Our Avant-garde: Punin’s Epitaph at the Russian Museum

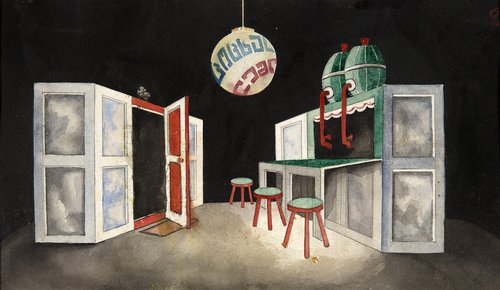

The Avant-Garde. The Great Experiment of Russian Art. Exhibition view. St Petersburg, 2025. Photo by Sergey Nikolaev. Courtesy of the State Russian Museum

A major new exhibition at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg called ‘Our Avant-Garde’ transforms a dozen vast halls into a compelling narrative about early 20th century revolutionary Russian art featuring hundreds of best loved masterpieces of the era.

Asserting its status as the best collection of Russian avant-garde art in the nation, the State Russian Museum has arguably put together its most coherent and all-encompassing exhibition on the subject. It was not until as late as the 1980s that the Russian avant-garde finally earned its long-deserved place hanging on the hallowed walls of the nation’s leading museums. A whole century passed before its inherent artistic and cultural value was established beyond question and the avant-garde became what it is today: a universal visual language.

The exhibition is spread out through an enfilade of thirteen separate spaces and consists of four hundred paintings, works on paper and sculptures which collectively tell the story of the time in which it was created and the artistic ideas to which it gave birth. Although the Russian language title of the exhibition which directly translates into English as ‘Our Avant-Garde’ (curiously translated into English on the museum’s website as ‘The Avant-Garde. The Great Experiment of Russian Art’) was chosen by the directors of the museum and not the curators any toxic political nuances behind this title remain hidden away in the backroom, because there is no obvious attempt in the exhibition to assert Russian primacy over the avant-garde nor any argument for the special Russianness of artists with Ukrainian roots, of whom there are many in the exhibition.

If you look for any polemics at all in the title and concept of ‘Our Avant-Garde’, then this massive panorama of revolutionary art which the State Russian Museum is offering is remarkably different from the vision behind the 2017 London exhibition ‘Revolution. Russian Art: 1917–1932’ curated by Natalia Murray at the Royal Academy of Arts. That said, both exhibitions share a common starting point in the figure of Nikolai Punin (1888–1953), an outstanding Russian art historian, art critic, curator, teacher, and leader of everything new in art, who tragically perished in a labour camp at the end of the Stalinist era. As early as 1921, Punin created the Museum of Artistic Culture in Petrograd, which became the first ever state collection of avant-garde art and later, in 1927, he curated a fundamentally new type of exhibition in the Russian Museum, a historical initiative which lies behind much of the current show. Kazimir Malevich's (1879–1935) portrait of Punin (1933) serves as its visual epigraph to ‘Our Avant-garde” as it did in 1927. The initial working title for the current show was ‘The Russian Avant-Garde. A Guide’, which refers to an exhibition guide written by Punin back in 1932.

Due to the exceptional holdings of the avant-garde in the State Russian Museum, the majority of the works of art are already well-known in St Petersburg with only twenty-six works on loan from other museums. Although ‘Our Avant-Garde’ consists of mainly first-tier names, it incorporates recent scholarship honed through other museum shows it has staged over the past decade. These include ‘Flat No. 5’ (2016) about the history of the Petrograd avant-garde from 1915–1925; ‘Art into Life! 1918–1925’ about propaganda and applied art in Petrograd (2017); ‘Expressionism in Russian Art’ (2018) and ‘Union of Youth’, (2019) dedicated to the artistic association of 1910–1914. Research undertaken by Alisa Lyubimova, Irina Karasik, Irina Arskaya, Natalia Kozyreva and their colleagues at the museum formed the basis of the current exhibition.

‘Our Avant-Garde’ is a first collaboration between the State Russian Museum and renowned Russian architect, contemporary artist and curator Yury Avvakumov (b. 1957) who has enjoyed a long career of exhibition design, starting with the ‘Lyubov Popova’ (1889–1924) exhibition at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in 1989. Avvakumov has always had a deep interest in the Russian avant garde which lies at the heart of his artistic vision. As an exhibition designer, he prefers to display the classics of the Russian avant-garde without any special design tricks, rather for him what is most important is “the comfort of the viewer”. Each of the thirteen separate halls has been given its own colour scheme designed by Russian abstract artist Alyona Kirtsova (b. 1954) – who is also Avvakumov's wife.

The current exhibition marks a significant break with the past. Over the past fifteen years without interruption, Russia’s pioneering avant-garde art has been displayed in a long enfilade of neoclassical style halls at the museum with the same overhead lighting based on one simple principle: that every artist is a heroic personality. The problem with this rather romantic approach is that it removes the context from the artists and for exhibition goers it is unclear how fundamental ideas around form and plasticity in the arts developed at the time. Avvakumov has in the past said how he dislikes linear structures in art exhibitions and here he decisively rejects what he calls “chronological tedium”.

‘Our Avant-garde’ may eventually become a permanent display at the museum. It is not simply a historical narrative proceeding from Cubism and Futurism through Cézannism and Primitivism to Abstraction, but also a captivating story about life consolidated into a brief period of exceptional artistic development, where everything happened in a futuristic fashion: non-stop, quickly, dramatically, and even almost simultaneously. Artists actively formed various associations and were exceptionally close; the first hall of self-portraits and portraits of cultural figures of the era is full of ironic cross-references: poet Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966) and composer Arthur Lourié (1892–1966) who were close friends look at each other from portraits painted by Nathan Altman (1889–1970) and Pyotr Miturych (1887–1956) whilst the gazes of Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) as ‘The Sailor’ (1911) and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) in his 1933 ‘Self-Portrait’ are pointedly facing in different directions.

Avvakumov approaches exhibitions as construction and perhaps unsurprisingly he singles out the constructivists among all avant-garde groups as his spiritual heirs. As with Punin, Avvakumov’s true hero is Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), and a major hall where the enfilande turns a corner is dedicated to this artist alone. It is painted in white, and a model of his famous unrealised tower ‘Monument to the Third Communist International’ in the centre casts a shadow on the wall. The Russian avant-garde owes its existence to two artists with Ukrainian roots who valued their national identity – Malevich and Tatlin, who starting from different points of the artistic compass made discoveries which are crucial to our full understanding of modernity. The avant-garde was destined to overcome any boundaries from aesthetic divisions to state borders and to move beyond all dimensions through abstraction.

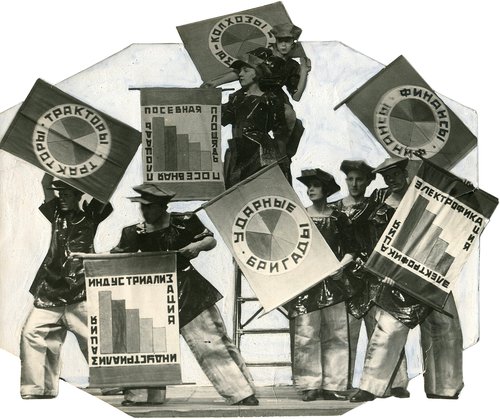

In Avvakumov's engaging display, visitors follow the destiny of each artist through his or her various periods of creativity. There are some protagonists who transition from one space to the next including Olga Rozanova (1886–1918), Ivan Puni (1890–1956) and Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962). And of course, Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935),whose works accompany the viewer from the entrance of the show to its finale, where you see a slide show with costume sketches for the production of ‘Victory Over the Sun’ and there is a real vintage fragment of this Futurist opera created in 1913 by Mikhail Matyushin (1861–1934) and Alexei Kruchenykh (1886–1968). The many juxtapositions, collisions, and intersections which the curators have carefully set up throughout the exhibition are what really bring this show and the collection of the Russian Museum to life. Paintings by Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) appear in sections about the ‘Union of Youth’, Abstraction, and Expressionism, and finally they fill an entire hall which lays out the artist's own idiosyncratic, so-called ‘analytical method’. Through his futuristic ‘Aviator’ (1914) and primitivist ‘Reaper’ (1912), Malevich emerges into the total abstraction of his iconic ‘Black Square’, and ‘Cross and Circle’ and then finally closes with a hall of sublime post-suprematist works from his peasant cycle.

It has become common recently for major exhibitions in European and North American museums to carry a curatorial statement and, loyal to one particular academic school or the other to inevitably set up a battle of concepts. A certain lag in Russian intellectual trends has played a positive role here because in ‘Our Avant-garde’ what is of greatest importance is fundamentally and frankly the best way in which to display the works.

As Avvakumov refers to the staggering number of artworks on display adding that “it is structured by movements and groupings, enhanced with texts, so the main thing is not to distract the viewer with anything else”. Indeed, contemporary art and curatorial concepts are secondary when interacting with art that was first displayed within the walls of a museum by gigantic personality like Nikolai Punin. Following in his footsteps, the new exhibition breaks with museum convention and walks us through all the freedom and complexity of living artistic form.

The Avant-Garde. The Great Experiment of Russian Art

St Petersburg, Russia

21 June – 1 December 2025