Avant-garde vocabulary

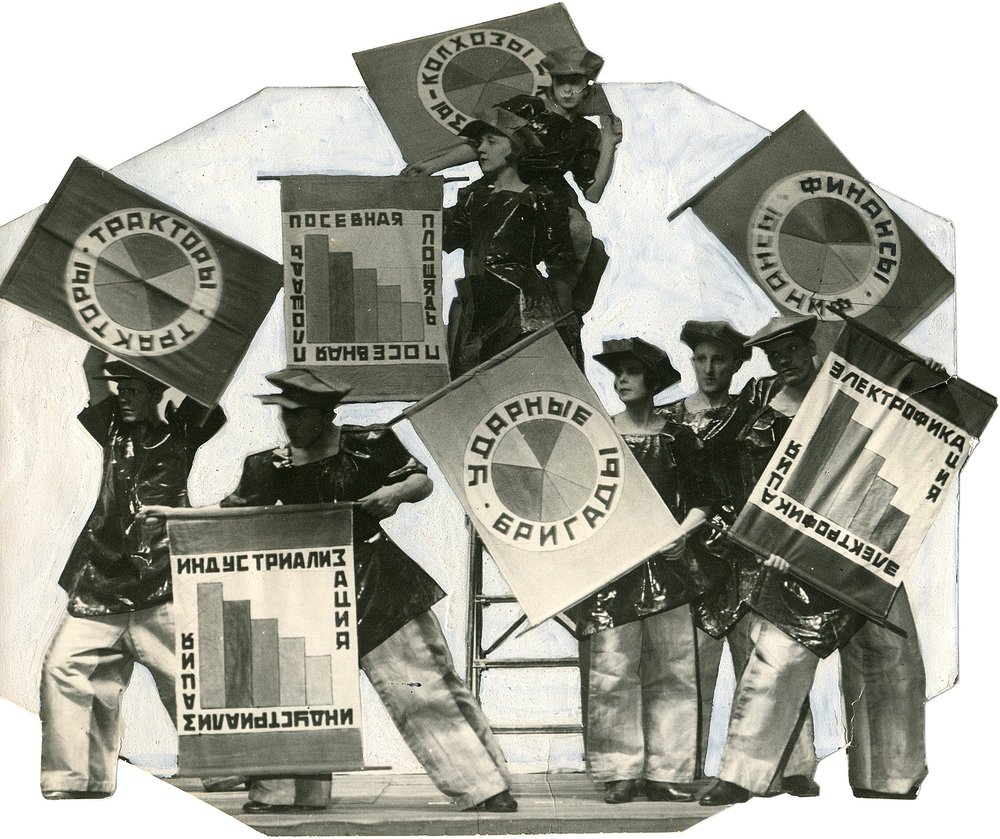

Illustration-photomontage for the magazine 'Blue Blouse', 1924–1930, Moscow. Photographic paper, silver-gelatin print. Courtesy of A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum

The exhibition ‘Logos: Voice of Constructivism’ has opened at the Moscow’s Zotov Centre. It will run until 6th of August and is accompanied by educational programmes on the aesthetics of the Soviet avant-garde from the cinema to advertising.

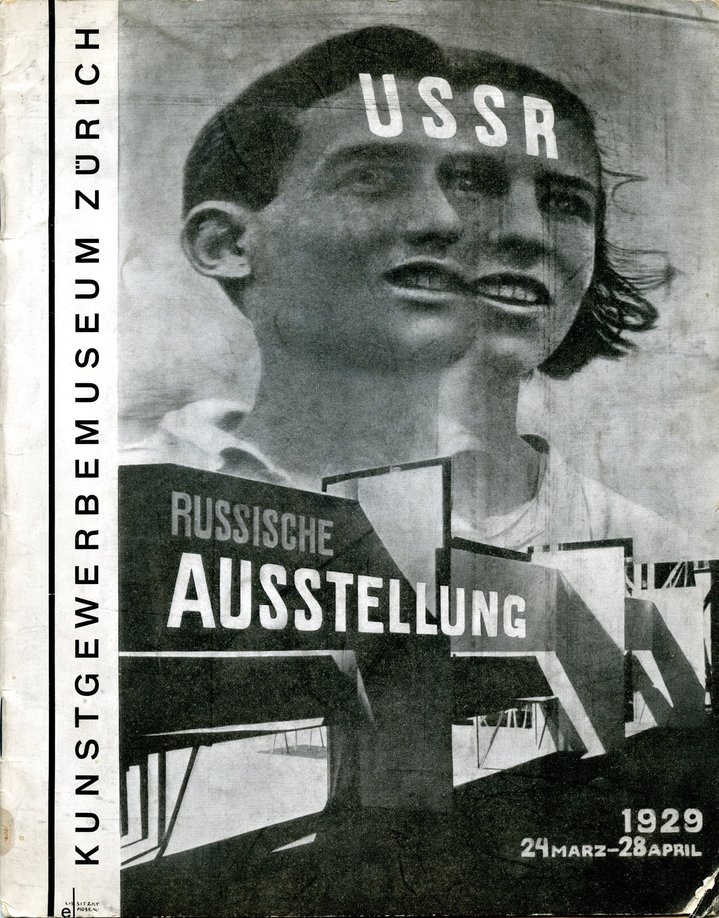

Notions and concepts around the aesthetics of constructivism lie at the heart of this educational encyclopaedia of a show which is divided into four thematic sections: ‘The Living Word', 'Agitprop', 'New Optics' and 'New Media'. Spread over the two floors of this repurposed bakery factory, architect Anna Zamriy has installed lightweight structures made of plywood which resemble pavilions. She evokes the spaces of the original avant-garde exhibition pavilions designed by Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), El Lissitsky (1890–1941), the Vesnin brothers Alexander (1883–1959), Viktor (1882–1950) and Leonid (1880–1933). Wide windows inside the wooden walls give spatial dynamics to the whole circular enfilade. Illuminated adverts, Anton Lavinsky's (1894–1968) restored reading-room and Gustav Klutsis's (1895-1938) `Radio-orator’, bring alive the once great experiment.

In the circular rooms on both floors, architect Anna Zamriy, curators Polina Streltsova, Ekaterina Lavrentieva and Konstantin Dudakov-Kashuro displayed written texts which help to elucidate the meaning of the four main sections. The texts on plywood in the exhibition spaces are alongside exhibits gathered from more than thirty museums and private collections. The sections and chapters comment on the theme of Constructivist aesthetics and how they worked with words, ideology, propaganda and advertising. In the exhibition these themes are dealt with in an impressive manner through the participation of precious objects, including rare books, paintings, drawings, models and photographs. Credit and praise are due to the curators for the reconstruction of the Tenth State Exhibition of 1919, 'Unpretentious Creation and Suprematism'. This exhibition staged the drama of the confrontation between the two leaders of the avant-garde: Rodchenko (who spoke under the pseudonym of Anti) and Malevich. These two poles or two points on the colour scale. Rodchenko painted black on black. Malevich painted white on white. Rodchenko's wife Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958) combined painting and sound in colour and graphic art, thereby anticipating the intermedial art of the present day.

In the sections of the exhibition dedicated literature and books, the Constructivists sit comfortably side by side with the Futurist poets Alexei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov. And there are even drawings and diagrams by the Symbolist poet Andrei Bely for his 1916-1922 poem ‘Glossolalia’: a theory of the universe of speech, a cosmogony of speech sounds. With such a wide-ranging panorama of speech experiments of the 1910s, it is not very clear why the most repressive version of the verbal dictate of simple and banal orders, which became the policy of the Proletkult of the 1920s and mutated into the totalitarianism of the 1930s, won out in the end. Two wordess installations of contemporary artists Platon Infante (b. 1978) and Vladimir Abikh (b. 1987) (in the latter’s work the letters are present but barely discernible) are hardly visible, almost drowned in all this rough sea of text.

The detachment with which the curators of the show approached the task, giving no space for a personal viewpoint or interpretation of the material, and their desire to show everything objectively and honestly, and to leave people to their own devices to figure it out, is understandable in today's ideological conditions. Yet this crumbling alphabet, the vocabulary of the avant-garde experiment, and the encyclopaedic articles about it, once again deprive the material of the most important thing: the strength, the energy, the polemicism contained in the experiment. The themes of agitprop, new media, and advertising were all leitmotifs of the era, since Сonstructivism emphasized the inclusion of every citizen of the USSR in the general machine, the mechanics of life as a part or a machine of a giant construction company or a plant. That is, ideological zombification, depersonalization for the sake of uninterrupted operation of the lifecycle production conveyor defined all signs of the style: both the chopped font of screaming, psychologically striking advertising modules, and the ribbon glazing of factory-kitchens.

The Futurists, non-Objectivists and Constructivists believed that their ideas and images were part of the living design of life in the here and now, and they were not to be archived in museum showcases. We can learn from the mistakes they made. Today's view and appraisal of constructivism with its logos, voice and dictatorship is necessary in order to respect the design thinking of the avant-gardists themselves, for whom museification is deathlike.