Sergei Shutov: the father of Russian video art

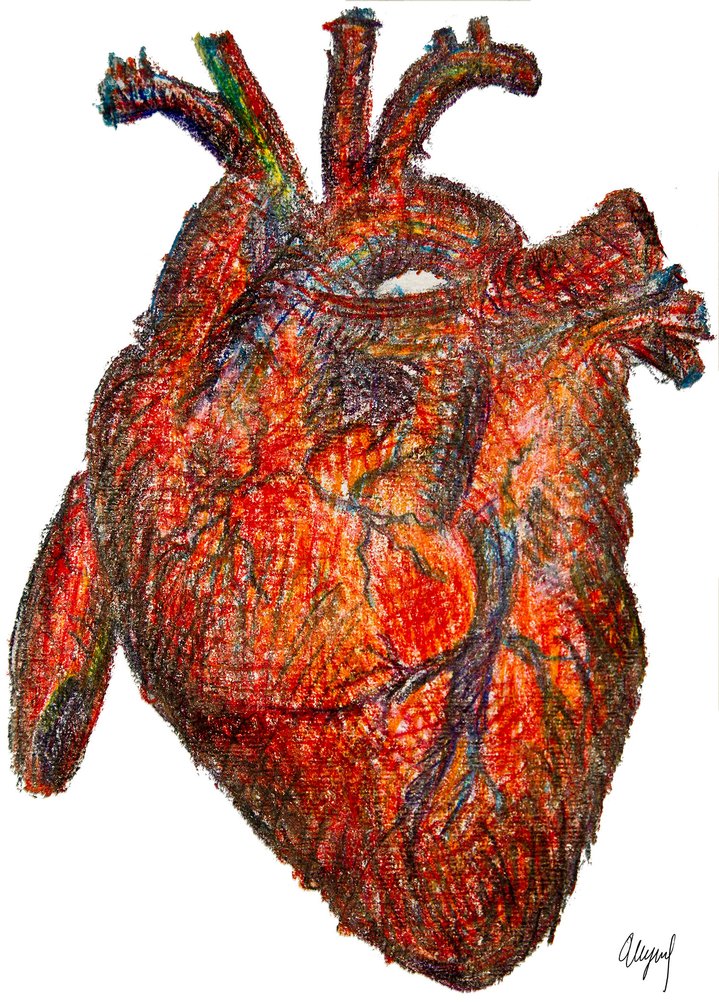

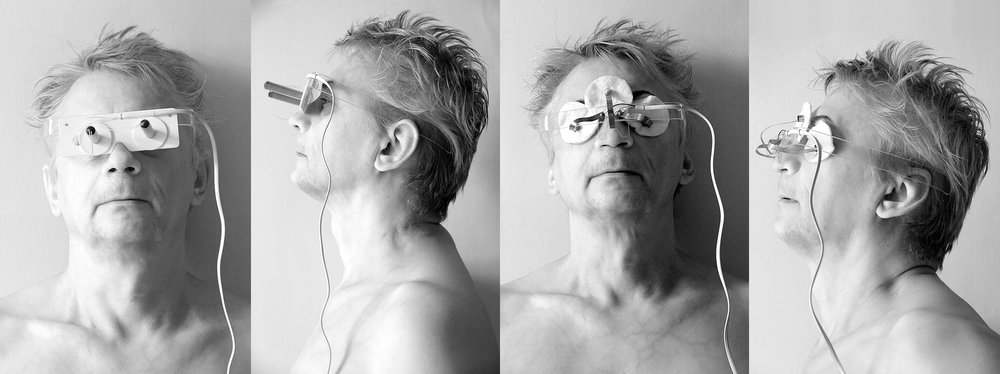

Sergei Shutov. Phosphenes and we, 2011.

MAMM museum in Moscow is honouring Sergei Shutov, the man who paved the path for video and new media artists in Russia and beyond. His retrospective exhibition is open until November 15.

December 1991. The Soviet Union collapsed marking the end of an obsession imposed by the state that the only way forward was for art which was socialist in content and realistic in form. Contemporary art practices that had hitherto not conformed to the canons of Socialist Realism left the underground almost overnight, where they had been relegated for decades. Russian contemporary art surfaced and met the wider public for the first time while rock music and the euphoric chaos of the New – new flags, new anthems, new banknotes, new names for streets and state organizations – were playing in the background. Moreover, new technologies employing videos and making use of computer hardware were introduced as a means of artistic expression. It was around this time that Russian video art was born. But who was its father?

The answer comes with a clarification. Sergei Shutov (b. 1955) is the father of Russian video art. He is not its biological father – as far as history is concerned, the very first piece of video art was made by Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949) in 1985 – but he was the one who nurtured the newborn and helped it to walk. In the early 1990s, Sergei Shutov spent a great deal of time and energy carrying out his own experiments and creating his own works in this medium, as well as helping numerous artists, both established and emerging, to make their first video works. He was also the driving force behind a series of projects, such as large-scale exhibitions and festivals of media art in Russia. One example is the Art Technology Institute (ITI) that he founded in Moscow in July of 1992, whose importance lies in the fact that it was the very first educational institution to provide artists with a “working space and access to the hardware needed to proficiently develop the necessary skills”.

As an artist, Shutov’s videography of the 1990s is deeply rooted in the so called ‘klubnaya kultura’ (“club culture”) of the time. In fact, discos and raves were new in post-Soviet Russia, where people from different generations would gather together in need of a place with things that were new and bold and had been previously forbidden or strongly repressed. The use of computers and editing software in the making of these ‘psychedelic videos’ are of fundamental importance. They are full of digitally generated effects, such as rapidly rotating shapes, quick alternations of brightly coloured backgrounds, 3-D modeled figures, multiple exposures and digitally modified excerpts taken from Soviet cult films. Quite interestingly, although the club is no longer the hub of freedom it was in the 1990s and ‘klubnaya kultura’ is no longer bonded together with contemporary art, Shutov’s videos from those years have found new popularity amongst today’s public as proved by Shutov’s retrospective exhibition ‘Strangers Don't Walk Here’, which is currently on view at the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow.

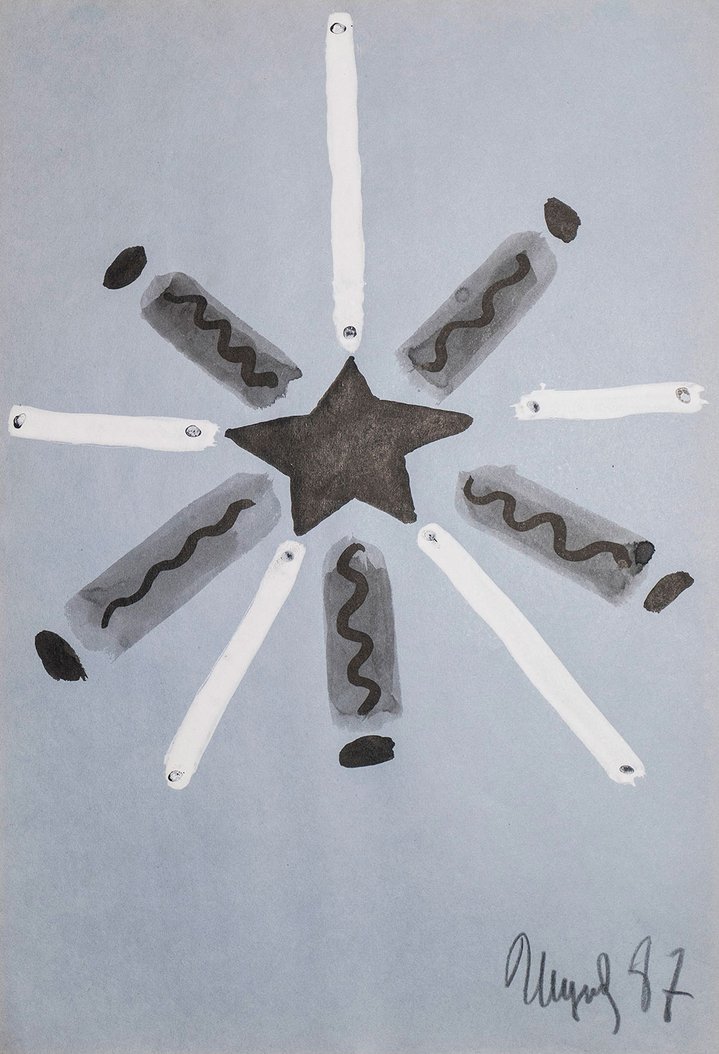

Without denying the place of Sergei Shutov in the history of Russian media art, it would be reductive to confine its practice in the territory of art made with new technologies. Moreover, it would be quite difficult to determine which one is the medium that better defines Shutov as an artist. His practice over the years spans a wide range of media and techniques. The themes his work touch on and the stories they tell are often rather diverse – the artist likes to recount that he made his very first work of art when he was a third grade student in the first half of the 1960s: a science art installation about the adventures of oceanographers who studied the language of dolphins, which used projections and sound. It appears evident, however, that Soviet science fiction and popular science magazines from the 1960s and 1970s had a great influence, especially on his paintings and installations. In particular, the conquest of outer space is the background in many of his works. This fascination for the cosmos goes beyond the pride of achieving the impossible and a faith into a brighter future that a whole generation had felt. Importantly, the space race that took up a great deal of time and resources of the Soviet government becomes symbolic of the paradoxes which characterized the way power controls people’s lives in Shutov’s works. In fact, the barbed wire that the artist uses to make his cosmic vehicles, stars and planets is a reminder of the fact that the very first flight of a man into outer space was the result of the work of scientists deprived of their freedom and locked into prison camps.

History has its generals. Without a doubt, Shutov has always fought in the front line and helped to win a few battles in the war for the acceptance and inclusion of contemporary art in Russian cultural processes. He is an artist who has already managed to play many roles and has taken part in most of the events that mark the course of Russian contemporary art history in both Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Furthermore, his rich biography proves that he is more than an artist. He is also a writer, a musician, a DJ and a video-Jay, a curator, a director of an art institution, an actor, a set designer (he made the sets for Sergei Solovyev’s iconic film ‘ASSA’ (1987), as well as – quite a rarity in Russian art – an engineer: for the Ptyuch Club in Moscow, in the mid-1990s, Shutov built a network of computers, mixers and VHS recorders that allowed the simultaneous transmission of sound from vinyl records and images from VHS tapes to about thirty television monitors spread throughout the premises. Maybe, the whole body of what he has done so far could be seen as an assemblage of tracks, just like the album ‘Shutov Assembly’ that musician Brian Eno released in 1992 and dedicated to Sergei Shutov as a token of gratitude after the artist had given him one of his paintings as a present when they met in Moscow. Many different tracks, each with its own story and mood.

Sergei Shutov. Strangers Don’t Walk Here

Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow (MAMM)

Moscow, Russia

September 4 – November 15, 2021