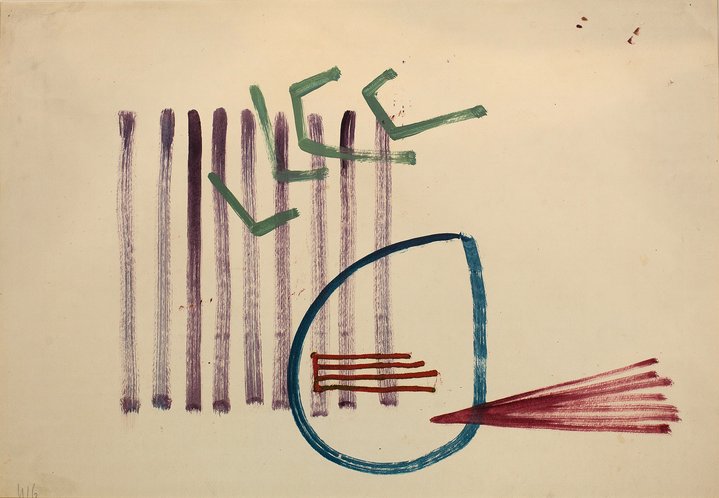

Evgeny Mikhnov-Voitenko. Composition, 1978. Paper, watercolour. 55x76 cm. Courtesy of DiDi Gallery

Evgeny Mikhnov-Voitenko early pioneer of post-war abstraction in the USSR

Works by this little known artist who developed a highly elaborate visual language of non-geometric abstraction as early as the 1950s, are now on view in a compact survey at the DiDi Gallery in St. Petersburg.

Evgeny Mikhnov-Voitenko (1932–1988) is an important figure in Russian art of the latter half of the twentieth century. He was born in the Ukrainian town of Kherson and lived most of his life in Leningrad. As a young man he dabbled in various professions before finding his metier in the production department at the Theatre Institute in 1954 working under Nikolai Akimov (1901–1968). It was to have a big influence on his future path as an artist. Akimov had a taste for metaphysical painting, and ensured his students were exposed to the groundbreaking artistic achievements at the beginning of the twentieth century. Although Russia had been a cradle of the historical avant-garde of the 1910s, for more than two decades after Socialist Realism was established as the official canon 1932, state repression drove free art underground, from where its path back into the public awareness and its struggle for professional recognition began in earnest only in the mid-1950s. In those post-war years Russisan culture went through a fortuitous deja-vu where all artistic styles and phenomena suddenly existed again, simultaneously. Young artists in the 50s and 60s had the feeling of playing catch up, hungering after Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, as well as action painting. In his ideosyncratic art, Mikhnov-Voitenko paid tribute in one way or another to each of these movements.

Co-Existence’ is the name of the exhibition at St Petersburg’s DiDi Gallery which marks the artist's 90th anniversary and is a well-edited, compact presentation of his creative evolution. Following in the footsteps of the early 20th century masters, via the sort of analytical modernist works influenced by Cézanne and Picasso, Mikhnov-Voitenko discovered pure abstraction. The artist freely experimented with a wide range of painting and graphic techniques, working in oil, gouache, tempera, enamel, ink, and felt-tip pens. Starting from 1956 he squeezed oil paint onto canvas and paper directly from tubes for his Tubes series. Today such works may be reminiscent of contemporary artists like Keith Haring or AR Penk, but in reality they stemmed from a personal fascination with ancient cultures and in particular his acquaintance with scientist Yuri Knorozov, who at that time deciphered the Mayan pictographic alphabet. In the 1960s, the artist created large format works in enamel over a metre in size. Expressively splashing the paint, he tried to set the surface of the work on fire in the spirit of Yves Klein’s actions. Mikhnov-Voitenko (a talented musician) often painted with music, mostly Mozart and Bach, playing in the background. Works from the 1980s, such as his ‘Squares’ series, are close to Surrealist automatic writing and are reminiscent of the works of Yves Tanguy. In time, Mikhnov-Voitenko's art increasingly evolved towards a harmonious softness, painterly mastery and a refinement of tone and colour. Late works fully reveal the decorative potential of abstraction; the works are marked by confidence and a kind of Baroque mastery.

As Mikhnov-Voitenko saw it, non-figurative art is first and foremost an area of spiritual insight, and in this, despite all the huge formal differences, he can be compared with Mark Rothko (1903–1970). “I try to understand things, by-passing religious ideas, by creating my own ideas, pictorial ones; and I pray. I pray to paint, to pencils, to paper, any material that supports my feelings.” His diary entries are full of philosophical aphorisms, and between them you sometimes find references to the hardships of daily life typical of artists in the Soviet Union who were not members of official art unions. To earn a living, Mikhnov-Voitenko got a job at the Combine of Painting and Design Art, where he undertook monumental commissions to design public spaces, such as the interiors of the restaurant in the Moskva Hotel with wall panels in crystal and black glass in the technique of free casting, and a chandelier made from a tree trunk with branches.

Artists who were exploring ‘pure form’ in their work during the Soviet years had to overcome the uncompromising resistance of the state and the entire ideological apparatus, which had appointed abstraction as one of its chief opponents. It was abstract painting that stood in for all contemporary art, becoming almost synonymous with it for many years. Wishing to save people from incomprehensible art, the Soviet bosses were not that wrong: abstractionism of the New York school was one of the USA’s cultural exports to Europe as seen in the Venice Biennale in 1950 and the USSR at the American exhibition in Sokolniki in 1959.

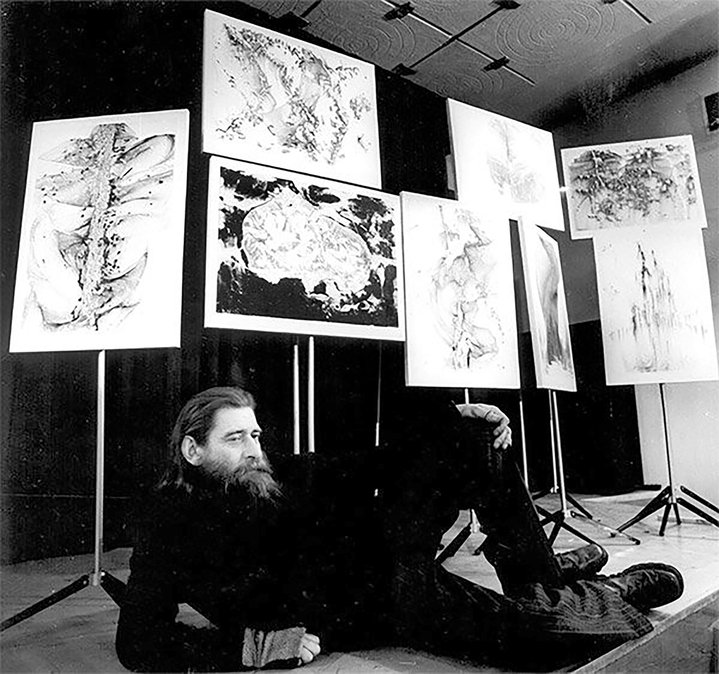

Sadly Mikhnov-Voitenko only had one solo exhibition during his lifetime which took place in Leningrad in January 1978, in a small cinema hall of the Policemen's Club. By that time, the artist, whose individualism and implacable character were well known, had acquired an almost legendary status. Abstract art was particularly popular among the scientific intelligentsia. By holding exhibitions of these artists and buying their works on the premises of their research institutes, inaccessible to the general public, Soviet academics and scientists realised their measure of protest and felt that they were part of the opposition to the Communist regime.

Over the decades, abstraction in the second half of the 20th century as an aesthetic resolution after the collapse of totalitarian regimes, as diverse as that of Willi Baumeister (1889–1955) in Germany, Giuseppe Capogrossi (1900–1972) in Italy, or Wojciech Fangor (1922–2015) in Poland, has been well studied, reassessed and revised many times. These days, the claim of non-figurative art to be a special quest for truth may seem irrelevant and even ridiculous, but it is worth remembering that at the time these works came into existence they played an important role for their creators and their very first viewers.

Over the past fifteen years, little courted by international nor Russian art patrons, Mikhnov-Voitenko’s work has only fetched between $5,000 and $10,000 dollars at major world auctions. In December 2021, a modest auction record for the artist was set at Bonhams Russian auction of £6,375 UK pounds for a large-format work on paper. The art of Mikhnov-Voitenko and several other dedicated abstractionists of his generation, like the Muscovites Yuri Zlotnikov (1930–2016) and Evgeny Chubarov (1933–2012) and the Leningrad artists Mikhail Kulakov (1933–2015) and Vitaly Kubasov (1937–2020), the latter formerly among the artist's fellow students at the Theatre Institute, clearly refutes the perception of Russian non-figurative art of the second half of the 20th century as objects of a cargo cult.

Mikhnov-Voitenko. Co-Existence

St.Petersburg, Russia

December 17, 2022 – February 25, 2023