A Cup of Consonances: Approaching Rozanova. Exhibition view. GES-2 House of Culture. Moscow, 2023. Photo by Daniil Annenkov. Courtesy of GES-2 House of Culture

Futurism’s Androgynous Path

‘Cup of Consonances. Towards Rozanova’ at GES-2 in Moscow is the largest exhibition ever staged of the artist's creative heritage and is uniquely framed by other leading female artists from Soviet and post-Soviet Russia.

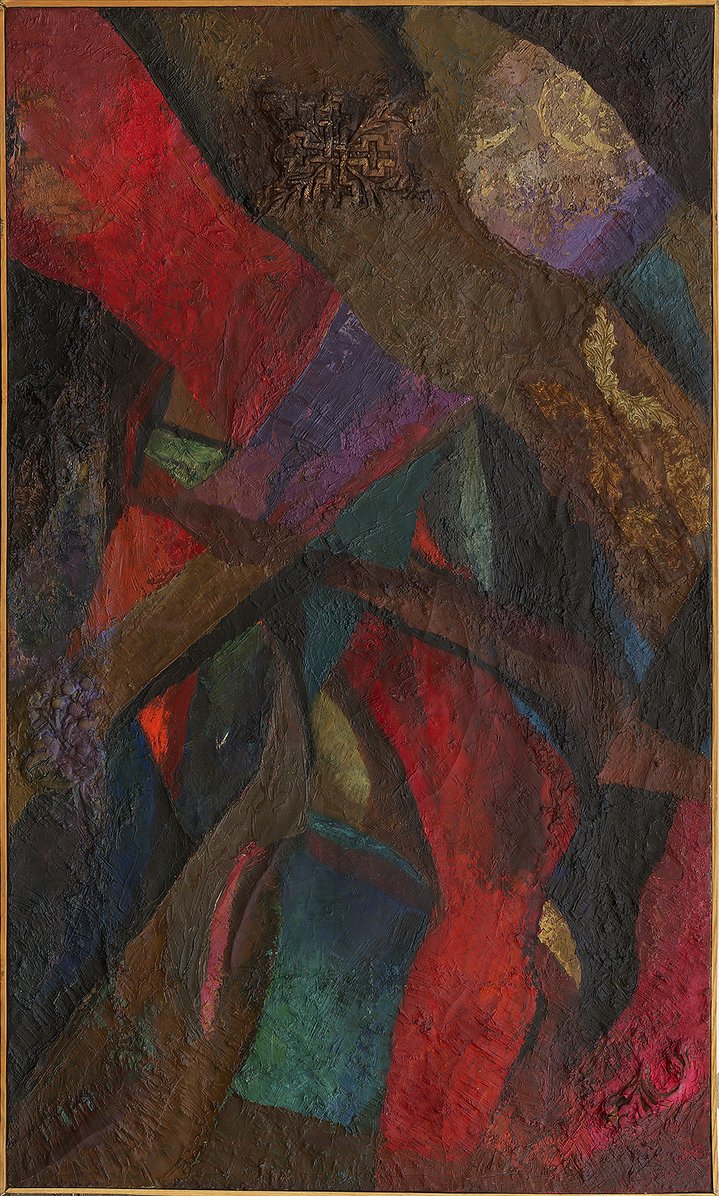

The retrospective exhibition of Russian avant-garde painter Olga Rozanova (1886–1918) is more than just a comprehensive survey, it is a palimpsest. Her work is set amongst paintings by non-conformist artists such as Lidiya Masterkova, (1927–2008) and Efrosinya Ermilova-Platova, (1895–1974), as well as more recent contemporary female artists. It is a nuanced approach by curators Andrei Parshikov, Karen Sarkisov and Elena Yaichnikova in which one element seems to shine through the other. A layered exhibition space modelled by architect Sasha Kim allows Rozanova's luminous lines and planes to light up coloured tables by Alena Kirtsova (b. 1954) and star charts by Alexandra Paperno (b. 1978). Iza Genzken's (b. 1948) laboratories consisting of simple volumes and coloured planes and the fading concreteness of Bella Pokrova's (b. 1997) porcelain ‘Cradle’ resonate with ideas of synesthesia of matter, colour, light, sound and word that were developed by the Russian Futurists, primarily by the tandem of Olga Rozanova and Aleksei Kruchyonykh (1886–1968).

This layering and porosity of various plots and substances echos Rozanova's own understanding of the new universe avant-gardists were searching for, in which the binary opposites ‘body – space’, ‘word – image’, ‘paint – colour’, and, finally, ‘male – female’ were to be erased in a new non-binary universe. Olga Rozanova is seen as an ‘amazon of the avant-garde’. This definition became a meme for the Russian cubo-futurists active in the 1910s including, also, Alexandra Ekster (1882–1949), Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), Liubov Popova (1889–1924), Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958) and Nadezhda Udaltsova (1885–1961) after a legendary exhibition ‘Amazons of the Avant-Garde’, which travelled through Europe and the USA from 1999 to 2001. This exhibition helped to solidify Olga Rozanova’s international recognition. The catalogue for the 2001 exhibition contains an interesting article by Olga Matich entitled ‘Gender Problems in the Kingdom of the Amazons: Images of Women in Russian Culture at the Turn of the Century’. Olga Matich writes about the specifics of androgyny in Russian Symbolism and the early avant-garde. In contrast to the negative meaning of the word ‘androgyny’, which once meant fear of castration and degeneration, Russian philosophical thought of the Silver Age adopted a different, positive meaning. Philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, for example, had in mind a spiritual Platonic hybrid, a symbol of the immortality of spirit and body.

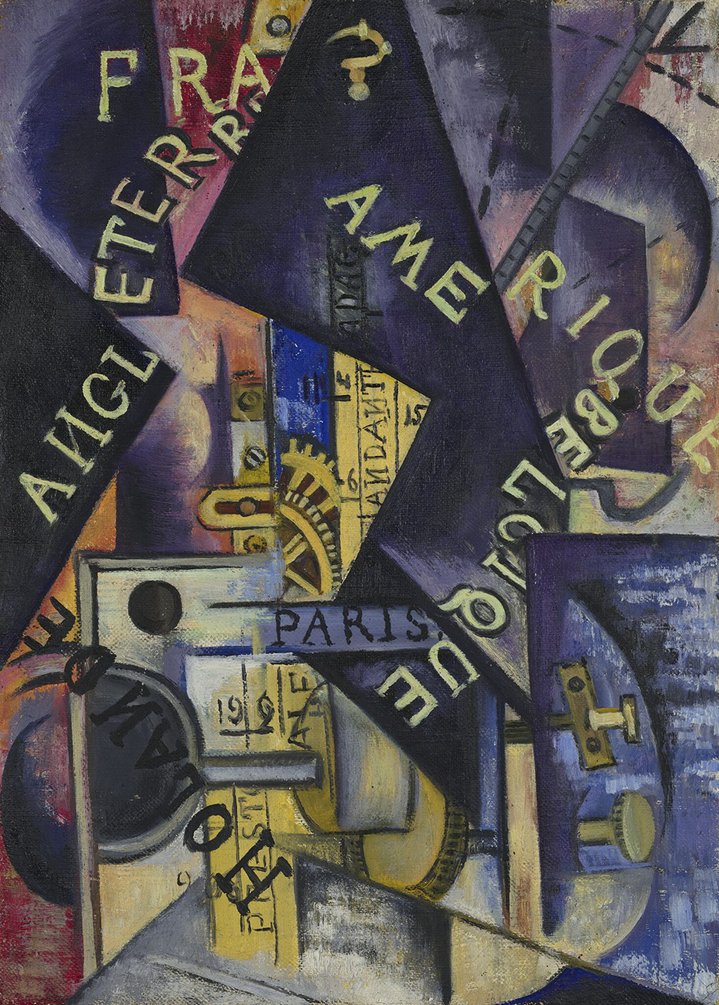

Such androgynous transformation of life on a path of commonality and the end of gender differences energises Olga Rozanova's art. The exhibition includes futuristic print editions created between 1913 and 1916 in collaboration with Rozanova's partner Aleksei Kruchyonykh. In the process of creating these lithographic editions, the artists switched roles. They fused different binarities in a common alchemical synthesis. Kruchyonykh as an artist made collages (the album ‘Universal War. Ъ’, 1915). Rozanova acted as a poet of borderline states. Researcher Vera Terekhina calls her writing oneiric poetry consisting of dreams, visions, and delirium. Within these poems, words and images, sounds and lines, rhymes and colours exchanged their essences. The masculine dictates of the word in the lithographed books capitulated with unmolested vowels, e.g. ‘lily’ becoming ‘e-u-yi’.

Mystical transformations through the erasure of clear boundaries and subject-object relations can be seen in the 1915 ´Playing Cards´, Rozanova´s most enigmatic series, known both as a cycle of coloured linocuts and in pictorial version. Bringing them all together from different regional museums in this show at GES-2 was a huge achievement. The main characteristic of Rozanova's cards is that they elude interpretation. We see lubok, but there is no simple irony and naive frivolity in the pictures. Art historian Faina Balakhovskaya believes that the images of Queens, Kings and Jacks encrypt portraits of Futurists and Suprematists, allies of Rozanova. However, there are precious few individual features in them. Each picture is endowed with a frenzied energy of transformation of the ordinary, the everyday, or the familiar. These Kings, Queens and Jacks seem to be agents of a new world in which the game of eternal transformation will become a force, the engine of life.

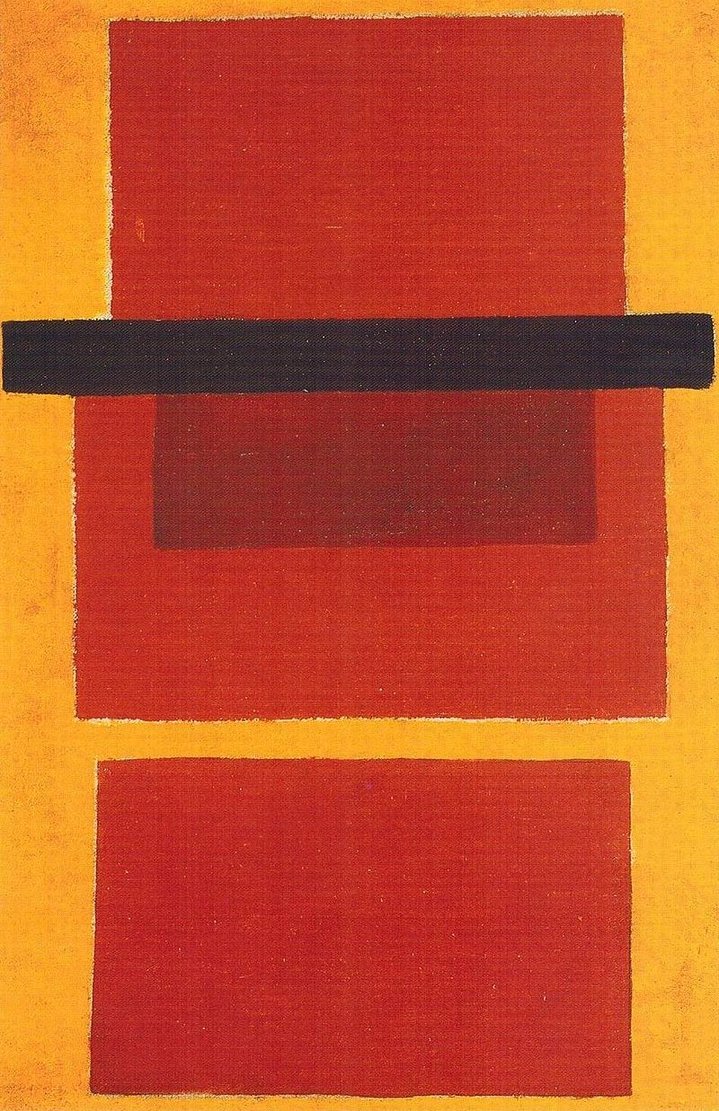

In the 2001 catalogue about the amazons of the avant-garde, art historian Nina Guryanova and art critic Ekaterina Degot make interesting reflections on overcoming binarity in the examples of the use of the words ´paint´ and ´colour´ by Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) and Rozanova respectively. Malevich advocated paint. Rozanova loved colour. Material, tool, technique, medium (everything associated with the word ´paint´) capitulated before the universal harmony of colour.

The capture of space using colour and planes defined the objectless world of Olga Rozanova's friends such as Malevich and other amazons of the avant-garde, Varvara Stepanova and Liubov Popova. Rozanova does not capture space. She atomises it. Numerous colour transitions create a musical vibration in universes devoid of any contradiction. Having lived a tragically short life, dying of typhoid fever in 1918 at the age of 32, Rozanova created her own theory of colour: tsvetopis´ or colour-painting. The principle idea was to convey the non-material essence of colour, to refuse any definition of subject. Any physical object or material is evidence of some limitation, a separateness in a binary world divided by the absence of love. The androgynous interpenetration of everything with everything defines the radiant palette in Olga Rozanova's final canvases. For Malevich, the ´icon´ of his Suprematism was the impenetrably deaf ´Black Square´, a veil that separates worlds. For Rozanova her ´icon´ was the ´Green Stripe´ of 1917, lent to the exhibition by the Rostov Kremlin Museum. After her death Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) wrote that the artist thought about creating colour with light. Rozanova foreshadowed Dan Flavin and other minimalists of the 20th century, who transformed space with neon tubes. Her ´Green Stripe´ is a volumetric colour light shining on a white field. As a sacred object of new art, it is placed in a glass container, a reliquary.

A Cup of Consonances: Approaching Rozanova

Moscow, Russia

10 November 2023 – 28 April 2024