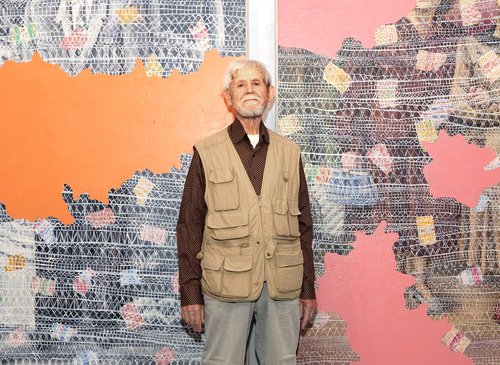

Vitaly Pushnitsky. Studios. Waiting. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Courtesy of Marina Gisich Gallery, pop/off/art and State Shchusev Museum of Architecture

Pushnitsky in Moscow: Self-Portrait of an Artist in an Imaginary Studio

‘Studios. Waiting’ a solo exhibition of works by Vitaly Pushnitsky has opened at the Museum of Architecture in Moscow. A joint project organised by the Marina Gisich Gallery from St Petersburg and pop/off/art based in the Russian capital, it explores the artist’s fascination with the metaphysics of studio spaces.

This summer in an unusual act of mutual collaboration, two independent Russian contemporary art galleries, Marina Gisich and pop/off/art have joined forces at the State Shchusev Museum of Architecture in the Russian capital to stage a solo exhibition of work by Vitaly Pushnitsky (b. 1967). The resulting project ‘Studios. Waiting’, curated by Ksenia Malich, is based on the theme of the artist’s studio. Across the several dozen artworks included in the show Pushnitsky presents artists’ studios in all their varied glory. There are studios that you might find buried deep in a forest, sitting inside some architectural ruins or at the more conventional end of the spectrum in dedicated rooms with large windows and minimal, purely functional infrastructure, as well as in libraries, museums, offices, flats, or in the garden of a dacha. The obvious conclusion that follows from such a diverse selection of imaginary creative locations is that artists can work anywhere. What is crucial is they have some impulse for some kind of activity there, since, as is well known to all who interact with artists, creative crises and blocks are far from rare occurrences. And in such cases, a purely mechanical maintenance of their skills provides salvation – for instance, even in depicting the studio itself.

In general, a studio can tell us as much about the artist who owns it as a flat tells us about the person living in it. The inhabitant of any space arranges it according to their taste, in accordance with their individual notion of what is useful, necessary, and, whilst not obligatory, what is important. At the very beginning of her curatorial text, Malich unambiguously points to this, speaking of the workshop as “a stage for intellectual performance, a diary of feelings and memory”.

Looking from this perspective, we can sketch an approximate portrait of Pushnitsky’s paintings. The artist often places plants in his hypothetical studios – both house plants in pots and wild plants that break through walls or floors (sometimes he even transfers the studios themselves into a forest). Such an invasion of flora might remind us of Boris Groys’s thought that one shouldn't expect beauty and the sublime from art. Nature provides us with both – even more than we need – and it is useless for an artist to compete with it and foolish to imitate it. Even if we make allowances for the fact that this thought is rooted in Groys's conceptualist background and might today have become somewhat outdated, there is still a kernel of truth in it: there are things weightier than any art that can be made and an artist must acknowledge the limitations of the results of their own activity. And it seems that Pushnitsky unconsciously accepts these rules, paying tribute to the grandeur of those forces which he can never tame or predict. Therefore, he grants them freedom in his works. And besides plants, other ‘aliens’ appear in his studios: stones, books, geometric figures – all demanding attention and living space, and registration.

Something else that catches the eye is how working spaces are organised, the distribution of tubes, jars, brushes, pencils, stretchers, frames, easels, paper, canvases, tables, stools, and so on. A strict order reigns in some studios where everything is neatly arranged and organised according to some system. Other artists find their studios turning into embodiments of raging chaos from day one: entering them, you cannot understand how anything meaningful can be created there at all, and there is simply nowhere to step amidst the monumental clutter. Judging by his works in the Museum of Architecture, Pushnitsky belongs to neither the first nor the second. With him, continents of structured zones are separated by seas of disorder. Moreover, one cannot say that these heterogeneous areas somehow clash with each other and there is no conflict; they coexist organically, balancing one another.

However, ‘Studios’ is not only a series of idiosyncratic self-portraits by Pushnitsky, but also landscapes and still lifes, and thanks to the presence of characters in some of his canvases – also domestic scenes, not without a touch of surrealistic dreamlike optics. Furthermore, the presence of ruins and other signs of the past distantly hints at the genre of historical painting – signs of specific epochs are cautiously woven into images which at first glance seemed torn from definite time and context. In short, his academic training makes itself known here: the artist literally can not limit himself to one single line; subjects and motifs sprawl in different directions, and the composition of each painting is oversaturated with details. One cannot say that Pushnitsky thereby generates chaos rather that he somehow balances on the edge of complete compositional collapse and amazingly always maintains his footing with confidence. This very light swaying to and forth and instability clearly appeals to him, for this creates some tension and intrigue in the works: it seems that nothing really happens in the pictorial space, yet simultaneously the viewer cannot help feeling feeling that something is definitely moving, acting, and speaking there – some secret and vital activity.

Although now the theme of studios is not such a widespread subject for artistic works, as a sign of everyday life it is surely the hottest topic imaginable: artists struggle for studios, seek options, happily acquire working spaces or dramatically lose them. Temporary ones, as in artist residencies that in major institutions seem to have multiplied like mushrooms after the rain, or permanent ones –studios become markers of an artist’s status, recognition of a stable position on the art scene. Their absence causes genuine suffering, frustration, disappointment in one’s own activity, and indeed in art as a whole. In this sense, the depiction of a studio turns out to be a tacitly taboo subject: if you have one – fantastic, if not – why twist the knife in this wound once more? Of course, Vitaly Pushnitsky’s project does not reveal this deep trauma inherent to the life of artists, and even less does it serve as a kind of therapy in these circumstances.

But probably amongst viewers from the ranks of, say, painters – especially those who have not settled so well in their profession yet, or have done so but with difficulty, work at home or are forced to roam through residencies for lack of their own corner – it might evoke an involuntary reaction: a mixture of melancholy and desire for possession. Here is how it can be: one can fantasise about the most whimsical studios, amongst stars, ruins, and trees, depict them from a metaphysical angle, but this detachment inevitably returns to the prose of life, one need only add a viewer concerned with pressing problems.

Vitaly Pushnitsky. Studios. Waiting

State Shchusev Museum of Architecture

Moscow, Russia

19 August – 2 November 2025