Kulkov’s Paintings Washed Away by Mud

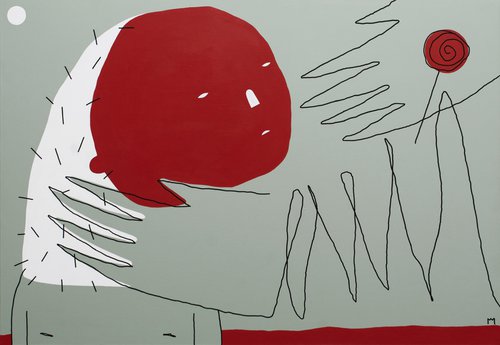

Vlad Kulkov. Rojo, 2023-2024. Courtesy of Vladey

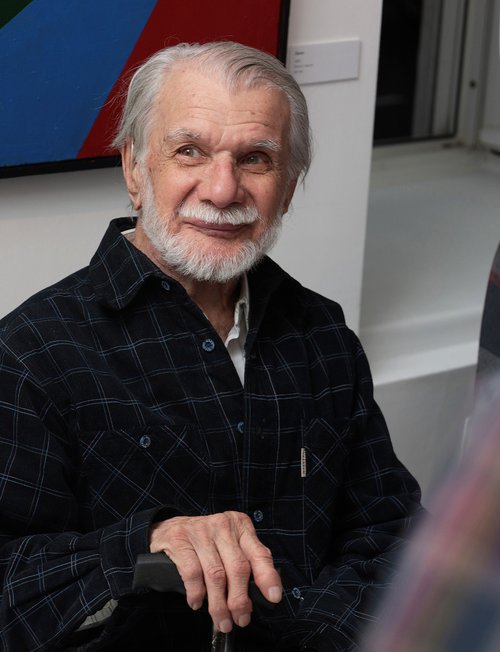

Latvian-born artist Vlad Kulkov who lives today in Tbilisi is searching for the essence of the universe in abstract paintings he has created on a grand scale and are currently on show at Vladey Gallery in Moscow.

Abstract painting today is in wholesale retreat but there are some artists like Vlad Kulkov (b. 1986) for whom it is central to their practice. Born in Liepaiya, Latvia, he discovered his artistic groove in St. Petersburg, graduating from the prestigious Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, an institution that aligns itself with the very best traditions of post-war modernism.

His show at Vladey consists of ten large-scale paintings which seem to vibrate with multiplying multicoloured particles. This series, called ‘Sel’ (‘Mudflow’), represents ongoing explorations into how to depict the essential characteristics of the universe by applying the pulsation of living biomatter onto canvass. The artist literally draws on his knowledge of geology in order to create multilayered images that resemble riverbeds and mountain debris.

These days, it is tough for artists committed to abstractionism. This style is deeply associated with modernism and the unique subjectivity of the artist, a representation of their narcissism and solitude. It is as if abstract art assumes a priori a ‘not for everyone’ theme, one that can divide into the high and the low as well as the visionary and the profane. While this preoccupation with the messianic and the demiurgic was expressed most successfully in American abstract expressionism of the post-war period and in the writings of its main theorist, Clement Greenberg, it later came to be criticized by conceptualists and pop artists of the 1970s. Today, the modernist themes of fetishism of form, visionary concepts, and pathos are no longer appropriate. The illusion of an autonomous work, self-sufficient and requiring the viewer to dissolve into it, were abandoned long ago.

Nowadays, gestures in art cannot but be auto referential. They exceed and destroy traditional boundaries and any claims to exclusivity. The image moves into the space of meta-irony and resonates as a system that is both forming and dismantling before our eyes. Kulkov understands this and, of course, creates works in which criticism of and apology for abstraction are inter-mixed.

It is interesting to compare his works with those of his favourite artist Evgeny Mikhnov-Voitenko (1932-1988), to whom Klukov dedicated his as yet unfinished dissertation. Born in Kherson (Ukraine) Mikhnov-Voitenko is a representative of the unofficial art that emerged in Leningrad during the second half of the last century. Both he and Kulkov are craftsmen who love to use thick colourful mixtures of paint to create tactile impressions while trying to blaze paths up ‘‘into metaphysical heights’’. What also unites them is a shared unwillingness to be held hostage to any one single method or genre. Both are committed to the idea of building a resonant environment in which different methods ranging from expressionism to pop art can co-exist.

However, there are also essential differences between the two. Mikhnov-Voitenko is like an archaeologist as he moves inside the complex layers of colourful substance. He makes pits and cross-sections inside the surface of his paintings. He scratches through the texture, leaving wounds and scars on the surface. These “earthworks”, comprising form, paint and surface, bring him closer to post-war abstraction.

Meanwhile Kulkov shows us paintings that have already been washed away by mudflow. They are much more ghostly and illusory. The artist himself speaks of “washed away images” wanting to somehow visualise the transformations of a collapsing world. His memory no longer holds onto the features of the lost original image.

Kulkov's ‘mudflow’ message suggests a constant slipping away from a deliberately chosen strategy, of adherence to a truly abstract method. His washed-out paintings seem purely hallucinatory, even virtual. They seem to encapsulate both the memory of figuration and the recollection of relief. However, all these memories are projected onto a screen of dancing spectral particles. This quality sparks a constant critical impulse when engaging with his works. Rather than becoming a solitary abstraction, they become openly performative, demanding the active inclusion of the viewer. Free to weave imaginative patterns, one’s gaze can slip through linear arabesques and ripples of colourful flows, a fitting metaposition in line with the challenges of the present.

These challenges abound, in our contemporary world, now such a turbulent place. Kulkov has been a virtual nomad for some time, moving from country to country, living in different continents. From St. Petersburg he travelled frequently to Mexico. He has been living with his family in Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, since 2023. Small wonder that his work is associated with the Brownian motion of continuous movement and the absence of a fixed view of the world.

On the subject of why abstraction is still important today, he replies: “Today's transformations of the world around us evoke a gutteral, heartfelt reaction, a response to individual phenomena and a resonance with the situation as a whole. The series of flashes of violence and disbelief is becoming more and more incomprehensible, but in the depths one can see the movement of the body of civilization awakened by external petty jabs and squabbles. It seems that this swirling mass of cultural layers is indeed gradually realizing the inevitability of transformation, the need to open access to the core, so that all the units of representatives of peoples moving from East to West and back again would be like atomic particles, accelerating and colliding to form a new soul substance.”