Is there a difference between abstract and non-figurative art?

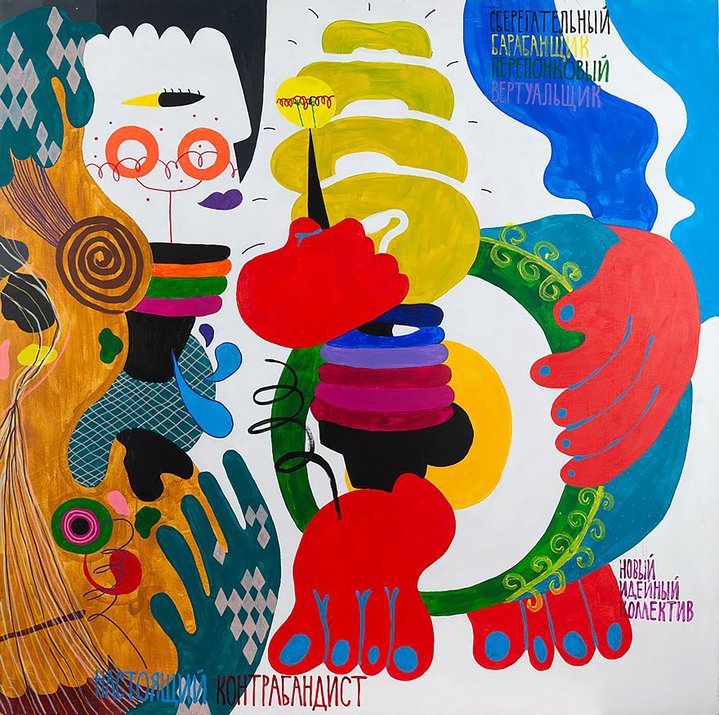

Maxim Svishchev. Cacaphony of the Mind or Decorating the Brain, 2017

The exhibition ‘Accio! Abstraccio’ at St.Petersburg’s Kuryokhin Centre for contemporary art is a brave attempt to draw the lines between abstraction, non-objectivity and non-figurativity. But do these lines actually exist?

The exhibition ‘Accio! Abstraccio’ has opened in St Petersburg at the Sergey Kuryokin Centre for Contemporary Art where it will run until 17th of September. This Centre is named after one of the most charismatic musicians and artists of 80s and 90s Leningrad. Sergey Kuryokhin (1954–1996) was known for his large scale, highly improvised Pop-Mekhanika concert performances, paintings and even occasional cameos in films. The centre was founded in 2004 and since 2010, it has been awarding an eponymous contemporary art prize, the Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Prize, one of the most prestigious and influential in Russia.

The museum has its own collection of contemporary art, however this exhibition includes many works from private collections as well as works given directly by artists. There is a broad range of media on show including paintings, installations, sculptural objects, kinetic sculptures, works made with spray paint, videos, and works that could perhaps best be described as 3D graphics made of metal. The line up includes artists from older generations, such as Elena Gubanova (b.1960) and Ivan Govorkov (b. 1949), as well as millenials. Its concept, according to curator Ksenia Makarenko, is broadly (and tantilisingly) this: a reflection on the boundaries between the abstract, the non-objective and the non-figurative.

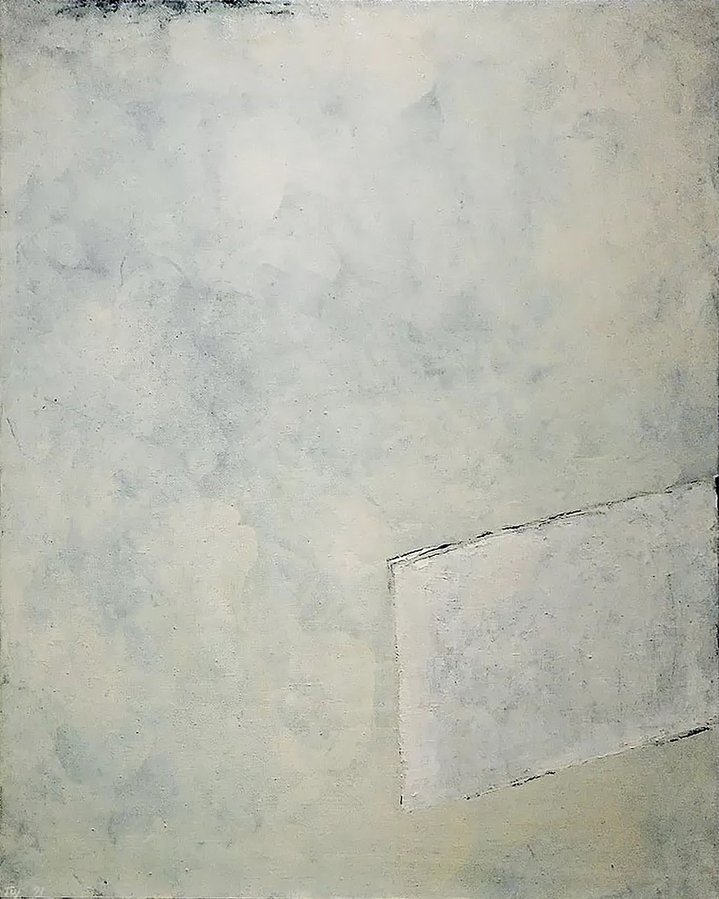

The curator attempts to put across some distinction in the use of these terms through the example of a painting by St Petersburg artist Vitaly Pushnitsky (b. 1967) called 'Sky Window' (1991). This work relates directly to Kazimir Malevich's (1879-1935) programmatic Suprematist work ‘White on white’ (1918). But while Malevich's work is all about monochromatism, limitless space, transcendence and embodies a kind of soaring dynamism, Pushnitsky's work pitches depth, he paints on top of a dark-grey ground that glows from underneath, intensifying the painting’s texture and its materiality. Thus, according to Makarenkova, Malevich's work can be seen as non-objective, while Pushhnitsky's is abstract.

Yet Pushnitsky himself does not see any fundamental differences. When asked about the conceptual boundaries couched in these terms he reasoned: “To my understanding, any two-dimensional work (even a naturalistic one) is a translation into the language of conventional forms and dots, which in our human brains are translated back into 'reality'. So I don’t care about the difference between non-objectivity and abstraction. It's all a flat language of form. I do not argue with Malevich because we live in a different time, and without him our conversation would not have taken place. This is why I respect all monuments of the spirit.”

In another work, Pushnitsky alludes to the iconic ‘Black Square’ (1915). Malevich first turned to this form in 1913 when he created the setting for a futuristic opera ‘Victory Over the Sun’ with music by Mikhail Matyushin (1867–1934) and the text by Alexei Kruchenykh (1886–1968). This unassuming sketch (which became the basis for one of the most iconic paintings in the world) shows a black square at the back of a stage, the diagonal lines sketched out to show volume with the front wall removed. In a 1992 work, ‘Japanese Still Life’, Pushnitsky created a similar theatrical space but covered it entirely in black paint. A small figure in the pose of a lotus, reminiscent of the Buddha, appears sitting beside the abstract structures creating the lines of the stage. Perhaps by finally making this metaphor into something literal, Pushnitsky signals both the beginning of Malevich's creation of form, and its end.

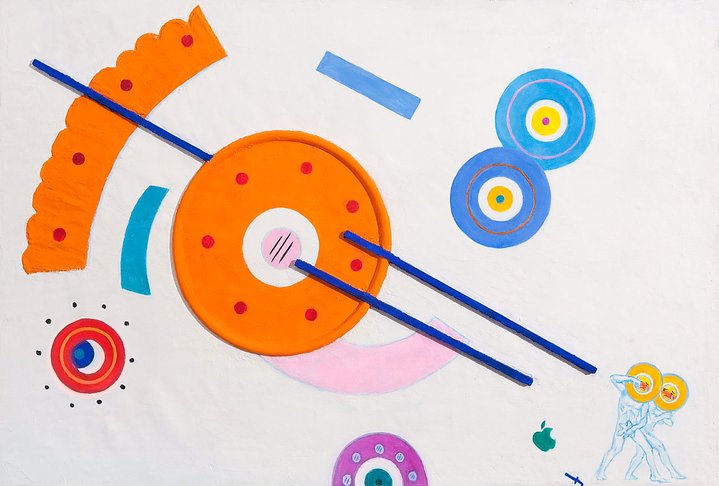

Then there is the image of the Sun. It makes frequent appearances at the exhibition snuffed out, black, distorted, transformed into a sign. We see ‘The Sun’ (1990) by Timur Novikov (1958–2002), the curator calls the artist's characteristic laconic visual formulas ‘road signs’, indicating they can be read instantly. We also see ‘Reflected Sun’ (2005/2013) by Gennady Zubkov (1940–2021), The Black Star (2016) by Sergei Sergeyev (b. 1953), and ‘Space. Landscape with Black Sun’ (1980) by Vladimir Zagorov (b. 1951). The latter work recalls the ‘impressions’ and ‘improvisations’ of artist and theorist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944): it literally flickers between both the figurative and non-figurative.

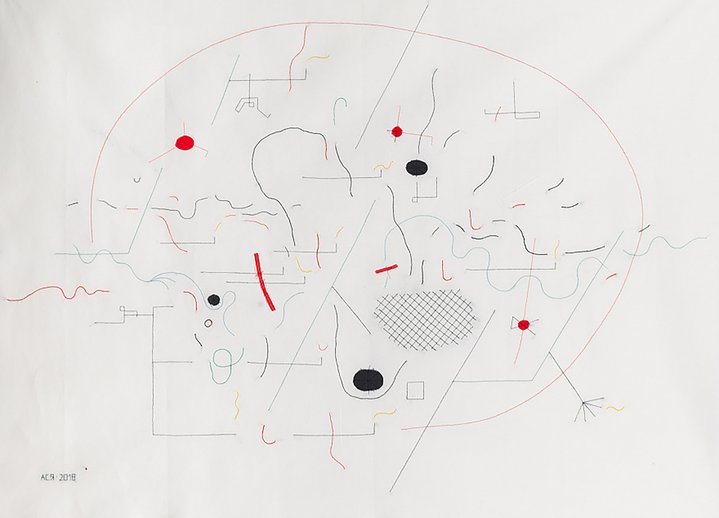

In addition to artists belonging to older generations, the exhibition does include some work by younger established artists. Asya Marakulina (b. 1988), is represented by an ironic and fragile textile work addressing the inner life called ‘Mixed Feelings’ made in 2018. The delicate, embroidered stitching creates dynamic currents spreading out in different directions, creating movement with multiple trajectories, micro events and decisions. The curator draws parallels with a ‘dissected brain’, and its impulses and energies are indeed contained in an oval, like the silhouette of a skull. This reference finds a visual rhyme in the exhibition centre itself as it is placed alongside an enormous sculptural head of Sergei Kuryokhin which was first made for the prize award ceremony in 2019 (the laureates had to enter it to search for their coveted prize figurines). The space inside the head is now used to display videos and sketches for the cover of Kuryokhin's 1993 music album ‘Sparrow Oratorio’.

There is a slightly Magrittean object in the exhibition by Semyon Motolyanets (b.1982), called ‘The Portal’ (heavenly) from 2021, which has many doors, each leading to a dead end. There is an impending sense of vague repetitions and of nightmares which is relieved by the saturated blue colour of the work as well as diagonal lines which create the sense of fast motion. “A portal is like a space that precedes the space itself. There is a door and behind it space does not begin, but is only a prelude to space. (...) I've always been interested in the space between the double doors, the space that remains in the void. There is a whole life going on in that void”, says Motolyanets.

The only work in the exhibition that is perhaps directly linked to the current global political context is ‘Winter’ (2022) by Stas Bags (b. 1984), a graffiti artist who produces paintings and multi-part installations. In a cloudy, cold space we see a monochrome polaroid. It is not obvious at first what you are looking at: a rusty playground, a staircase or a military canon. Nevertheless, the colouring and fragmented composition with an elusive figure creates a feeling of unease. Pixelated square snowflakes are falling from above, resembling the kind of sheets from a calendar which you tear off each day. One of them has the number 24.

Unfortunately the abundance of works by artists of the older generation in the exhibition creates an impression of stagnation. Some of the artists are following in the path of French artist Pierre Soulages (b. 1919) with his exploration of the possibilities of black in the search for inner light (‘outrenoir’), whilst others reinterpret with irony the legacy of Op Artists and Kinetists. There are a number of amusing curatorial ploys for visitors to discover as they wander through the exhibition. Opposite one of the curatorial texts which explains the need to go through, or experience, zero and non-objectivity, there is a 2001 work by Vadim Grigoriev-Bashun (b. 1960) called ‘Transformation through the Black Square’. This work performs a kind of magical suprematist reassembling of the visitors who are to leave the exhibition just a little bit different from how they were when they came in.

Accio! Abstractio

Kuryokhin Centre for Contemporary Art

St. Petersburg, Russia

August 11 – September 17, 2022