The tolerable talent of Boris Kocheishvili

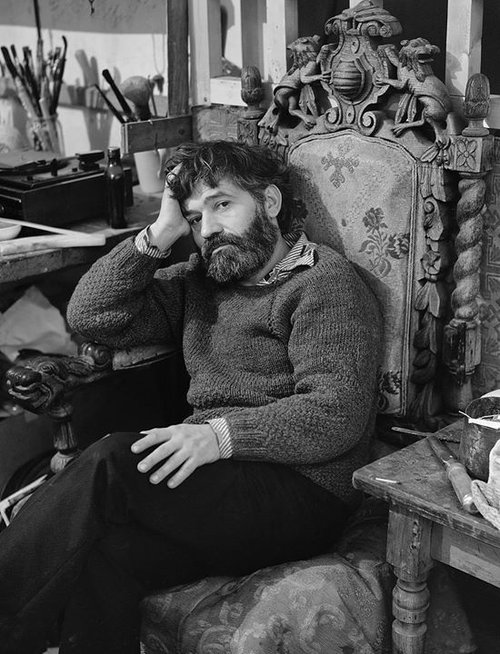

This octogenarian artist and poet, who has shied away from the limelight for many decades, is finally showing his work to the public on a large scale: in Moscow there are two solo exhibitions running in parallel.

Humility is pervasive of Boris Kocheishvili (b.1940), both his persona and his works, which are at once so varied – oil paintings, ink drawings, plaster reliefs, poetry – and undeniably part of a continuous whole. It seems uncharacteristic for an artist today where there is a constant jostling for attention in streams of exhibitions, press and social media. Kocheishvili professes to be indifferent to popularity: “I never thought or think about any kind of viewer, apart from myself perhaps.” This self-sufficiency is also a quiet confidence, without the need for external approval.

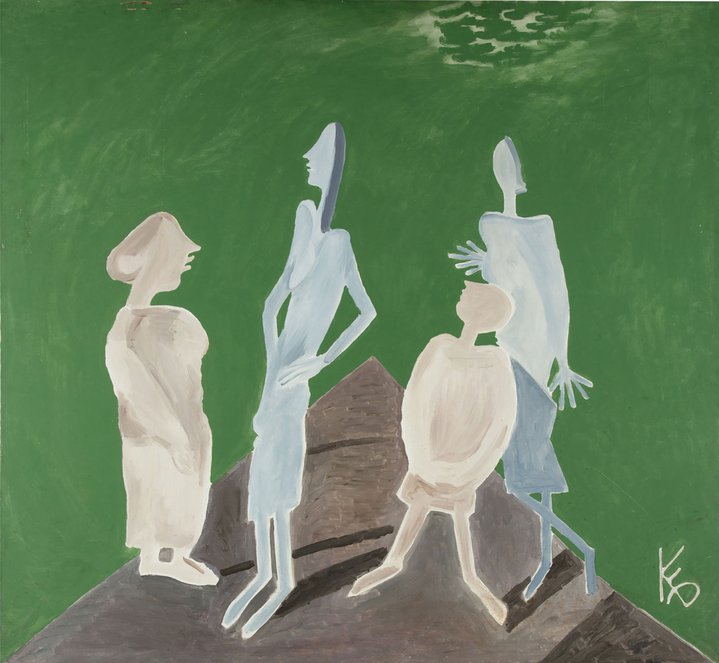

Perhaps for this reason, Kocheishvili is not as widely known as might be expected for an artist of his standing – he never sought out the limelight. At the same time, critics who have tried to analyse Kocheishvili’s art find it difficult to grasp a concrete plot, or “concept” that could be easily pigeonholed. A stylistic contextualisation might position him between Picasso, metaphysical painting, the Russian avant-garde, or the Soviet nonconformists, for example, but this superficial analysis is not so helpful when we want to simply enjoy the artist on his own terms.

His formal art education began at the Moscow Academic Art School (MAKhU). After graduating, he became the youngest member of the Union of Artists and this earned him a research trip to Italy. Coming from the Soviet Union, this was a rare undertaking. Was this a formative trip for the young artist? “No,” he says, “I never waited for someone to educate me, I educated myself as soon as I started drawing. Great artists are no role models.”

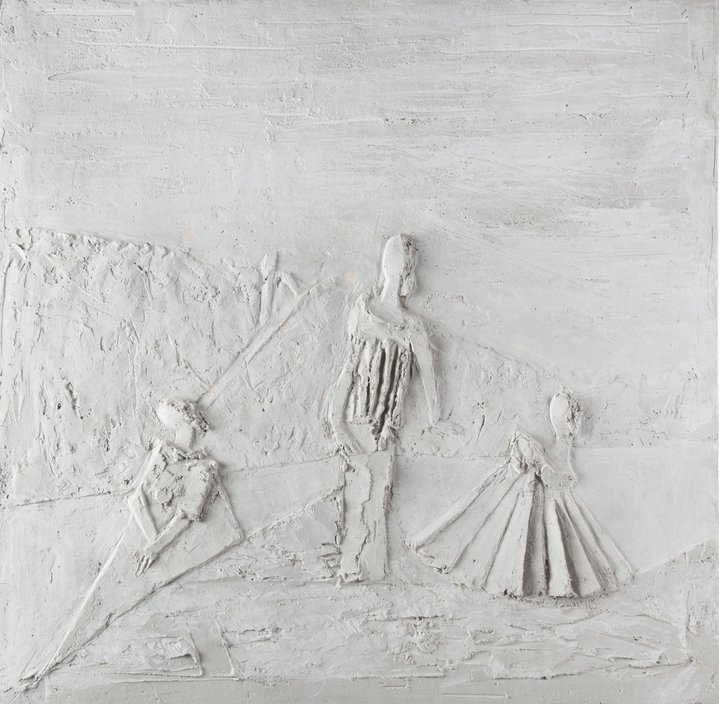

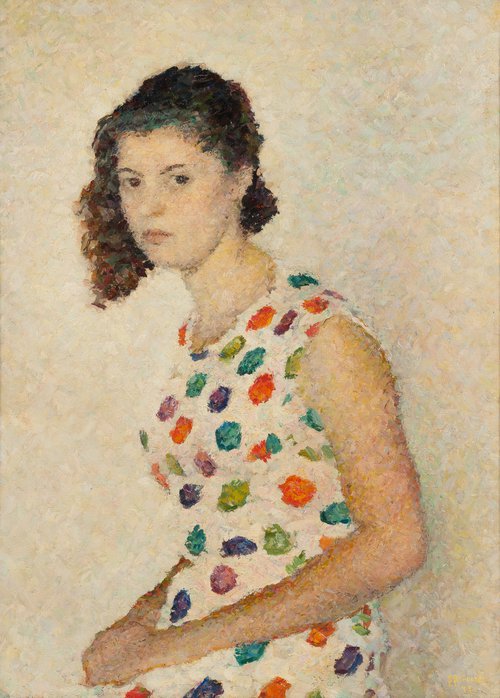

More formative were the friendships and connections he made in Moscow. His first marriage was to Ksenia Kupetsio, who came from an artistic family belonging to the so-called ‘Intelligentsia’. He joined the legendary Nivinsky printing studio headed by artist Evgenii Teis (1900–1981) and he moved in circles with famous underground poets and artists. His second wife was eminent actress Liya Akhedzhakova – and the theatre became a leitmotif in Kocheishvili’s paintings, where staged characters sit in semi-fabricated sets. But, his friendship with sculptor Adelaida Pologova (1923–2008) was most formative by his own admission “in terms of aesthetics, ethics, and practicalities”. Spending time in her studio observing her at work, he expressed a regret that he himself hadn’t become a sculptor. She encouraged him to experiment with reliefs, which would combine his drawing skills with a sculptural element. He followed her advice, in what was a new chapter for him and, later, became his trademark. He speaks of how reliefs are a rare genre in contemporary art likening them to cave paintings.

In a 2013 essay, he wrote, “Art is directly related to the representation of people, reflecting their biology, physicality, motor skills, psyche and so on. So, it turns out that from cave painting to Picasso, the quality and essence of art have not changed.”

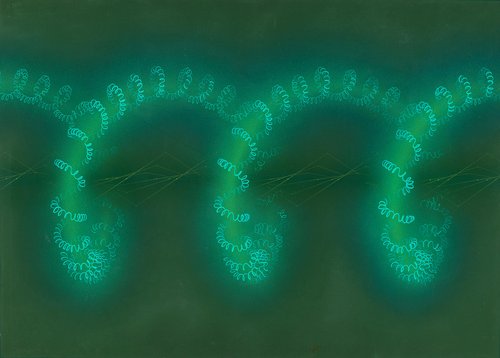

There is something primal in his schematic figures, reduced to a bare minimum they are characters, the people like letters and words. Kocheishvili’s works seem to come from a place where text and image are one and the same – it is mark-making, they are signs that carry meaning. Abstraction and realism are inseparable also, because, although a product of his imagination, his world is on some level a real one and his artworks become objects in the real world, boundaries become blurred or maybe you cannot even apply them. Something of the magic of cave painting is present, where images are cyphers for deeper meanings, lost in time, but open to interpretation.

Kocheishvili is by no means a caveman — he is deeply educated and cultured — however, he reserves an admiration for hermits, with their non-reliance on society and the ability to be self-sufficient. In the 1990s, Kocheishvili locked up his Moscow studio and moved away to a village in the countryside for years, where he stopped painting and decided to write poetry. He was searching for a kind of chastity he says, in his escape from the city crowd.

This autumn, two solo exhibitions are running simultaneously in Moscow, one at the State Tretyakov Gallery titled ‘Boris Kocheishvili. Me and THEM’ (November 12 – January 9, 2022) and a smaller show titled ‘Me and Them. Three Sisters’ (October 28 – December 5, 2021) at the Stanislavsky House Museum.

True to form, the artist has distanced himself from these public shows, entrusting the organisation to his long-time curator Tamara Vehova. “If a work is at all worthy, however you display it – even upside-down, it will be good… Works should be able to stand up for themselves.” Throughout his life, Kocheishvili has continually destroyed his art and poetry by burning it in his fireplace, in a bid that nothing sub-standard should slip through: “Better I select them than someone later on will see them and say – aha, he’s not as good as we thought!”

so what

can I do

nothing, really

two-three tolerable

thoughts

three-four tolerable

lines

five-six tolerable

word-combinations

six-seven

seven-eight

B. Kocheishvili

translated by Alla Mihalevich and Roald Hoffmann

Boris Kocheishvili. Me and THEM

Moscow, Russia

November 12, 2021 – January 9, 2022

Me and THEM. Three sisters

Stanislavsky House-Museum (Branch of MKhAT museum)

Moscow, Russia

October 27 – December 5, 2021