Mikhail Roginsky. Asceticism and Humility as a Brand

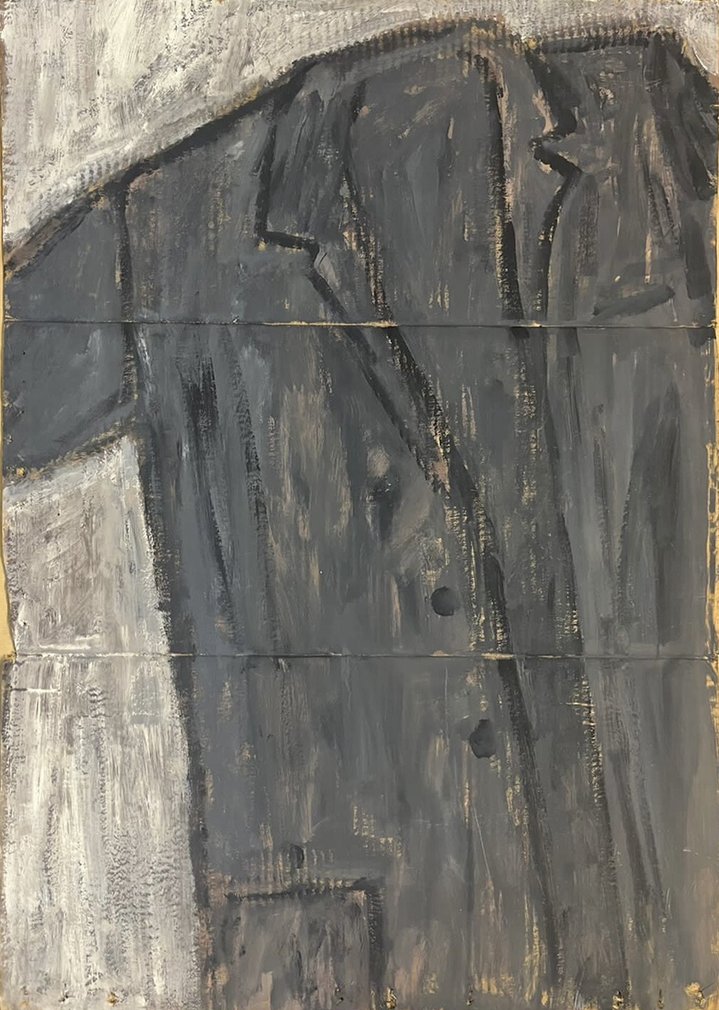

Mikhail Roginsky. In the courtyard, 2002. Courtesy Vellum Gallery

Two leading Moscow galleries, Vellum and pop/off/art, are exhibiting late career works by Mikhail Roginsky, a classic of Soviet unofficial art.

These two shows force us to reflect on the changing fortunes of a modest artist. After he emigrated in 1978, Roginsky fell into compete obscurity and struggled to make a living by selling his paintings to Parisian gallerists. Today his legacy is a highly prized asset, the object of shenanigans and criminal manipulations in the Russian art market.

Mikhail Roginsky (1931–2004) did not like art. For him autonomous creativity, when aimed at creating masterpieces, is a kind of narcissism, both pretentious and false. Instead, he chose to paint deliberately unaesthetic, banal, humble subjects taken from everyday life which became his credo. His manifesto is ‘The Red Door’ which exists in several versions, the first made in 1965, formerly in the collection of Leonid Talochkin. When you look at Roginsky’s door, you realize what he was close to and what was alien to him in ‘ready-mades’ and ‘pop art’. He chose a thing in its most artless sense and presented it as an art object. However, this object did not turn out to be, as in American Pop Art, an apology for the impersonality, circulation, and consumerist ´marketability´ of the object. On the contrary, the unique rough, worn surface of the door with subtle gradations of relief and shades of colour turns out to be a narrator of a certain personal biography of the interior of the object. It makes us think about the vicissitudes of its life in flats and workshops, about the change of owners, about those with whom it exchanged handshakes. In other words, Roginsky is not an adherent of consumption and circulation, but a chronicler of the memory of things that are simple and everyday yet carry complex existential meanings.

The curators have come up with two very different shows. At Vellum, curator Lyubov Agafonova, together with scenographer Andrei Klimov (b. 1968) and performance artist Andrei Bartenev (b. 1965), have created a kind of total installation. They have enhanced his still lifes of teapots and gas cookers, worn shirts, brushes and bottles with real objects, including cut glasses, cookers and teapots. And Bartenev added some futuristic spacesuits in homage to Roginsky's paintings of rippling human masses in the Moscow metro.

On the contrary, At pop/off/art, the exhibition is quite ascetic. Spread out on the long walls, are a dozen paintings on the theme of memories of pre-Perestroika Moscow when he painted during emigration in Paris.

Both exhibitions are interesting and on reflection you might even conclude that Roginsky’s apologia for the memory of simple objects makes him a romantic. Contrary to his radical declarations of anti-art, he is rather a disciple of the kind of colourful themes you see in the work of Chardin, Rozanova, Kiefer and Baselitz. The exhibition at the Vellum Gallery includes many still lifes made in his last years. Shelves with bottles are painted in an unsophisticated way using a deliberately poor technique: acrylic on packing cardboard or paper. Yet the carelessness of execution is only apparent: with his brush the artist probes the coordinates of compositional gravity, all the ratios of verticals, horizontals and diagonals. He creates a colour image with open strokes of paint, precisely defining the volume and depth of space. Today, all this alleged sloppiness is read by the eye as aristocratism of the highest kind, born easily, improvisational, impromptu. And every object, be it an old coat or a gas cooker with tongues of blue flame around the burners, somehow calls to mind the theatre of suffering things by Christian Boltanski (1944–2021), or Jannis Kounellis (1936–2017), the representative of the Arte Povera movement.

Roginsky did not like the classical picture form. His compositions are often careless, the subject environment and urban banal scenes with grey people on the street are executed in a naive, underlined ‘wrong’ in their manner of composition. The artist turned to the most unartistic of materials like corrugated cardboard. He painted with oil, acrylic, or whatever he had at hand. However, the subtle gradations of light and colour help to experience a heuristic feeling, akin to communicating with the paintings of Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964), another fierce defender of naiveté and primitivism of the early 20th century.

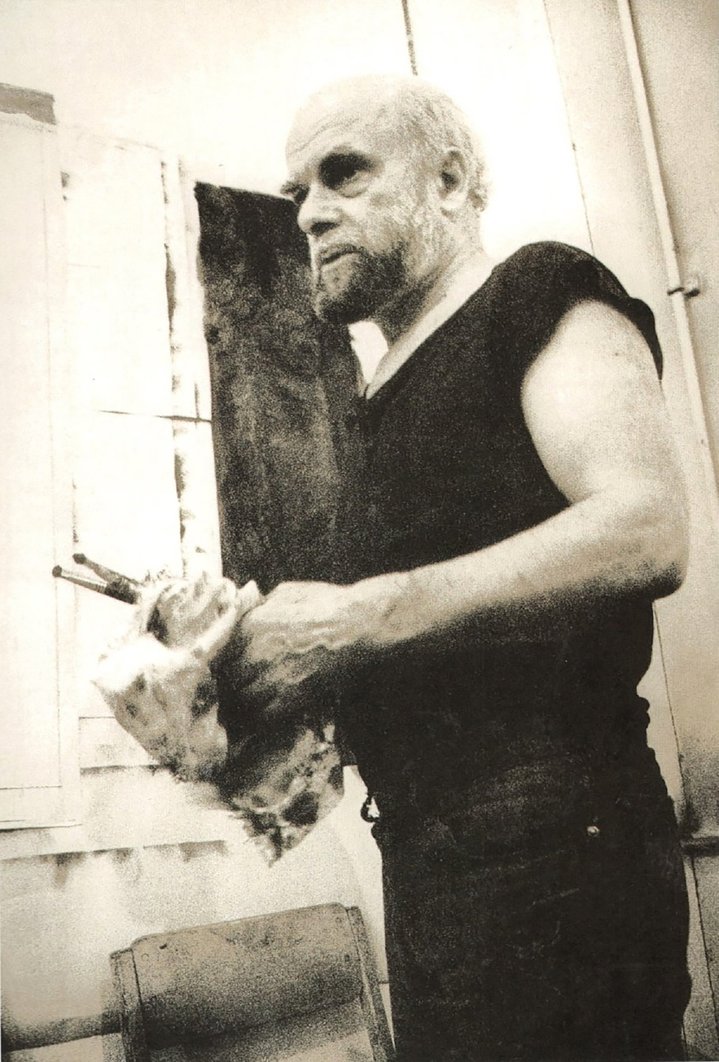

Mikhail Roginsky, who defended the sincerity and artlessness of the simple life in his art, was also an aristocratic ascetic in his everyday life. He did not understand the laws of the art market. Having moved to Paris in 1978, he did not make a career for himself. He painted a lot of paintings on all sorts of rubbish materials. He often gave them away. In Paris he was not charmed by the beauty of boulevards, Versailles or the Louvre, but with manic persistence painted from memory views of unsightly Soviet Moscow with its shabby fences, cars and sullen queues. Works from this Moscow-Paris series are exhibited in the pop/off/art gallery.

The paradox is that the legacy of this selfless ascetic-aristocrat had a different fate. Collectors are now swarming around Roginsky's ‘anti-art’. The artist's widow Liana Shelia-Roginskaya made a big attempt to bring some order to her late husband’s artistic heritage which had been scattered among many different collections. She set up the Roginsky Foundation with support from the InArtibus Foundation, founded by Inna Bazhenova. In 2014 they staged the largest monographic survey of his work, at Ca Foscari in Venice, comprising 120 paintings, ‘On the Other Side of the Red Door’. The show was curated by Elena Rudenko. The exhibition which formed a kind of chronicle of the artist’s life was designed by Eugene Asse, a beautiful installation of Roginsky’s works in the palazzo’s interiors, wall colours echoing the palette of his paintings.

Sadly, since Liana Roginsky passed away in 2022, her valuable work on Roginsky’s huge and unruly legacy suddenly ground to a halt. Since then, there has been infighting between galleries who are struggling to control prices and sales; ownership issues; problems of attributions; there are fakes, and question marks over the integrity and preservation of the artist’s archive. Today it seems that the commercial odyssey of the works of this non-commercial artist is entering a new phase, and these two concurrent shows in Moscow demonstrate just that.

Mikhail Roginsky’s Coat

Moscow, Russia

13 February – 21 April 2024

Mikhail Roginsky. Moscow, Gorky st.

Moscow, Russia

17 February – 20 April 2024