’ opens at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt showing more than sixty works created by the artist in the 1930s and 1940s. Remarkably topical, it is less about dreamy fantasies and more about the tragedies he experienced.

"Consciously, voluntarily creating fantasy art is completely alien to me," Marc Chagall (1887–1985) confessed in an interview with L'Art vivant in Paris in 1927. “From this perspective, I have nothing in common with artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Bruegel the Elder or Odilon Redon. Their fantasy is imaginative, desirable, symbolic, often literal, but it is not real". By then Chagall was already famous, and had established his presence in Paris and had decided it was time to label himself as a French artist. He had first come to Paris in 1911, at the age of 27, living with the future coryphaei at La Ruche (The Beehive), and had it not been for the war, the birth of his daughter and his infatuation with Communist ideas, Paris would always have remained his home. So the move there in 1922 was a return. And not to an empty place - commissions were waiting for him. Fate was generally kind to Chagall: he lived a long life, won fame and, over time, wealth. Hence the widespread belief that Chagall was a happy soul. But this was not always the case.

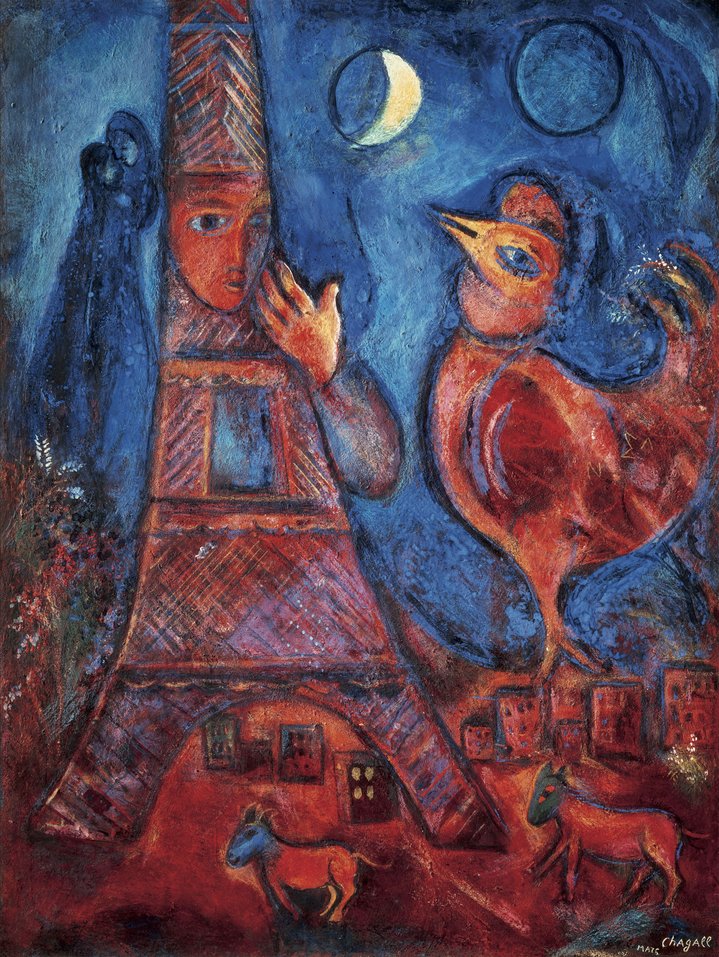

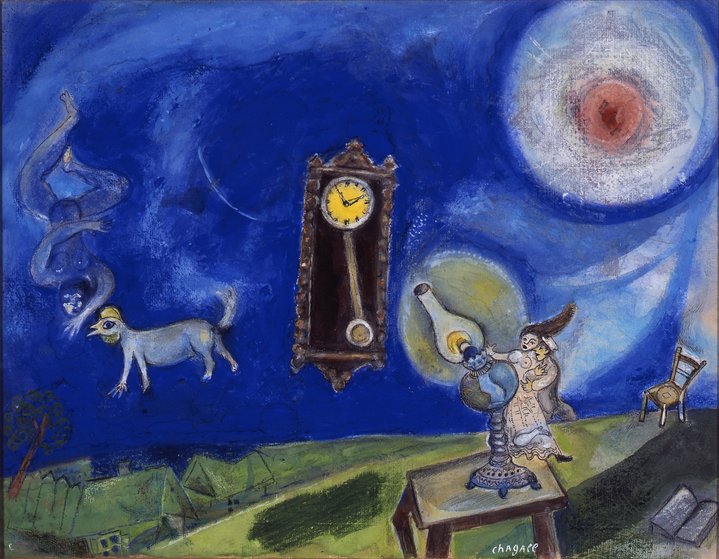

People see flitting in the clouds of his visions filled with the streets of his native Vitebsk the face of his beloved Bella, elders saving Torah scrolls and goats playing violins in the moonlight, and assume that Marc Chagall left no room for reality in his art. In fact, this fictional world, manifesting itself in a blue mist, is a blatant reality: it was a terrible life with a destructive war. In this reality, you need an angel, and so here is an angel.

The exhibition in Frankfurt am Main makes all this clear. Curator, Dr Ilka Wehrmann, chose the same quote from an interview with L'Art vivant to open her text for the catalogue. She saw in these works "the artist's search for a visual language in the face of exile, persecution and emigration". It is meaningful that in the 30s and 40s "Chagall turned more and more to the Jewish world in his works".

Wehrmann explores the artist's Jewish identity, putting it at the heart of everything, something that has never been emphasised in this way in Chagall exhibitions at the Pompidou Centre or MOMA, or in any other large art museum to stage a Chagall solo show. Museums have of course always noted the artist’s Jewish background, however, details are hazily sketched if present at all. Even exhibitions held in Jewish museums around the world do not go as far as this one in exploring and presenting his Jewishness although the curator does single out "Chagall. Love, War and Exile" in 2013 at the Jewish Museum in New York, an exhibition I happened to see. It had a lot of works from his American period, but in essence it was just ‘another Chagall exhibition’ with a little bit from different periods, a kind of generalised Chagall. It was Chagall without crucifixes, which occupy a separate place in his work and only here, at the Schirn exhibition is their actual meaning revealed. They are not to be seen as a concession to Christianity rather a Jewish sacrifice – and just one of many. Jesus, with a box of tefillin on his forehead and his loins wrapped in talis, is a perfect illustration of what was going on in Europe. And what the artist was hearing about while he was living at a distance in America and from where he could not help anyone.

We witness Chagall searching for the means that would allow him to capture traces of Jewishness. Jerusalem seen in 1931 – live, not in his dreams. And in 1935 the Great Synagogue of Vilno which was later destroyed by the war. Marc and Bella Chagall arrived in Vilnius at the invitation of the Jewish Scientific Institute conference, and although it was a mere 350km to Vitebsk they were not allowed to go there. In Vilnius, a mob beat up the famous Jewish historian Semyon Dubnov, then a 75 year old man in front of their eyes. In the summer of 1937, shortly after they finally received French citizenship, Chagall's works were hung at the exhibition of degenerate art in Munich. The space for freedom was shrinking, especially for Jews, although Chagall managed to escape from Vichy France. He managed to escape because he remembered the cardinal rule of Jewish security: pack your stuff and run for your life. He did not manage to save everyone. His people, his milieu, the Yiddishkite celebrated by Chagall, had ceased to exist. And this was for Chagall a loss no less tragic than his loss of Bella, who died in 1944 and remained in New York forever. A victim of the "World in Turmoil", which began to disintegrate in the 1930s and 1940s and once more is in a state of disintegration.

Chagall. World in Turmoil

Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany

4 November, 2022 – 19 February, 2023