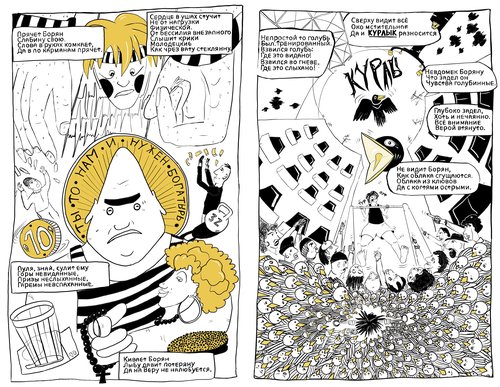

This Is the Best We Have. Still from the movie. Courtesy of The Art Newspaper Russia

The Art Film Festival 2025: Documentaries that Defy Borders

Now in its eighth year, the Art Film Festival (TAFF) spans Moscow and seven additional Russian cities this Autumn, offering a sharp perspective on today’s shifting cultural landscape. Despite a fraught international climate, The Art Newspaper Russia and the In Artibus Foundation have delivered a programme which stands out for its remarkable curatorial resolve.

The programme’s stated theme – ‘national identity and the connection between cultures’ – feels especially resonant now, serving as a quiet lens through which to gauge Russian art’s place in the world and in its own past. The inclusion of films from nine countries – including the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and Japan – stands as a clear testament to a team that steered through substantial cooperation hurdles.

The domestic programme signals a systematic effort to record and preserve the history of Russian contemporary art as part of the country’s ongoing cultural self-reflection. Its centrepiece, the mockumentary ‘This Is the Best We Have’ – The Art Newspaper Russia’s cinematic debut, based on its eponymous MMOMA exhibition – doubles as a witty ‘video-catalogue’: a passerby wanders into a show, opening up the clichés and questions that both irk and amuse museum-goers. Starring Anton Lapenko and Alisa Kretova, the film is enjoyable and genuinely instructive, illuminating figures such as Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) and Erik Bulatov (b. 1933).

Serving a similar purpose is the documentary ‘Anatoly Belkin. High Water’ which focuses on one of the heroes of unofficial Soviet art. Filmed in a format where the camera follows the protagonist, it provides a vivid biography of the artist Anatoly Belkin (b. 1953) and offers the viewer a peek into his daily life, while preparing his show at the Hermitage. Documenting the history of Russian contemporary art is an essential undertaking that today seems impossible without the support of private art patrons and philanthropists. Fortunately, organisations like the privately owned AZ Museum exist, and they make work like this possible.

Not all domestically produced works achieve strong cinematic craft. Despite rich material – renowned speakers Natalia (b. 1958) and Valery (b. 1948) Cherkashin and key episodes like their early-1990s interventions at Moscow’s Ploshchad Revolyutsii – Cherkashins. Perestroika Performance looks and sounds curiously time-warped, as though produced in the perestroika era. Birds of Joy and Sorrow likewise venerates Russian majolica but feels constrained and overly pompous. The takeaway is clear: Russia lacks a robust cadre of directors skilled in art documentary – a gap private philanthropists could help close through targeted support and development.”

In the international section of the festival the curators demonstrate a wide and eclectic range, featuring delicate, meditative works alongside more straightforward genre pictures. It seems to be less about prestige and more about charting a new world order, particularly the cultural reorientation of Russia toward the Global South. The most tangible sign of this shift is, perhaps, the inclusion of the Nigerian film ‘When Nigeria Happens’ which premiered at the Locarno Festival. This vibrant film explores the social difficulties facing contemporary Nigerian dancers, offering Russian audiences a rare glimpse into a reality far removed from their own experience.

The Chinese animated film ‘The Story of Fire’, nominated for the best children’s film of Berlinale, executed in the style of traditional ink painting, essentially could be watched and perceived as video art – an elegant epic based on an ancient Chinese legend that conveys a universal archetypical hero myth. Another documentary from China is called ‘Cha-Cha-Chinatown’ and is an insightful look at Chinese American identity through the lens of a 92-year-old burlesque star. One more highlight of the Asian section, the fundamental British-Japanese-French documentary ‘Pioneers of the Japanese Avant-Garde’ would undoubtedly be obligatory viewing for anyone looking to gain a deeper understanding of Japanese culture and contemporary art.

Among the European entries, highlights include ‘Stolen Caravaggio’ a detective thriller set against the beauty of the Maltese landscape, and the Italian film ‘The Tyrant’s Conspiracy’ about a major hoax in modern art history. Both prove that even the most rarefied subjects can serve as the backdrop for taut, genre-bending cinema. The American entry, ‘The Exhibition of Forgiveness’, one of the Sundance 2024 selection, is a psychological drama, focusing on a successful artist’s difficult reunion with his formerly addicted, homeless father.

Finally, there is Boris Yukhananov’s epic five-hour film diptych, ‘Integral Calculus’. This experimental project by the late visionary theatre director is essentially a video recording of a lengthy performance at the Electrotheatre Stanislavsky in Moscow. With some irony, it feels a bit like Matthew Barney (b. 1967), but a more budget version. Viewers follow the director’s dreams and fantasies navigating through an ancient Roman set with texts by William Shakespeare and Antonin Artaud, songs by post-soviet pop stars, and travels in space. Nevertheless, this ambitious programming pick is entirely justified by the scale of Yukhananov’s impact and importance in the history of Russian culture. At the very least, it demonstrates the wide range of art-cinema production that can be seen at festivals today.

The overall impression of TAFF remains strong. At a time when bringing international films to Russia demanded Herculean efforts, the festival’s curatorial team has managed to assemble a programme that not only documents local heritage but also opens a window onto new, often inaccessible cultural regions.

The Art Film Festival

Moscow, St. Petersburg, Ekaterinburg, Vladimir, Perm, Samara, Novosibirsk, Nizhny Novgorod. Russia

20 October – 2 November 2025