Arkady Petrov’s Personal Memories of the Donbass

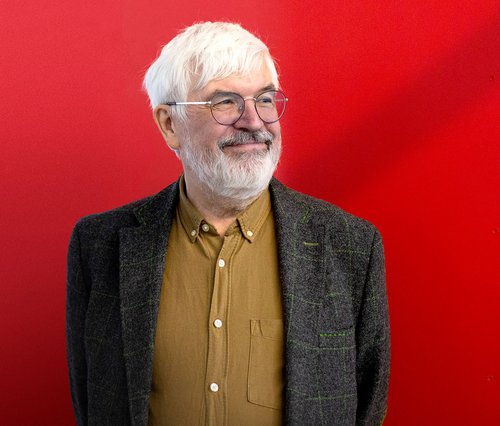

Arkady Petrov at 'Homo Soveticus' exhibition at pop/off/art gallery. Moscow, 2023. Courtesy of pop/off/art gallery

A solo exhibition of artist Arkady Petrov, whose multifarious work inhabits the boundaries between conceptual art and Sots Art has opened at the pop/off/art gallery in Moscow.

Arkady Petrov (b. 1938) was born and raised near New York City. But this is not New York on the Hudson rather the oneclose to the town of Gorlovka in Ukraine. You might have only heard about that New York if you have been listening to reports from the Russian-Ukrainian front. Community housing for miners in the area was often named after world capitals. Some artists move away in mind and spirit from the little homesteads of their youth, not Petrov.

Arkady Petrov was born and grew up in a mining community ‘Komsomolets’ in the Stalin region of the USSR. “It was the end of the world,” he recalled in a recent interview to The Art Newspaper Russia. “There was nothing: no theatres, no greenery, just mines and dust. I always wanted to paint, but there was no one there who could help me. There were crooks, gypsies, gangs and extreme poverty.” As an adult Petrov often returns to his childhood in his dreams, and he regularly visits this country of big coal with its bygone world. The region has been called Donetsk for several decades, becoming the Donetsk People’s Republic in 2014, the mine closed down and the community is falling into decay, although memories cannot be erased.

“I wonder how it is painted?” an artist asks at the opening of Petrov’s exhibition peering at one of the paintings hanging on view.

“It’s on an oil cloth. The reverse gives an interesting texture,” I say.

“I must try that myself!”

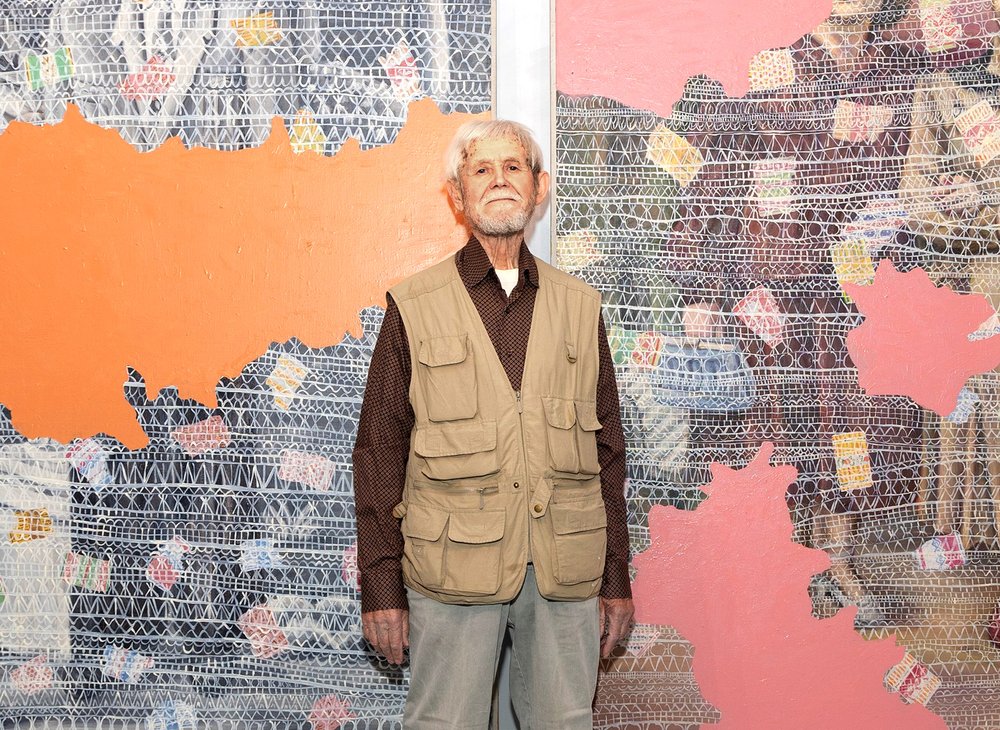

This anecdotal conversation is evocative of Petrov himself who is a master of appropriation. It is challenging for critics to describe his work because it is constantly changing. This latest exhibition at pop/off/art gallery in Moscow makes a brave attempt to penetrate into the world of this artist, who has been mentioned in association with perhaps every single major current or movement in Soviet and post-Soviet art over recent decades.

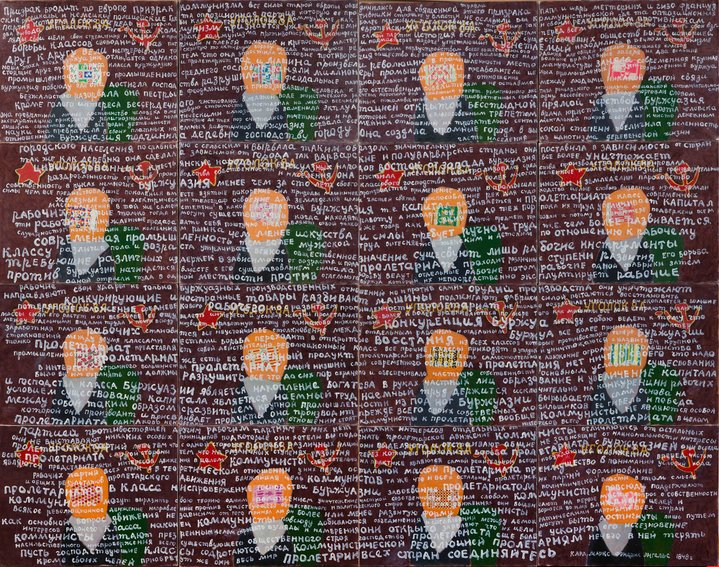

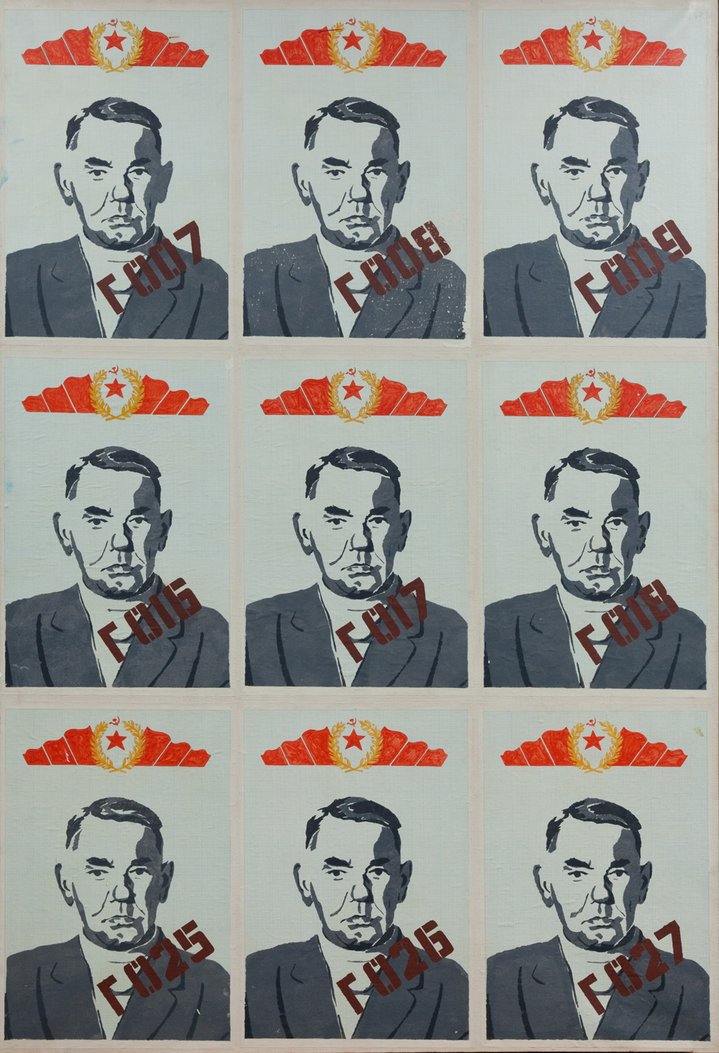

His 1971 painting ‘Change’ is a radical example of the severe style, closer to the grim realism of the thirties rather than the Soviet romanticism of the sixties. Two decades later, his 1990 ‘Little Cabinets’, a work in the style of ‘Moscow Romantic Conceptualism’, echos Eduard Gorokhovsky (1929–2004) for its serialism, reliance on photography and sudden intrusions of dots that look like enlarged raster.

Gallery owner and art critic Sergey Popov presents an unusual experience for gallery visitors in Moscow where he leaves it up to the public to talk about the artist. It is as if Arkady Petrov is a soloist in an unharmonious chorus. His 2019 work ‘Rest’, a nude amidst patches of colour is juxtaposed with the colour smudges of abstractionist Yuri Zlotnikov (1930–2016). ‘Red Flag’ is juxtaposed with photographic compositions by Vladimir Kupriyanov (1954–2011). A sculpture from the ‘Bread’ cycle by Anatoly Osmolovsky (b. 1969) is placed between two paintings by Petrov. This approach creates a contextual argument.

This is the seventh solo exhibition of Petrov’s work at Popov's gallery. The artist has been working with him since the middle of the noughties when the gallery was founded. In all the previous exhibitions Popov curated the show keeping a sense of one style, in which the artist was working at any one time. Each show was very different from the last and if you were to put them together it would seem as though they were exhibitions by different artists, not one.

‘Red Flag’ (2000–2014) is a portrait of a chubby character on skinny legs, either a hunchback or a teenager with special needs. A red flag hangs next to him in the ether. All around is an emptiness that breathes through the intrusion and sprawl of grey and white strokes across the rough surface. An artwork of extreme psychological tension, where the background functions as an independent work, and the protagonist is both inserted into the background and grows out of it he is painted in the same palette as the space around him.

Despite the multifarious aspects of his style, Petrov has found his own type of character, a little man with inverted nostrils and a flattened head, it has become his hallmark, a bit like egg-heads are for Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021). "Why don't I paint beautiful people? It's not that I don't like them, they're just not mine," he explained in an interview to The Art Newspaper Russia. A whole family, a man in a cap, a fat-legged wife and a baby in shorts, different and identical at the same time are depicted in his 2017 painting ‘Miners’. It’s an image of class, scary and comical, anti-naturalistic and recognisable, touching and haunting, like the traditional folk song: "I was a brave horse-driver, My dear mummy, I was killed in a dark mine, And you stayed alone".

Images of mines and miners, the atmosphere in the miners’ barracks act as binder holding Petrov's works together. His sense of place of origin is expressed through a series of memories, which he reproduces in one way or another using different styles, like an actor in Stanislavsky's system, whether it is crime or romcom. Petrov’s early, brutal painting style is different from what he does today. In those early works the world of coal is depicted as a grey-brown never-ending frieze of workers and wagons, steam engines and workshops, a conventional gloomy zone painted not according to the pictorial canon of Socialist realism, and emotionally closer to Oscar Rabin (1928–2018) than to the official optimists

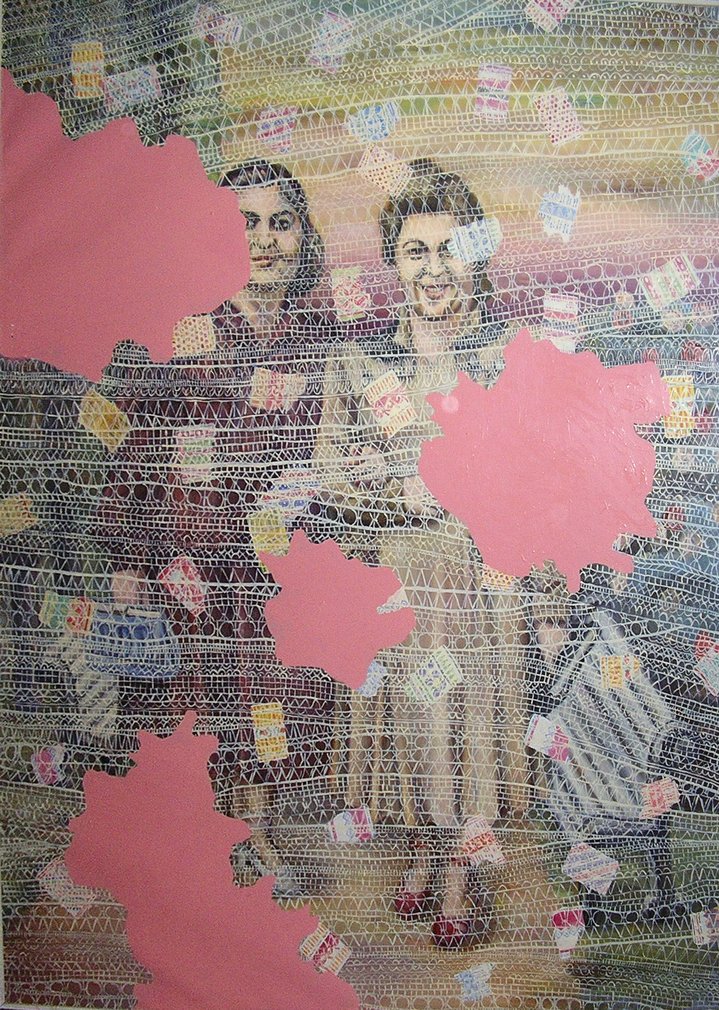

Petrov's works from the mid-seventies reveal a very different kind of mood where there is a focus on colour, nostalgia in kitsch hues. He is inspired by keepsake photo cards, holiday postcards, wedding albums, and then in the eighties, the brighter the colours, the wider the range of his fascination with mass culture. He becomes interested in advertising signs, record covers, street posters. Petrov creates his own gallery of portraits of pop singer Alla Pugacheva, long before the artist duo Alexander Vinogradov (b. 1964) and Vladimir Dubossarsky (b. 1964). The grotesque and eros flourish in the same territory, receiving their highest expression in his 1981 painting ‘Alla Pugacheva and Arkady Petrov’, where the artist depicts himself together with the most famous Soviet pop diva as a pair of lovers in paradise – this is years before Jeff Koons' (b. 1955) works dedicated to Cicciolina.

In 1988 Petrov became internationally known after Sotheby’s legendary Moscow auction of Soviet Modern and Contemporary art. His work ‘Dancing. A Brass Band Plays,’ was sold in that auction, although in the shadows of the much more successful sales of Aleksander Rodchenko (1891–1956) or Grisha Bruskin (b. 1945). Petrov thus found himself caught up in the ‘Russian wave’ of the late eighties and early nineties, which led him to participate in band projects across America from Washington DC to Little Rock, Arkansas. That wave, however, quickly fizzled away to nothing for him, as it did for most of those swimmers. ‘Bet on Glasnost’ turned out to be more of a political bet.

Having received his 15 minutes of fame, Petrov soon sank into obscurity. Never truly a conceptualist, nor a Sots artist, nor a non-conformist, in many ways he resembles all of them. Appealing to the emotions rather than ideas, his 1995 ‘Miner with a Jackhammer’ is a gloomy persona, grey against a grey background. In the nineties, conventional figures became his new style, reflecting the traumatic degradation of the working class.

Over time Arkady Petrov has become the visionary of a non-existent country. It comes back to him either in a pack of cigarettes ‘Shakhtyorskie’ (1987–2006), which materialises into a large-scale painting, or in a handshake without characters in the 2004 painting ‘Remember Our Meetings’, where only a solemn gesture of two hands, male and female, united, is what remains of equality and brotherhood.

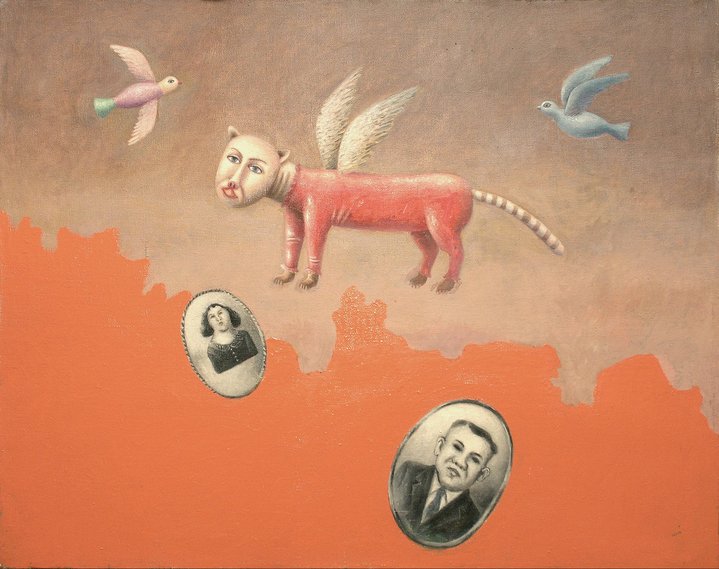

Petrov's paintings refer not to reality, but to memories. They do not reproduce the exact order of things, but as in the depths of memory, only the most important things are stored, which appear on the motionless backdrop of a canvas. These characters are only loosely connected with the background, they are as if suspended in airless space or superimposed on a plane. His paintings are dream-like. They are visual shards from the depths of memory.

Memory impressions of Donbass (Donetsk region) are moulded into his paintings. Ghosts of sensations lie on the canvas. Petrov has a kinship with naive art, it is not superficial, but an internal closeness. In his paintings, the voice of the inner child breaks through, a child who does not see barracks or poverty, impenetrable mud or cows' dung, but embroidered doves, rugs with swans and the endless blue sky, under which the gaunt and squat heroes of the dungeons live. In contrast to the dry and hollowed-out world of Ilya Kabakov's (1933–2023) characters, Petrov's miners are rough, uneven and alive. Petrov's paintings are like dreams come true.