Video Art in Russia as Philosophy in Motion

PROVMYZA. Gerund. Exhibition view. St. Petersburg, 2025. Photo by Ivan Sorokin. Courtesy of MYTH Gallery

The exhibition of artist duo PROVMYZA from Nizhny Novgorod, known for their epic, though-provoking videos, is now on view at St Myth Gallery in St Petersburg. Yet there are many more creatives on the scene who use this medium to deliver complex messages through symbols and allegories. Curator and art critic Antonio Geusa reflects on the evolution of artists whose videos are more than meets the eye.

In the mid 1960s the arrival of video equipment in electronics stores across the USA, Japan, and much of Western Europe sparked off what some called a revolution in the art world. Marshall McLuhan’s famous equation ‘The medium is the message’ (a modern adaptation of Lenin’s order to the Bolsheviks “Seize the telegraph!”) meant that those who control the channels of mass communication control the message, and ultimately, the masses. Portable video technology enabled people to build an alternative distribution information network for the mainstream mass media that could undermine the economic and political forces in power. It could break with tradition, preaching the importance of process over the product, the active role of the audience in the fruition of art, and the need for artworks that open the eyes of the viewers instead of anesthetizing their minds in view of the commodification of beauty.

Video art was born with a mission.

In Russia, the first artist’s video was made exactly twenty years after Nam June Paik (1932–2006) showed his tape of a traffic jam at New York’s Cafe ‘Au Go Go’ (1965) recognized as the start of video as an artistic practice. While Paik had the financial support of a grant, Russian video art began without the artist even owning a video camera or recorder. In 1985, with the help of Sabine Hänsgen (b. 1955), a West German PhD student researching Moscow’s underground literary scene who had brought a VHS video camera to Moscow, Andrey Monastytsky (b. 1949) recorded ‘Conversation with a Lamp’ in his studio, “a performance for the video camera”. Fittingly and surprisingly, Russian video art starts with an elegy to the effects of a video camera in the art-making process. Sitting shirtless with a lamp between his legs, Monastyrsky is scared because he feels that the “video eye” forces him to prove that he is an artist. He does so with a 25-minute monologue in which he reflects on Moscow Conceptualism, recites his 1975 poem ‘I Hear Sounds’, and draws a grotesque face on his chest starting with two black dots representing the 19th century Russian poets Afanassy Fet and Fyodor Tyutchev.

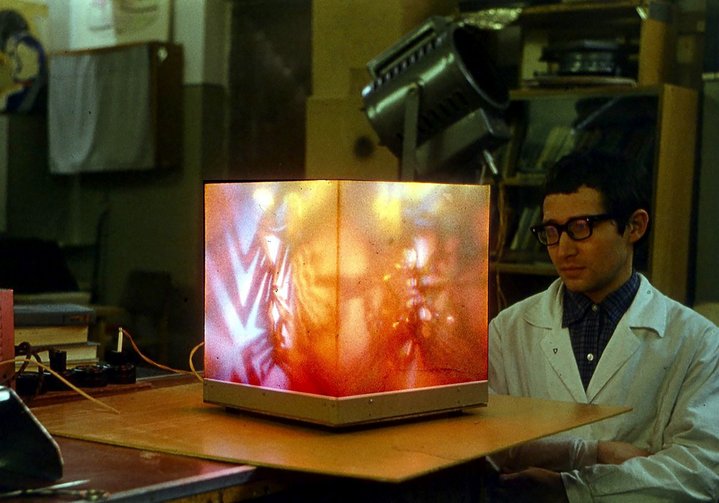

Video entered the Russian art scene on tiptoes, without grand declarations of war against the information manipulation from the Soviet politburo, or any belief in the subversive power of art at the ballot box. It is telling that Andrey Monastyrsky did not even keep a copy of his work because he did not have a video player. Until the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, video art in Russia developed at a slow pace nurtured by a handful of pioneers in Moscow, Leningrad, and Kazan. It was in Kazan that, through the work of the Prometheus collective led by Bulat Galeev (1940–2009), video art was shown to a wider public for the first time, and the first video installations were made. Together with the production of single-channel videos based on their approach to synesthesia and inspired by the notion of “All-Unity” conceived by composer Aleksandr Scriabin (1872–1915) they developed a form of language that was rather unsophisticated and too direct for an audience with very little familiarity with media art (and contemporary art practices in general). In Leningrad Pirate Television operated from 1989 till 1992, a “TV station” that never actually broadcast anything. Instead, it recorded on tape a series of wild, irreverent, flamboyant shows, often bordering on camp, reflecting the spirit of perestroika and the growing need for self-expression beyond the limitation of the Soviet standards of ‘proper behavior’. Tellingly, no master copies were made or archives kept. Ironically, what has survived today are pirate copies of those “TV programs”.

This pioneering period was also characterized by the almost total absence of critical analyses of what was made on video. The exception was Boris Yukhananov (b. 1957), an artist who created a cycle of “video-films” grouped under the title of “Crazy Prince”, who contextualized his theatrical experiments within the microsystem of Parallel Cinema (Soviet underground cinema). He developed on tape a new form of cinema, called ‘slow video’, made using the inner qualities of the technology, such as the ability to record both images and sounds on the same support and the reusability of the tape.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia’s art scene transformed with the arrival of commercial galleries and state institutions who began to exhibit contemporary art. Yet, video art remained on the periphery until the late 1990s. In early exhibitions, video was often a minor element within larger projects that included painting, sculpture, drawing, and photography. Unlike ‘mainstream’ contemporary art, which enjoyed the interest of the newborn market, video art remained an experimental field, occasionally crossing into unconventional places like nightclubs.

In the period just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, video was still seen as a novelty without much history, as pre-1991 works were largely unknown. Recognizing this gap, several cultural centres – most notably TV Gallery in Moscow – began screening international video art programs with the help of foreign cultural institutions. However, in just a decade, both the production and fruition of video art grew exponentially all over the vast territory of the Russian Federation, cementing its importance in the popularization of contemporary art practices and, importantly, favouring the international recognition of quite a few artists. By the mid-2000s, Russian video consisted of a plethora of different voices and intentions, each one with its own philosophical approach. In the 2000s there emerged three artist groups and one individual artist who for different reasons stand out as being of exceptional importance in the history of the medium of video art in Russia.

PROVMYZA’s slow-paced, stripped-down aesthetic stands in stark contrast to the simple and raw style of early Russian video art. Founded in 1998 by Galina Myznikova (b. 1968) and Sergey Provorov (b. 1970), the duo is renowned for its meticulous visual control and profound exploration of existential themes such as isolation, alienation, fear, internal conflict, emotional paralysis, and human vulnerability. With dreamlike visuals and carefully crafted compositions, their videos evoke a sense of disorientation, drawing on elements of experimental theater and contemporary dance, with sound playing a key role in heightening emotional impact. Their open-ended narratives invite viewers to reflect on the complexities of modern life, exploring how it disconnects people from their emotions and raises questions about complicity and responsibility in the face of chaos. These works often depict ambiguous situations of control and submission, mirroring a world on the edge of collapse and suggesting the inevitability of repeating past traumas in the search for resolution – a poignant reflection on today’s troubled times.

Based in Nizhny Novgorod, PROVMYZA has helped decentralize the Russian contemporary art scene, proving that it is possible to create internationally recognized art outside of Russia’s traditional cultural capitals and inspiring artists from other regions to pursue ambitious projects without relocating to Moscow or St. Petersburg.

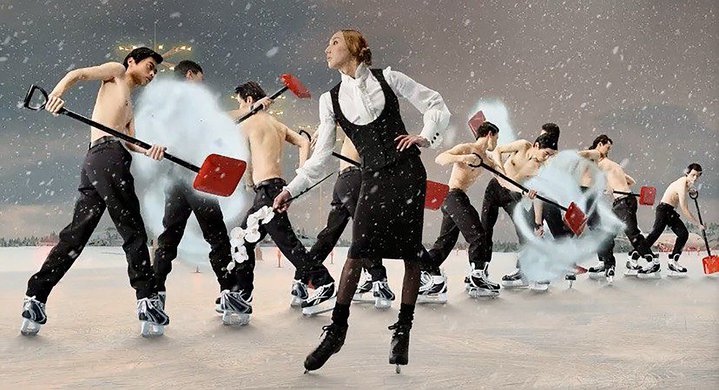

AES+F, founded in 1987 by Tatiana Arzamasova (b. 1955), Lev Evzovich (b. 1958), and Evgeny Svyatsky (b. 1957), with Vladimir Fridkes (b. 1956) joining in 1995, is a collective known for its strikingly surreal, hyper-real visual style that merges classical references – such as Renaissance and Baroque compositions – with contemporary imagery drawn from fashion photography, advertising, and video game aesthetics. This fusion results in a futuristic, nevertheless deeply allegorical, aesthetic that reflects the moral ambiguities of contemporary consumer society. Their captivating and conceptually rich videos (and monumental, multi-channel video installations) address themes such as globalization, consumerism, violence, and the clash of civilizations, exploring the tension between utopia and dystopia. War, death, desire, and the collapse of civilization are recurring motifs, yet these subjects are depicted in a surreal, almost seductive manner, blurring the line between beauty and horror.

The Blue Soup group (Daniil Lebedev (b. 1974), Aleksey Dobrov (b. 1975), and Valery Patkonen (b. 1972) was founded in 1996, and later in 2002, this trio were joined by Aleksandr Lobanov (b. 1975) – whilst Patkonen left in 2010. It is a collective renowned for creating visual and audio experiences that blend theatricality, irony, and conceptual depth, making their art both easily accessible and thought-provoking. A distinctive feature of their work is an approach that often results in seemingly strange, nonsensical, or absurd situations. While their work on the surface is rarely overtly political, it subtly critiques power structures, societal norms, and cultural stereotypes. The Blue Soup’s aesthetic leans toward a kind of visual poetry that favors minimal, simple, and recognizable structures that prompt viewers to search for deeper meaning. Their storytelling is typically fragmented and nonlinear, evoking the complexities of human memory, perception, and the absence of clear meaning.

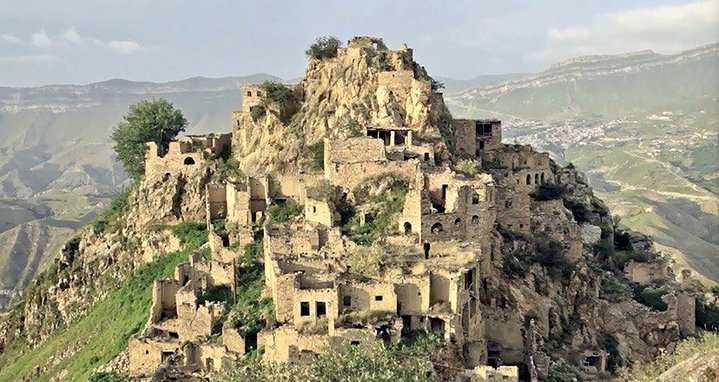

Working independently, Taus Makhacheva (b. 1983) delves into themes of identity, cultural heritage, tradition, and the political implications of contemporary life, with a particular focus on her Dagestani roots and the complexities of self-identity in post-Soviet Russia. Her art often uses humour and absurdity to address serious issues, employing these tools to challenge norms while making her work accessible and inviting critical engagement.

A central element of Makhacheva’s practice is the human body, especially in relation to gender and cultural expectations. In some pieces, she uses her own body to perform physically demanding tasks in order to challenge perceptions of gender and strength while offering a commentary on how these intersect with cultural roles. Very often, her work draws on the rich cultural heritage of the North Caucasus, blending it with reflections on contemporary Russian life and global influences. In doing so, Makhacheva creates a personal mythology that reinterprets geographic narratives, cultural heritage, and historical events, transforming them into a lesson for understanding the present…for those who want to learn.