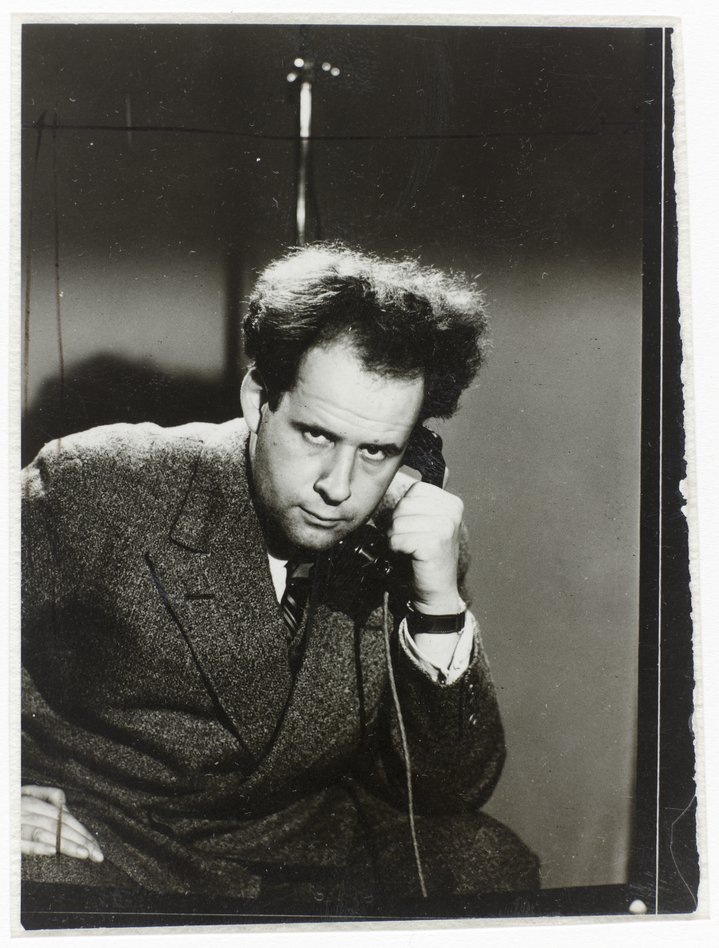

The all-seeing eye of Sergei Eisenstein

Alexander Rodchenko. Poster for the "Battleship Potemkin" 1926 101 x 72 cm © Adagp, Paris, 2019 © A. Dobrovinsky Collection

The Pompidou Centre's branch in Metz is staging a retrospective of the multifaceted Russian genius which covers the whole scope of his work, from cinema to graphic .

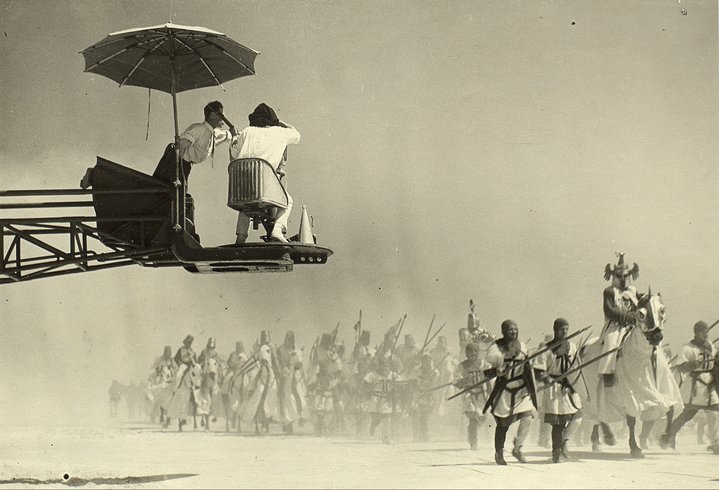

The name of Sergei Eisenstein is inextricably linked to his masterpiece, the 1925 film “Battleship Potemkin,” from which he "woke up famous" and at the helm of Soviet cinema: at the time, still a young form but the "most important of the arts," according to Lenin.

His innovations in editing and lighting were so brave and effective, revealing new potential for the moving picture and propelling his fame and influence far beyond his homeland. Now a staple in the first chapter of any film studies syllabus, Eisenstein is revered by film buffs and directors for his seven feature films, which eventually found their place in the pantheon of cinematic history. Martin Scorsese and Peter Greenaway are among his devoted admirers.

But the figure we have come to see now as a cinematic colossus par excellence had a complex and convoluted journey, littered with many failures and rejections on the one hand and a hugely rich and varied cultural life outside cinema on the other. The latter continues to be revealed and reconsidered today.

Born in what was still the Russian Empire and raised in a tradition of European culture, with a deep immersion in the history of art, architecture, literature and philosophy, Eisenstein was a constantly evolving polymath. He worked in theatre, was an outspoken film theorist and engaging teacher. Eisenstein’s travels alone deserve a separate volume: from a European tour to crossing the Pacific to Hollywood and a later trip to Mexico, mingling among such legendary figures as James Joyce, Charlie Chaplin, Frida Kahlo and Diego Riviera, to name but a smattering. Yet he certainly didn't have an easy ride: dodging and appeasing Soviet censorship in his homeland; hopeful pitches to Hollywood that went nowhere; a further escapade in Mexico that ended abruptly with a forced return to the USSR, leaving behind several hundred thousand feet of film reels and an entire unfinished project. Evacuation to Kazakhstan ensued in the 1940s.

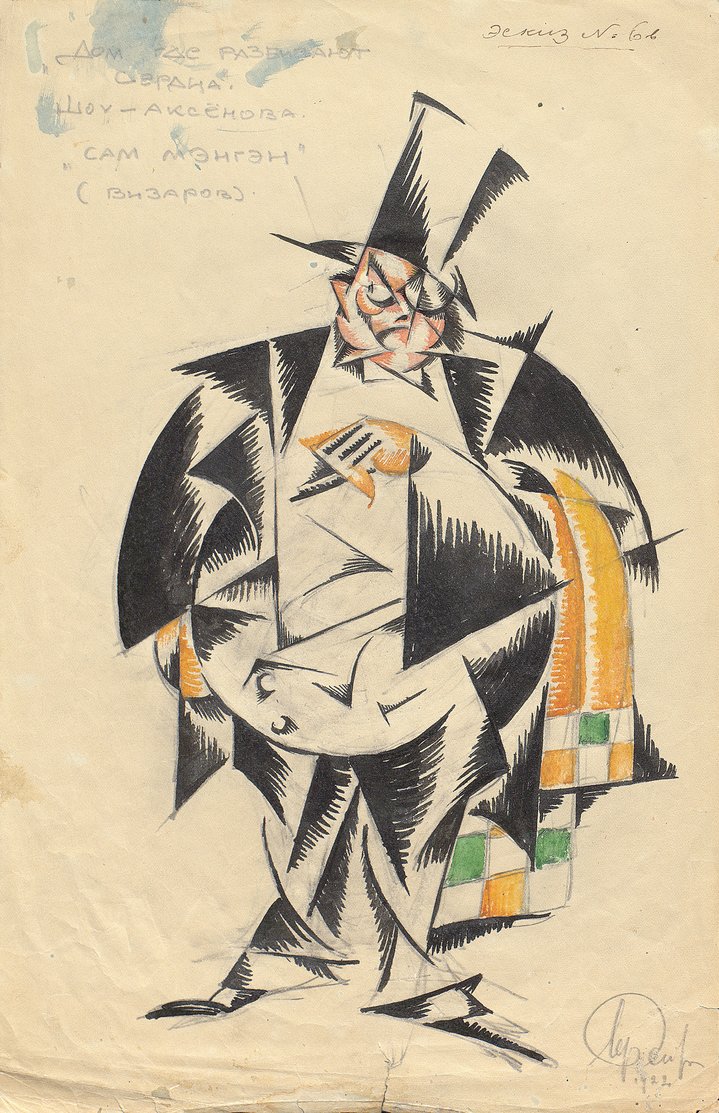

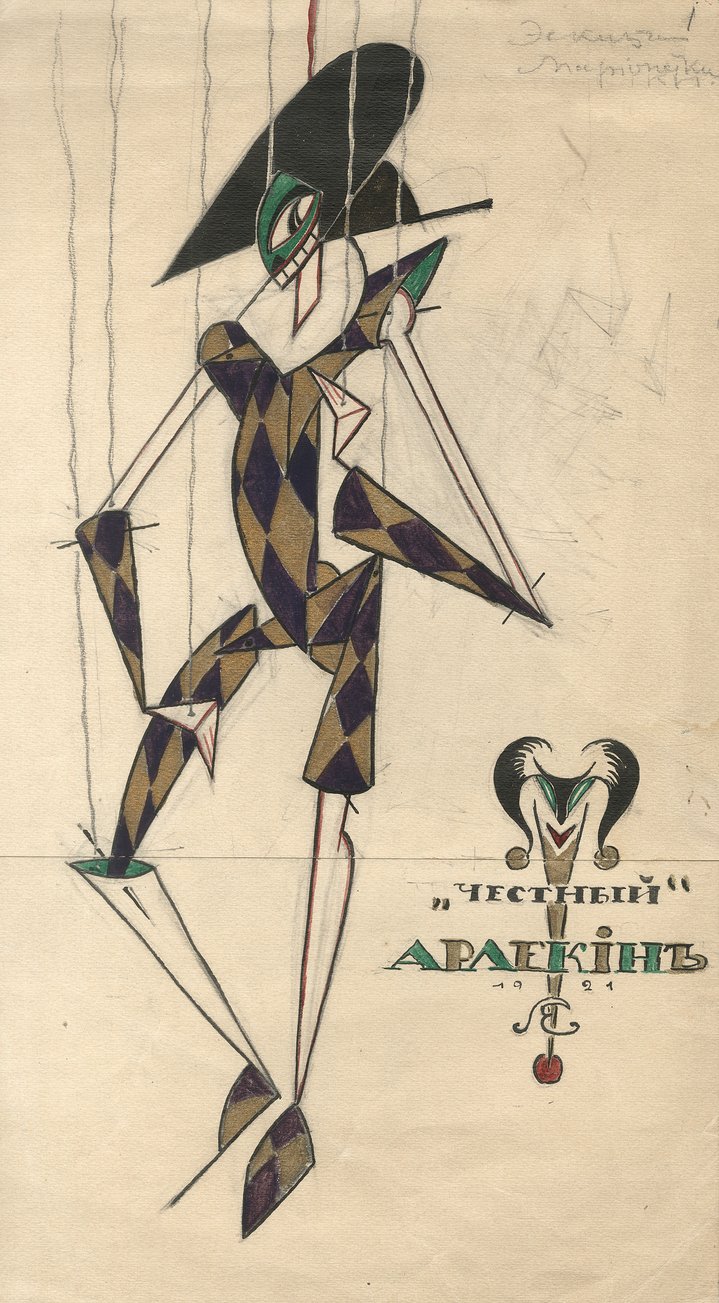

The abandoned Mexican footage was cut and re-cut by subsequent generations in an attempt to convey his vision — or impart their own. It seems that Eisenstein's own life and persona received similar treatment, and it's no wonder: such ample material demands a fresh edit. Such is Peter Greenaway's recent biopic, for example: foregrounding the risqué subject of Eisenstein's sexuality, where a homosexual encounter in Mexico is given centre stage as crucial to his personal awakening. Another overlooked side of the author which has been getting increased attention recently is his prolific artistic output. There are thousands of sketches that have been kept primarily in Russian archives, a small fraction of which — about 500 — have recently been published (with a foreword by Martin Scorsese) as "Eisenstein on Paper: Graphic Works by the Master of Film" (Thames&Hudson). Previously overshadowed by a colossal cinematic reputation, the drawings are gradually emerging in their own right: not just storyboards or costume ideas, but visual diaries and outpourings of self-expression, they recorded what he couldn’t or dared not otherwise formulate for whatever reason. Stalin’s all-seeing eye scrutinised every film script, but these drawings could slip past the censors. Sergei Prokofiev "read" the visuals when composing the score to Eisenstein’s later films at a time when written instruction would have been too dangerous.

The drawings’ deft linearity and elegance bring to mind a visual parallel, Jean Cocteau. Born only a decade apart, both these maverick directors were talented draftsmen, but unlike Cocteau, few would call Eisenstein an artist in a game of word association. Perhaps it is then fitting that the most thorough attempt at redressing this balance is now being launched in France, the birthplace of cinema. The Centre Pompidou in Metz is putting on a broad exhibition, "The Ecstatic Eye. Eisenstein, a filmmaker at the crossroads of the arts," which draws parallels between the visuals of Eisenstein’s cinema and his artistic vision, personal creativity and historical references. They literally pull his films out of the cinema and into the exhibition space. After almost a century, we can hope that his multifaceted genius will be revealed, his oeuvre reconsidered and that new light will be shed on a figure of such monumental dimension.

The Ecstatic Eye. Eisenstein, a filmmaker at the crossroads of the arts

Metz, France

28 September 2019 – 24 February 2020