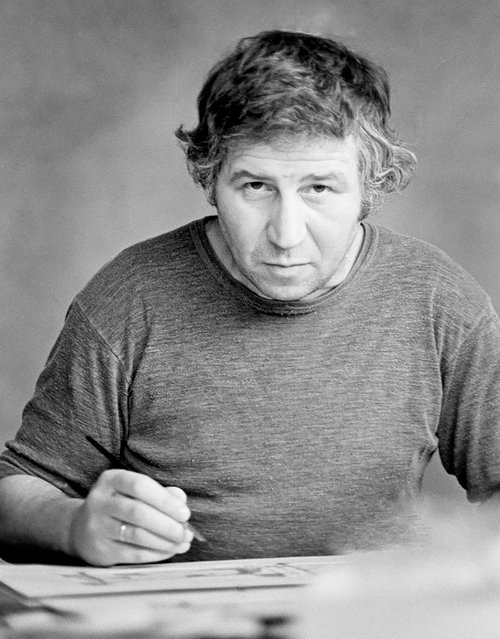

Ilya Kabakov during the installation of 'The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment' (2012) at Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven. Eindhoven, 2023. Courtesy of Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven. Photo by Perry van Duijnhoven

The Kabakovs in the Netherlands and Israel

Eindhoven’s Van Abbe Museum and Tel Aviv Museum of Art have concurrently opened solo shows of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. Although planned months ago, they have become memorials to the late Ilya Kabakov who passed away in May this year.

The Kabakovs in Eindhoven

From July until March 2024 the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven is hosting ‘Relinking: Kabakov Cabinet’, which charts the creative journey of Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023), today considered among the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century. From illustrations for children's books to landmark total installations, documentary works, maquettes, printed editions and recent paintings as well as artworks made together with Emilia Kabakova (b. 1945), who became the artist’s wife and collaborator in the late 1980s, it shows the breadth of their artistic activities.

‘Relinking: Kabakov Cabinet’ was conceived by curator and researcher Willem Jan Renders in conjunction with the acquisition in 2021 of two major paintings by the duo and a series of eighty-five prints. The museum collection itself serves as a context for this show. Alongside European modernist and contemporary art, the collection includes a significant body of works by the suprematist artist El (Lazar) Lissitzky (1980–1941), and in 2012 the museum received a donation of the LS Collection of Albert Lemmens and Serge-Aljosja Stommels, a vast private collection of artist books and Russian lithographed editions from the 1930s. Comprising over 13,000 items from the Soviet and post-Soviet space, it includes artists such as Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013), Francisco Infante-Arana (b. 1943), Mikhail Karasik (1953–2017), Mikhail Molochnikov (b. 1963), Leonid Tishkov (b. 1953), Yuri Albert (b. 1959), Alexander Dzhikia (b. 1963), Pavel Pepperstein (b. 1966) and, last but not least, Ilya Kabakov an artist who excelled in this genre. Marking the donation in 2012, in the same year the museum hosted the exhibition ‘Lissitzky-Kabakov: Utopia and Reality’ also curated by Willem Jan Renders.

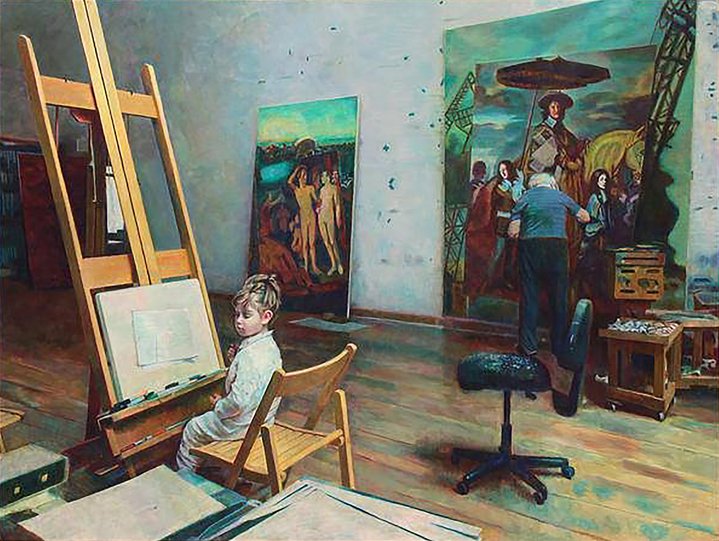

As a kind of prelude to the exhibition the visitor is faced with two large-scale canvases, ‘The Letter’ and ‘Two Times No15’, painterly collages combining fragments of seventeenth century paintings and Soviet era photographs. In the jarring juxtaposition of these two illusory worlds, painted in green colours reminiscent of Socialist Realism, one of Kabakov's main themes – the tragedy of being in a bifurcated, fragmented space – remains the leitmotif.

Then, the viewer advances into the chamber room of the artist's and demiurge's cabinet, where everything is systematised. All is assembled according to themes and groups from the early works to the most recent ones, everything neatly shelved and signed.

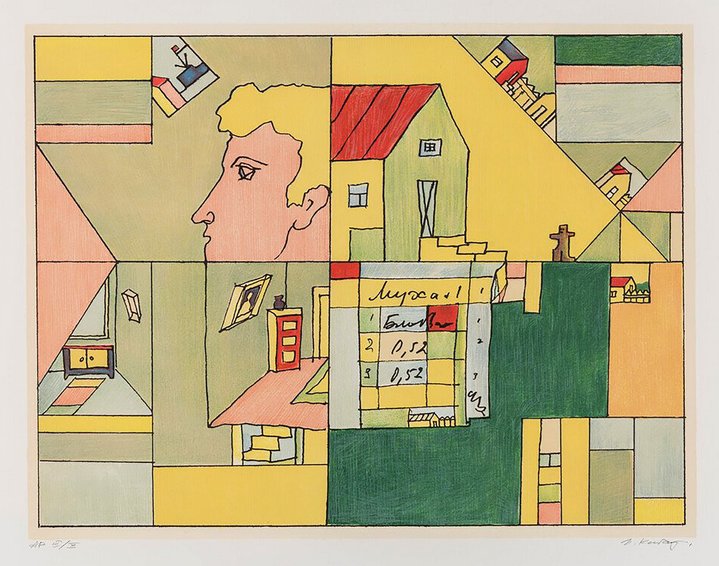

Kabakov was a professional graphic artist and, like many Soviet artists, earned his living by illustrating books, and it was in his spare time that he made art ‘for himself’. In the main exhibition space, this organised cabinet, the exhibition startswith a collage made from scanned covers of children's books and illustrated originals from the late 1970s-1980s which are in the van Abbe collection, including Yuri Kushak's ‘A Ship Sails to Visit’ and Barbara Lewandowska's ‘Far and Near’. Children's books serve as a kind of tuning-fork and appear as commentary later in several other parts of the exhibition. This section also features prints from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, borrowing the language of book illustration, Soviet graphic artists or children's colouring books, but they actually represent Kabakov's idiosyncratic conceptual works. His 1982 ‘Here Are Those Guys!’ is reminiscent of a comic book story about the lives of Soviet boys, but contains visual and semantic irregularities and interventions such as a piece of glass and a ball in the foreground which covers part of the image. The narrative text ends with an absurd commentary and the rhetorical question, “where is my glass"?

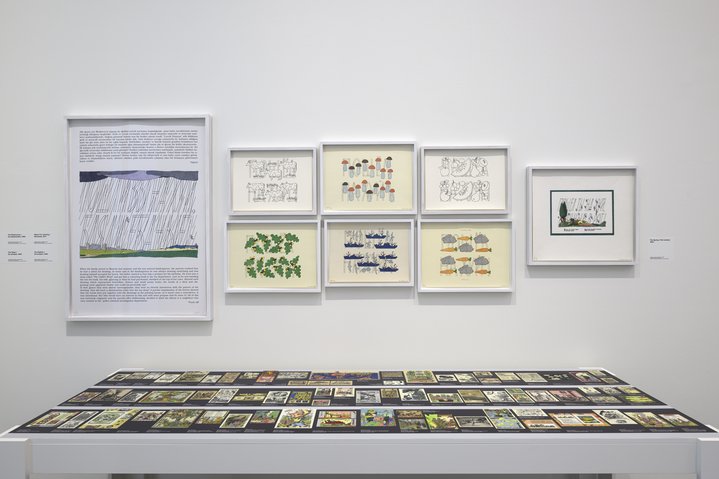

In the pages of one of his best known series ‘Colouring Album’ which he started in 1994 and created over nearly two decades and tells the story about a boy who loved drawing, whose parents bought him a colouring album from the children’s store ‘Detsky Mir’, behind banal images of cows, mushrooms, rabbits and ships, there is the obscene text ‘Fuck off’.

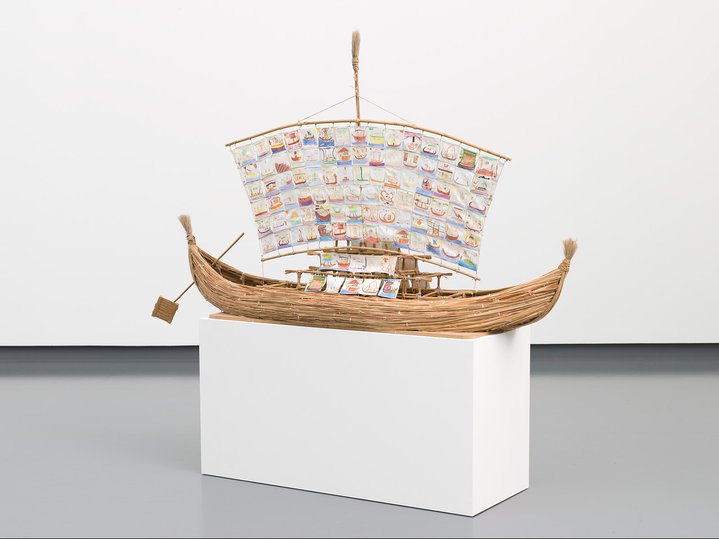

The next part of the exhibition presents two of his most famous total installations, his 1986 ‘The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment’ and ‘The Toilet’ from 1992. That year, at the ninth Documenta in Kassel, the Kabakovs presented a pavilion in the form of a Soviet public toilet with the familiar letters in Russian for ‘M’ and ‘F’, inside which visitors who dared to enter found a cosy domestic interior. One of the artists' later projects from the 2000s is the ‘Ship of Tolerance’, an 18 metre long ship whose sail is painted by children from different cities and countries. The exhibition includes a model of the ship made in 2006, as well as a large-format print from the same year ‘The Ship of Siwa’.

The exhibition ends with a focus on his two main strands of activity throughout the 1990s and 2000s. There is amonumental line represented by projects of cyclopean installations - including the utopian 1999 ‘Project Palace’ - for major museums around the world on which the artists worked right up until Ilya Kabakov's passing. Some of them were executed and some were never realised, projects which the artists continued to develop adding new ideas and making changes.

There is lyrical line which you can see in printed works on the theme of flight, escape from reality, disappearance, an overcoming of the earth's gravity. This is one of the main motifs in Kabakov's oeuvre and is present both in his early albums and installations as well as in his later printed works. The series ‘How to Meet an Angel’ (2000–2014) are variations of hand-drawn drawings with textual commentaries in the form of first-person philosophical reflections. Conversations between Kabakov's ‘little man’ and himself are juxtaposed with an image of a staircase rising into the clouds and a fragile figure standing on the last step and extending her hands to angels floating in the clouds. This project was also realised as a monumental sculpture in 2009 for Amsterdam where it is located in the Oud West district. Two sketches for future sculptural monuments, his 2019 ‘The Five Steps of Life’ and the 2012 ‘The Man Climbing over the Wall’, are also on display in the exhibition.

In a series of small leporellos executed in 2003, ‘Wind, Chalice, Sleep’, the protagonist is a conventionally drawn nude man who resembles a comic book hero, standing under a shower where the water plays with him, taking on different forms: a growing and disappearing bubble, an ancient vessel, and sometimes the outline of a woman's profile.

The exhibition poignantly concludes with two small photocollages from 2022, a project for a ‘Monument of Tolerance’for Dnipro (formerly Dnepropetrovsk), the Ukrainian city where Ilya and Emilia Kabakov were both born.

If the objective of the exhibition is firstly to immerse local audiences in the Kabakovs' universe - presented in the context of the museum's collection – then the collection of artist books and finally to showcase new acquisitions, it can be widely considered a success. However, for the sophisticated viewer familiar with unofficial Soviet art, early works and installations by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, the exhibition, in which edition dominated by prints from the 1990s-2000s, it may seem a bit simple. The systematic approach and desire to present the collection in its entirety do not leave the viewer with much free space or the possibility of unhurried reflection which is necessary for an emotional dialogue with the artists' works.

The Kabakovs in Tel-Aviv

Preparation on the first solo exhibition dedicated to the Kabakovs in Israel, ‘Ilya & Emilia Kabakov: Tomorrow We Fly’ started a year and a half ago and it was scheduled to coincide with the 90th anniversary of Ilya Kabakov on 30 Septemberthis year. But after the artist’s passing in May the exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art instead turned into an ‘In Memoriam’ event.

Planned in 2021 and before the armed conflict in Europe, an unimaginable state of affairs sparking a flow of repatriates from Ukraine and Russia to Israel which has increased fourfold, exceeding 100,000. It is a new aliyah rich in creatives and for whom an exhibition of Ilya Kabakov, Russian art’s most famous artistic prodigy in contemporary times, born in Soviet Ukraine, in the city of Dnepropetrovsk, (today's Dnipro), is a momentous event. It acts as a boost for Russian-speaking artists arriving in the country.

The artistic duo Ilya and Emilia Kabakov are among the brightest representatives of post-war Conceptualism. Along with the likes of Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945), Yves Klein (1928–1962), Marina Abramovic (b. 1946), Piero Manzoni (1933–1963) they extended the boundaries of conventional art, enriching it with iterations of installation, action and public art. The Kabakovs both created and reflected on their work, which is why the written text is so important in their works. Conceptualism is a complex intellectual game, a delight for an educated viewer with a philosophical turn of mind.

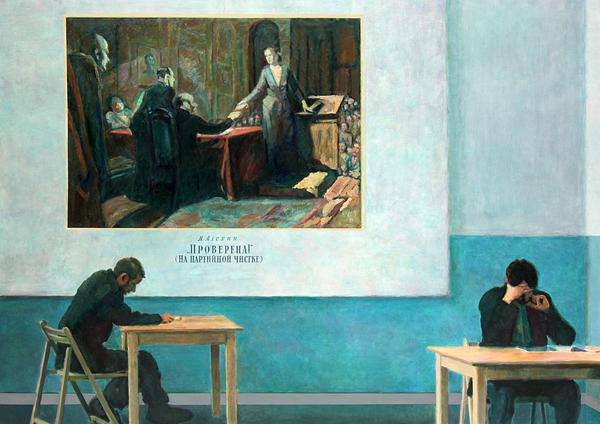

The Kabakovs' main theme was Soviet civilisation, and they explored the Homo Soveticus, as writer Alexander Zinoviev dubbed him/her, with its ideological rituals (the 1981 painting ‘Checked. On Party Purge’, an ironic paraphrase of the famous 1936 painting by artist I. Alekhine), the everyday life of a communal flat (the scandalous 1992 installation ‘The Toilet’), and the stultifying daily routine of basic physical survival in a totalitarian society. For a long time it seemed that the Kabakovs, with their focus on the inhumanity of Soviet life, were exaggerating, because these horrors were in the past, this page of history had been turned. But the events of recent years have shown that they were visionaries.

"The way Kabakov analysed, felt and showed the Soviet state”, comments gallerist and collector Yulia Guelman, "in all its gigantic horror of violence against man and humanity, with its vulgarity, bureaucracy and kitsch, is quite unique. This agenda is super relevant today."

The selection of works at the exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art has perhaps been shaped by current events. Thereare almost none of the major works which were shown at the Kabakovs’ landmark exhibition at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in 2018: not the famous ‘Beetle’ (the artist's most expensive painting, sold by auction in 2008 at Phillips de Pury in London for almost $6 million), nor the 1982 installation ‘The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment’, nor his poignant ‘Labyrinth (My Mother's Album)’. But there is the installation‘The Eminent Direction of Thoughts’ made in 2017 for the exhibition ‘Luther and the Avant-Garde’ in Wittenberg, Germany, curated by Dimitri Ozerkov. It comprises a prison cell, a single chair and illuminated multicoloured threads running from the chair to the ceiling, a metaphor for the infinite power of the spirit and imagination.

The works in the exhibition were borrowed from several dozen museum and private collections and it is not by chance many were unavailable. The largest number of works by Ilya Kabakov are in the collection of Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, and several other important paintings from the 1980s are in the MAGMA collection belonging to Vyacheslev Kantor.

The show includes references to the Soviet myth: in the first hall the viewer is greeted by a large densely-painted steam engine, from the song ‘Our Steam Engine Go Ahead...‘ with the inscription ‘Next Stop Tarakanovo’ (1979). But the centrepiece of the exhibition is Ilya Kabakov’s 1993 installation ‘The Empty Museum’, a model of a classical museum room with red illuminated walls, but no paintings. Johann Sebastian Bach's Passacaglia is played in the room, and you can sit down on bench and immerse yourself in music and contemplation. The space itself becomes a hymn to culture, an affirmation of art and the museum as the guardian of our highest cultural values. This mood continues in the next work, the 2002 installation ‘Where We Belong’ in which we see the giant feet of some Gullivers looking at huge paintings. And at the same time, at floor level, under glass, the landscapes of the Lilliputian world are constructed, while we the viewers find ourselves between these two worlds and can look at a selection of TASS (Soviet and later Russian government news agency) photographs, complemented by exquisite poems with a kind of hokku in English:

The moon, bathing, quivered. I stood for a long time. The hall roared.

As Emilia Kabakova, who attended the set up and was present on the opening night says, "Art is the only thing that keeps us on a human level”. Or we invariably sink to the level of the crowd. In the end, Kabakov's cultural pathos has clearly outweighed its socially denunciatory motive