Chagall without Chagall: Blockbuster Exhibition on the Jewish Avant-Garde in Moscow

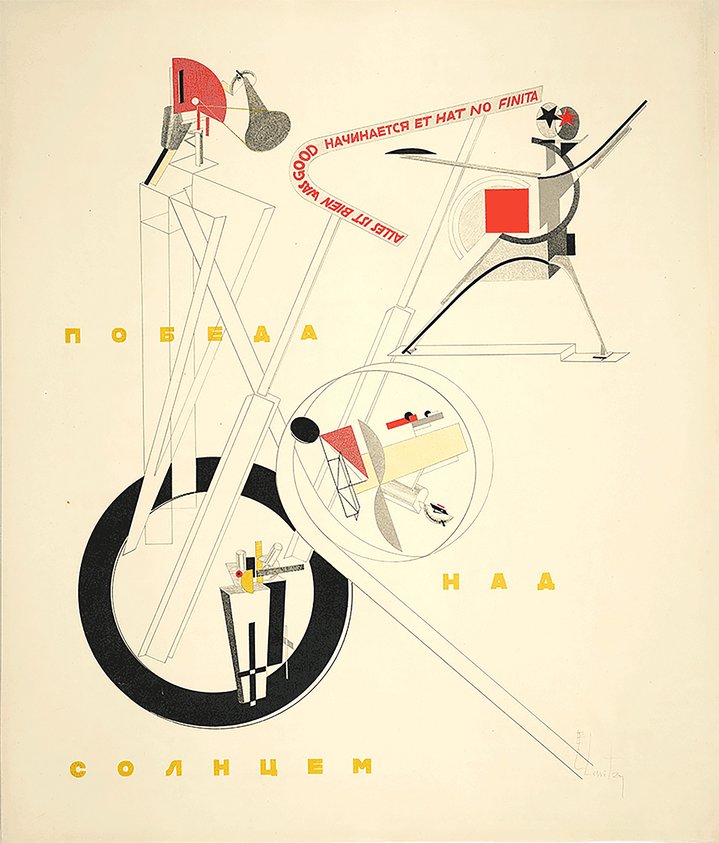

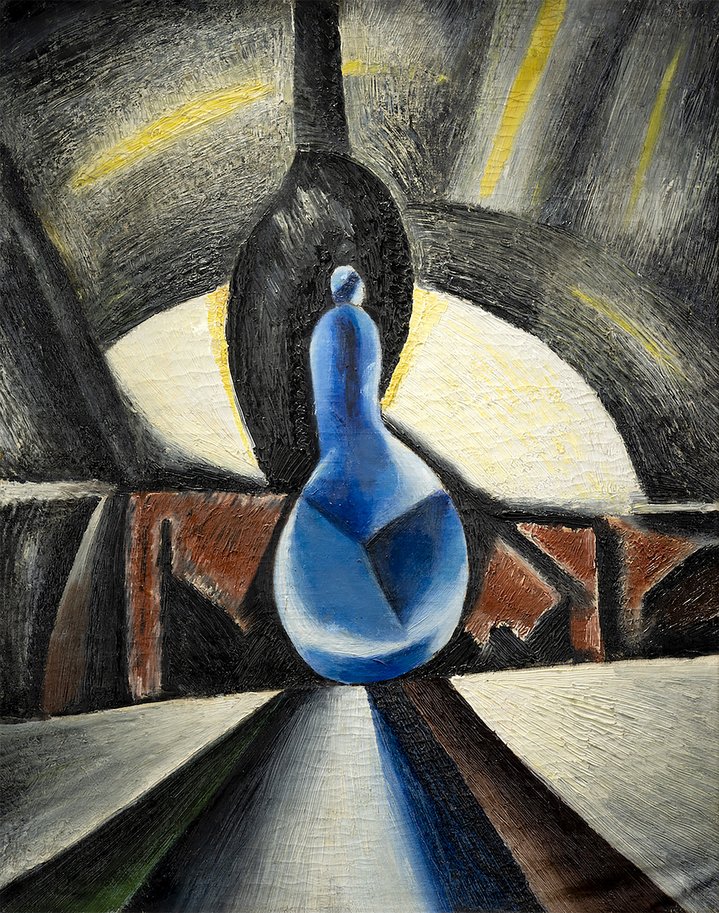

David Shterenberg. Still life with a candle, 1919-1920. Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts. Courtesy of Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center

An ambitious exhibition at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre in Moscow champions forgotten and overlooked artists.

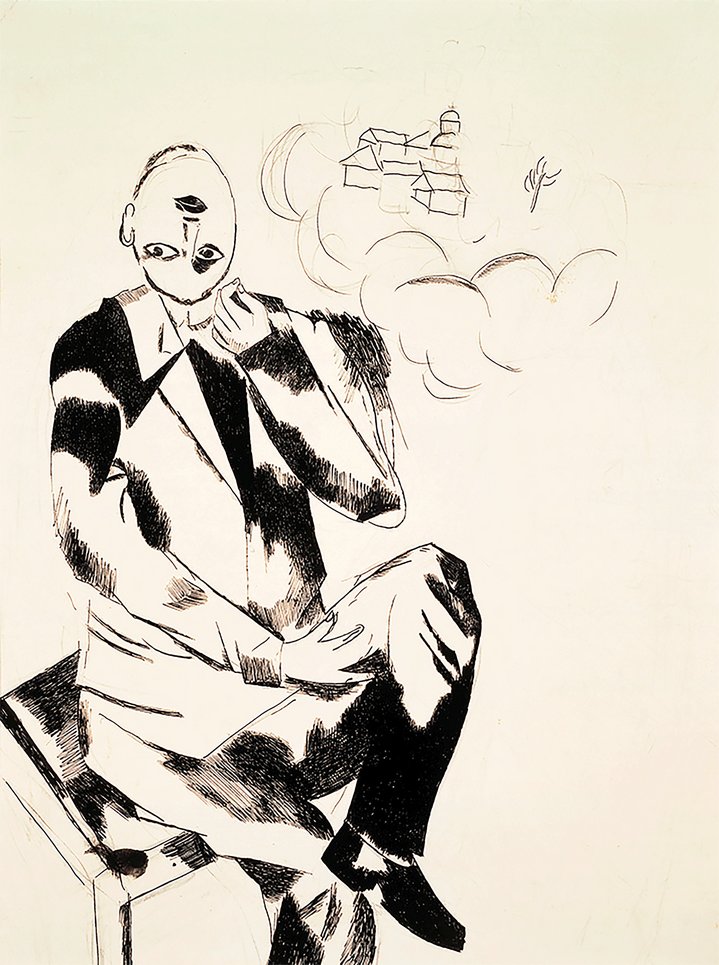

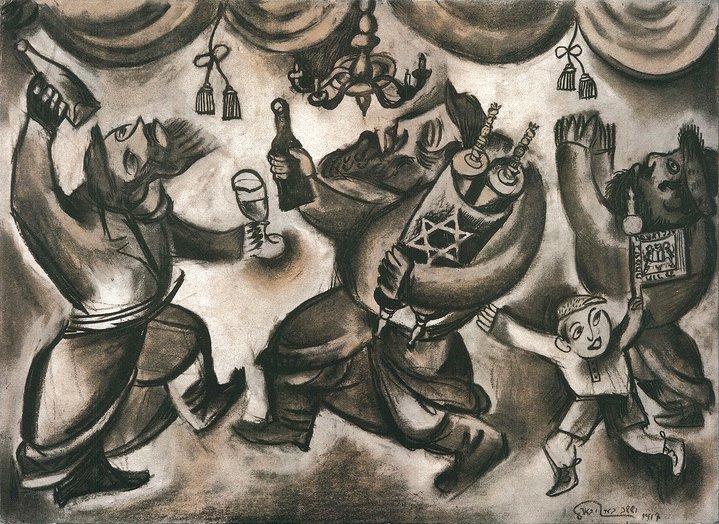

The exhibition ‘Jewish Avant-Garde’, curated by Kristina Krasnyanskaya, Maria Gadas and Svetlana Amosova is the first blockbuster show in Moscow this year. It brings together loans from museums across the whole of Russia, notably Tula, Saratov, Ekaterinburg, Nizhny Tagil, Yaroslavl, as well as major Moscow institutions: the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Pushkin Museum, the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, and the Museum of the History of Jews in Russia. Subtitled ‘Chagall, Altman, Shterenberg and Others’, of particular interest are these lesser known ‘others’, like Joseph Chaikov (1888–1979), Amshei Nuremberg (1887–1979) and Beatrice Sandomirskaya (1894–1971).

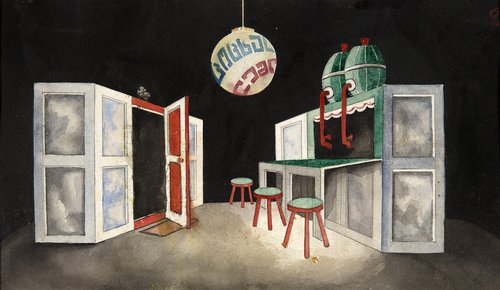

The fates of many of these artists are worthy of a novel, some of them of an ancient tragedy. Gersh Inger (1910–1995) was an amateur violinist who went deaf from typhus but continued to read sheet music until the end of his life. Nisson Shifrin (1892–1961), chief artist of the Soviet Army Theatre from 1935 until his death, assistant cameraman on the set of the second series of ‘The Great Citizen’ (1939), one of Stalin's most monstrous propaganda films, in which the "ordinary Soviet man" swears a great hatred for the enemies of Bolshevism.

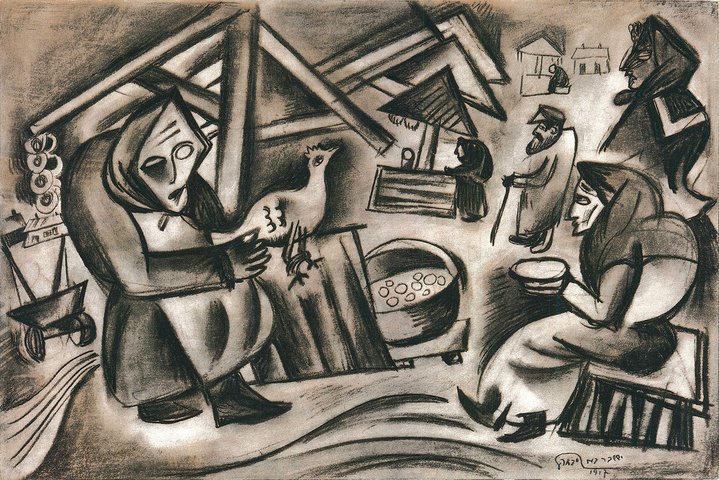

Abram Efros (1888–1954) wrote in 1918 that the “aesthetic revival” for the Jewish people "will grow out of the same two roots from which all world art of modernity grows – on modernism and folk art". This new exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Moscow proves this thesis. It is divided into four unequal parts: one focuses on decorative folklore, the other three consist of 20th century art. The problem is that these “two roots” have little to do with each other. If we understand the ‘Jewish avant-garde’ as art that is avant-garde in form and Jewish in content, then most of the artists in the show do not fit this definition. They are either too immersed in the everyday life of the Jewish shtetl to be deeply interested in form. Or they are too immersed in form, and there is nothing specifically Jewish in their formal pursuits, such as David Shterenberg (1881–1948), who tackled the problems of space, composition and texture common to artists of his era. Shterenberg is perhaps one of the most underrated artists of the Soviet avant-garde, because his real achievements involve the development of textures in painting, and they are quite difficult to see and understand from reproductions.

If Marc Chagall (1887–1985) had not studied the folk paintings of synagogues, he would not have become Chagall. It is thanks to Chagall that Efros's thesis of an "aesthetic revival" makes sense. The gap between "avant-garde" and "Jewish" in the exhibition is due to the fact that there are almost no original works by Marc Chagall in the show. Instead, viewers are greeted in the main hall by projections, in the spirit of multi sensory art experiences, although Chagall's works are not hard to find in Russian state and private collections.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) had African art. Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) had lubok and folk icons. The progressive Orthodox priest Pavel Florensky proposed to reinterpret Byzantine worship as gesamtkunstverk. The artists of Kultur Lige took as an aesthetic fact the synagogue and everything in and around it: Torah scrolls and amulets, festive flags and shtreimels.

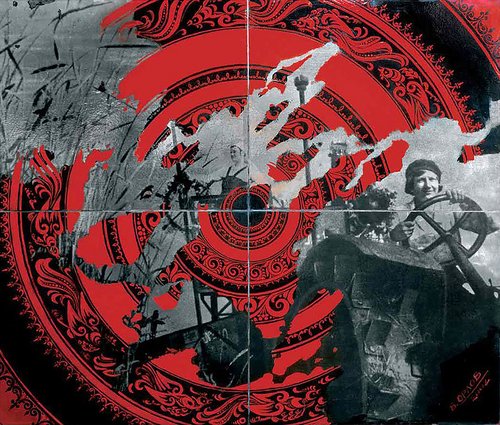

It is difficult to work with modernism at a time when a poetic illustration of the Song of Songs can be subversive. So this exhibition at the Jewish Museum, like any contemporary art exhibition in Russia, obviously had to choose between self-censorship and real censorship. But studying the Jewish avant-garde has never been easy in Russia. During the Soviet era, such a topic was perfectly fitted into the procrustean cliché of ‘bourgeois nationalism’, and therefore it only could be researched, bypassing dozens of obstacles. Even today, many details are not highlighted – for example, the relationship between Jewish artists and the Soviet authorities: the difficult balance between co-operation and opposition. For example, David Shterenerg in 1917 actually became the first head of Soviet art thanks to his friendship with the Commissar of Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky. But the same circumstance caused him trouble in the late twenties and thirties, when the "realists" Yevgeny Katsman (1890–1976) and Viktor Perelman (1892–1967) organised a persecution of the artist Shterenberg for "formalism".

This current show is unique in that it presents materials that have never been exhibited before, artists who rarely attract curatorial interest, and entire phenomena that so far have been analysed only marginally. For example, the figure of Joseph Chaikov, one of the founders of Soviet sculpture, is still poorly understood. Perhaps only Grigory Kazovsky, an independent researcher and author of the book "Artists of the Kultur Lige ", has described the world of the shtetl of the first half of the 20th century in its relation to modernism.

The exhibition is an important step in overcoming the late-Soviet schema, in which ‘Russian avant-gardists’ turn out to be Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Marc Chagall, and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), all artists who lived in different countries and whose native languages were different. While in the seventies and eighties the theoretical model of the ‘Russian avant-garde’ helped to overcome the dictatorship of Socialist Realism and the Soviet version of art history, today it is being justly criticised by post-colonial theory, and on the ruins of the schema of the ‘Russian avant-garde’ we find the ‘Ukrainian avant-garde’, the ‘Jewish avant-garde’, and so on.

The main paradox of the Jewish avant-garde is that, despite the enormous interest in it, it is rather poorly studied. The difficulty of developing this topic is that a serious researcher must speak at least four languages - Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian and Ukrainian. In addition, he or she has to work in the archives and collections of several countries located in the territories of the former Russian Empire, which today are often hostile to each other. The history of local modernism is still full of glaring blind spots. With this new exhibition, the Jewish Museum raises a whole layer of culture that still requires its own Vasari.

Jewish Avant-Garde. Chagall, Altman, Shterenberg and others

Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center

Moscow, Russia

5 March – 9 June 2024