Rozanova’s Green Stripe Stars in St Petersburg Retrospective

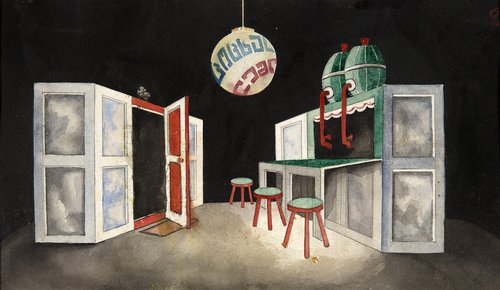

Olga Rozanova. Desk, 1916. Courtesy of the State Russian Museum

Olga Rozanova's work, including her iconic ‘Green Stripe’, is gaining recognition today for its profound impact in bridging early 20th century Russian movements and post-war abstraction in Europe and North America.

This finely tuned yet modest survey of Russian avant-gardist Olga Rozanova (1886–1918) is laid out over just four rooms at the State Russian Museum. It comes after a bigger show last year in Moscow at GES-2 called ‘A Cup of Consonances. Approaching Rozanova’, which presented her work together with contemporary artists and was something of a homage to this amazon of the avant-garde. Rozanova, who died at the age of 32, has long remained in the shadow of more productive artists of the time like Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), Liubov Popova (1889–1924) and Alexandra Exter (1882–1949) yet her 1917 painting‘Green Stripe’ rightfully occupies its own place on the front line of art history alongside iconic abstract art works from the likes of Kazimir Malevich (‘Black Square’), Vassily Kandinsky (‘Composition V’) and Piet Mondrian (‘Composition I’). Prior to these two solo shows, Rozanova's previous retrospective took place three decades ago in 1992, a travelling exhibition which was shown at the State Russian Museum, the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Helsinki City Museum in Finland.

Olga Rozanova was born into a noble family in the town of Melenki, Vladimir province in Central Russia. Aged eighteen she travelled to Moscow in 1905, where she studied in private schools and art studios. She met up with artists and peers who shared a common passion for modern painting. In 1908 an exhibition in Moscow presented works by the most famous French artists of the time, ranging from the Impressionists to the Cubists. Quickly and with ease, Rozanova mastered the techniques of Impressionist painting, experimented with the Jack of Diamonds group of avant-garde artists heavily influenced by French styles, before becoming more fascinated with Cubism and Futurism. In 1910 she helped to establish the ‘Union of Youth’ artistic society and by autumn of 1911 she had moved to St. Petersburg, where she joined a group of leading artists that included Mikhail Matyushin (1861–1934) and his wife Elena Guro (1887–1913), Pavel Filonov (1883–1941), Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) as well as the poet Velimir Khlebnikov (1885–1922).

Rozanova, was also a talented writer and she wrote poetry and composed the ‘Union of Youth’ manifesto in 1913. Since manifestos were a feature of the times, it echoed themes common to the day: "We declare a struggle against all the jailers of the Free Art of Painting, who have shackled it in the chains of everyday life: politics, literature and the nightmare of psychological effects. We declare that the painter can only speak in the language of pictorial creative experience, without going into the pockets of other people...We declare that all paths are good, except those that are beaten and polluted by other people's innumerable steps, and we appreciate only those works that by their novelty give birth to a new human being in the viewer!".

Freely expressing herself in the visual language of her time, Rozanova illustrated small edition publications of the Futurists and published a number of books along with the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh (1886–1968). Among the linocuts she created for the album ‘War’, which featured poems by Kruchenykh and was published in Moscow in 1916, she included images of "excerpts from newspaper reports" describing the horrors created by the army of the aggressors. She was to call this collection "her highest achievement in printmaking". In 1916, she joined the ‘Supremus Society’, founded by Malevich, coming up with the idea of transformed colour and the technique of the atomisation of colour in works she produced during this phase. "Rozanova's Suprematism is opposite to [that of] Malevich's Suprematism, which builds its works on the composition of square forms, while Rozanova builds – on colour", the artist Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958) wrote in 1919. At the end of 1916, Rozanova returned to Moscow in time to witness the beginning of the revolution. For her, transfigured colour painting had an obvious connection with the transformation of the world by the revolution. Actively engaged in supporting folk crafts, she created designs for dresses and even a woman's handbag for ‘Verbovka’, the cooperative workshop. In November 1918, Rozanova died of diphtheria and was buried in the cemetery of the Novodevichy Convent. Her grave no longer exists.

The story of the search for and the preservation of her works is an integral part of the account of the artist's fate. At her posthumous exhibition in Moscow in 1919, two hundred and fifty paintings were included, but the catalogue was published without illustrations, and many of her abstract works had identical titles, making attributions difficult today. The list of museums that provided works for the current exhibition is unusual, with the State Tretyakov Gallery and the State Russian Museum playing lesser roles than might have been expected. The most famous work by Rozanova is to be found in the small town of Rostov, in the Rostov-Yaroslavl Museum of Architecture and Art. Other works come from state collections in cities of central and north-eastern Russia including Arkhangelsk, Veliky Ustyug, Kostroma, Totma, and Yelets. The Museum of Pictorial Culture, which was founded in Moscow in 1919, promoted new art and distributed works to cities far from the capital and it was thanks to this policy that many of these works survived in small museums during the Soviet era.

Yevgeny Kovtun, who has dedicated his life to researching the Russian avant-garde and previously worked at the State Russian Museum, writes about her: "A sensitive artist, Rozanova is like a barometer that predicts a few changes in the weather." Her early work stands up to comparison with her Western European contemporaries, such as ‘Red House’ (1910), ‘Cityscape with a Coachman’ (1910) and ‘Forge’ (1912), all displayed in the State Russian Museum. Her 1915 collage ‘Composition with Cards’ evokes Henri Matisse's ‘Jazz’, which appeared in a very different era. The orange rectangles in her 1917 ‘Objectless Composition’ in the collection of the State Russian Museum brings to mind the minimalist abstraction of Josef Albers (1888–1976) from his Black Mountain College years. Finally, ‘The Green Stripe’, painted in 1917, despite its modest size precedes by three whole decades the large-scale canvases of Barnett Newman (1905–1970). The connection between Rozanova's Suprematist works, and post-war American and European abstraction is not only about the external similarity of forms, but it also literally confirms the predictive properties and powerful potential of the avant-garde of the 1910s as Rozanova and her contemporaries looked to the future.

Olga Rozanova: An Art Revolutionary

St. Petersburg, Russia

May 16 – September 1, 2024