Beyond Gender and Central Asia: Saodat Ismailova

Saodat Ismailova. Eye Art & Film Prize Winners opening. Photo Maarten Nauw

After showing her works recently at both the Venice Biennale and Documenta, Uzbek-born, prize-winning artist and filmmaker Saodat Ismailova is starting the new year with two personal exhibitions in France and the Netherlands.

Raised in a family of filmmakers and herself a film director, Saodat Ismalova (b. 1981) still finds it strange to call herself an artist. When it comes to her professional identity it is hard to settle on one overriding vocation. Ismailova is an artist, videographer, screenwriter, film director and in many ways also an ethnographer. Speaking about her roots she prefers to present herself as an artist from Central Asia, without limiting herself to her homeland Uzbekistan. Indeed, the notion of Central Asia as defined by Humboldt draws out the deep existing connections between Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Uyghurs, Tatars, Iranians, and Northern Afghans. On the other hand, she was born in the late Soviet Union, and its specific heritage with all its plusses and minuses have also formed a part of her personality.

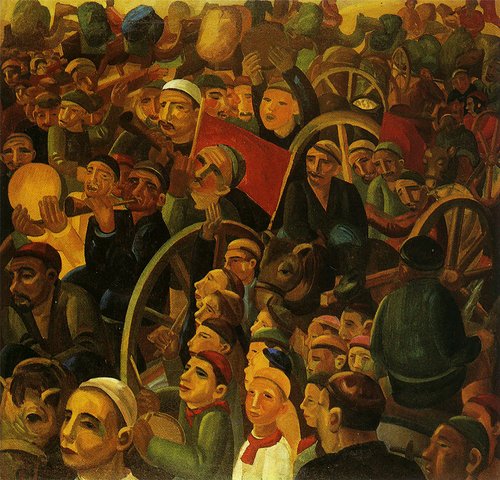

Saodat Ismailova has always been fascinated by the sort of deep human connections you find through shared memory, in nature and spiritual experiences. Traumatic colonialism and later Uzbekistan’s Soviet past has not been able to eradicate the roots which bind different generations and nations regardless of political structures. To reflect these states, Ismailova has always liked working with moving images, whether it is a film or a video installation.

Ismailova graduated from Tashkent State Art Institute, where she learned the traditional art of filmmaking. Paradoxically only after coming to Europe, did she discover the whole, rich palette of Soviet cinematography, such as films by Artavazd Peleshyan or Sergey Paradzhanov. Her documentary ‘Aral: Fishing in an Invisible Sea’ won the Best Documentary at the 2004 Turin Film Festival, then her feature film ‘40 Days of Silence’ was shown at Berlinale. It could have continued on like that, but she felt that there were other new horizons for her to prize open. During her art residencies in Italy, Germany and Norway Saodat Ismailova reflected on the limits of cinematography and started to experiment more widely. Now, living between Paris and Tashent, it is always Central Asia she goes to when she is looking for inspiration.

Initially, Ismailova was seen as post-Soviet artist and back in early 2000s it was even hard for people to pronounce ‘Uzbekistan’; people often did not know where it was. This label appeared again during the preparation of her solo show ‘Double Horizon’ in the north of France at the National Studio of Contemporary Arts ‘Le Fresnoy’ in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou. Curators Marcella Lista and Pascale Pronnier wanted to show five of her works in dialogue with artworks from the Pompidou collection itself. They began to work on a selection together. Soon it was clear that Ismailova’s art practice does not limit itself even to Central Asian, or even post-communist art, nor to female art. It was important to find its conceptual connections, bringing on the inclusion in the show of works by Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), Mona Hatoum (b. 1952), Fiona Tan (b. 1966) and Zineb Sedira (b. 1956).

The generation gap has been very profound in Uzbekistan. Not because of intergenerational misunderstandings, but because of a strong fear, as Ismailova puts it, that after the forced change of the alphabet in 1928 (during one century the Uzbek alphabet was changed three times from Arabic, to Latin, then to Cyrillic and back to Latin), the loss or ban of a huge tranche of national heritage, the severance of fundamental cultural links with Iran and Afghanistan, it was very difficult to determine what exactly the previous generation could convey. A fear of one’s own indigenous culture was and still is a very common feeling for countries that were colonised by the Russian empire and then were included in the USSR. People who were ‘illegally’ practicing their own native culture were putting themselves and their families at risk. However all this did not and could not eradicate thousands of years of history. In the case of Uzbekistan, it’s Buddhist, Zoroastrian, Pre-islamic, Islamic and agnostic cultures. Ismailova believes strongly that pain, shaped by a prohibition to turn to one's roots, has ended up activating a shared energy and the need to keep memories alive and work out one’s own identity.

One way of working with memory is silence. In Ismailova’s first feature film ‘40 days of silence’ is dedicated to the 40-day vow of silence taken by women immediately after marriage, death or birth of a family member. Through silence they adapt to their new stage of life, trying to find out who they are, being lost and facing the obscurity. And while she was editing that film, Ismailova created her first video installation ‘Zukhra’. It was made in 2013 for the last Central Asian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and now is on permanent public view at Stedelijk museum in Amsterdam. For Ismailova this kind of silence is more a practice of self-discovery, rather than the embodiment of oppression. ‘This is how you meet your animal origins’ she explains. A vow of silence used to be very common in the region and is still practiced by shamans and healers today.

Nature is something that regardless of historical turns, has always been present. When in 2003 Ismailova started work on a huge documentary series about music of Central Asia, she spent a decade travelling around the region. It was during that period that she first started to see Central Asia as one entity, as a united organism with its inner connections. In a way it was an anthropological and ethnographic expedition. In her work ‘Stains of Oxus’ we hear a story about a girl called Soman who, wanting to escape from an unwanted marriage, became a lake, and now fishermen talk to her through the water. Nature is perceived as a guardian and something sacred. In ‘The Haunted’ Ismailova tells a story of a Turanian tiger that was exterminated during the Russian colonisation of Turkestan. Local people still worship and pray to this animal. ‘They've been killing you for a long time, I'm sorry I didn't save you. They stole our Paradise, they burned our garden’, says a voice in the video. As Ismailova sees it today, the notion of Central Asian culture still needs to be crystallised and analysed. And it can only be locals who can do this. She feels that when speaking about gender or nation, it’s important not to structure an identity using victimhood as a starting point.

Being an authentic cinematographer, Ismailova has always imagined image together with sound. Sound plays an important role in her work. She collaborates with sound designers and composers in order to create a precise and conceptual sound environment. However she has only used traditional music once in her work Qyrq Qyz, a musical performance, premiered at Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York in 2018. ‘We have to treat traditional music very carefully so that we don't fall into self-exoticisation. Such music in itself is very self-reliant’.

The Uzbek language is Saodat’s mother tongue, however she went to a Russian-speaking school and university. Today she admits that she can explain sophisticated things better in Russian than in Uzbek. And this is not because of her linguistic abilities, but because of a persistent state of language politics. ‘We didn’t know much Uzbek literature, poetry’, she explains. First she read a national epic in the Russian translation made by poet and turcologist Arseny Tarkovsky. In the monologue from ‘The Haunted’ we hear: ‘I woke up in the steppe. My family spoke a language that was not familiar, now I speak languages that are not mine’.

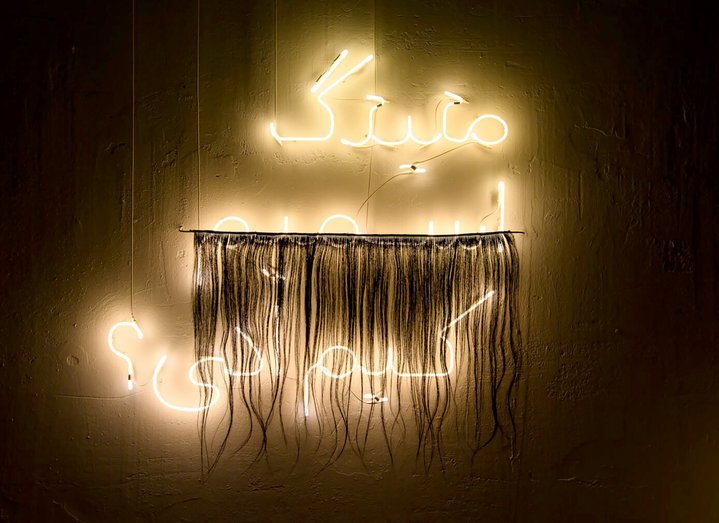

In 2022 Ismailova was awarded an Eye Art & Film Prize for her work that ‘touches the edges of film language’. The prize was followed by the announcement of her forthcoming exhibition in the Eye Film museum in Amsterdam. Currently she is working on a new video piece ‘18 000 worlds’ especially for her new show. This iconic place, a major Dutch cinematheque, will show twelve works by Ismailova, her neon sculptures and her new video installation. It reflects on a concept of 18 000 worlds that exist in mystical Islam, our colonial past and the transmission of the memory, and ephemeral nature of human culture.

Saodat Ismailova. 18 000 worlds

Amsterdam, Netherlands

January 21 – June 4, 2023

Saodat Ismailova. Double horizon

Le Fresnoy – National Studio of Contemporary Arts and Centre Pompidou

Tourcoing and Paris, France

February 10 – April 30, 2023