Komar and Melamid: The Subjunctive Moods of History

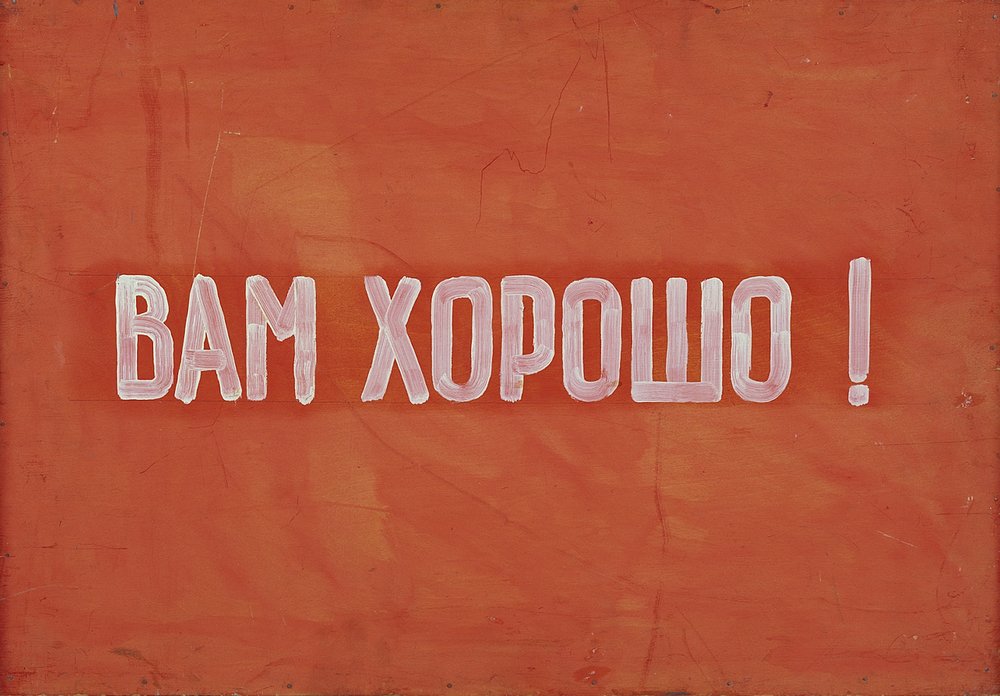

Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. You Are Well! from the series 'Sots Art', 1972 © Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid

The Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University honours the founding fathers of the Sots Art movement with a largest-ever U.S. retrospective of this legendary artistic duo who both defined the zeitgeist of the Soviet underground and had a bounteous second bloom in emigration.

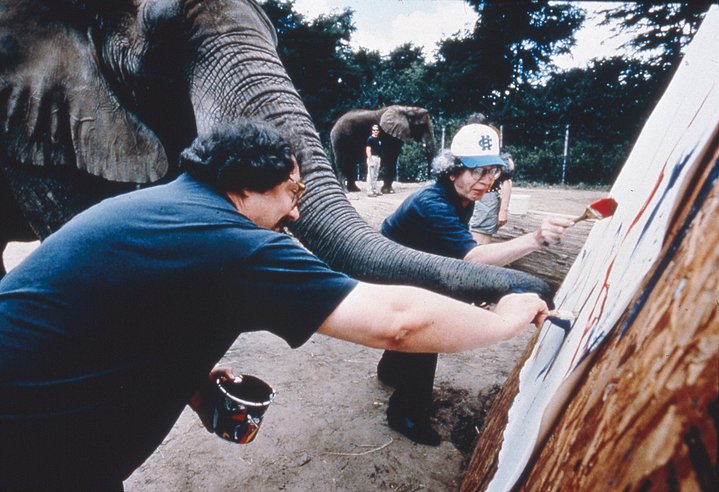

Spanning three decades, culled from Komar and Melamid’s vast and eclectic body of work, this mega exhibition tucked away in New Brunswick features over 100 artworks, including paintings, photographs, etchings, installations and documentation of key performances and early exhibitions dating from 1972 till 2003. Adding to the sense of occasion there are also two satellite exhibitions of recent artworks done by Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945), who since 2003 have been working solo. Komar’s new works are charged with politics and metaphysical reflections while his former art partner engages in a whimsical dialogue with The Incoherents, a late 19th century anarchic group of French writers and artists.

Contrary to the old adage, “History does not tolerate the subjunctive mood,” the art of Soviet-born New York-based American conceptualists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid thrives in the subjunctive moods of history exploring situations which express wishes, suggestions, demands, or desires. In K&M’s case, it is not only the past but the present which is interrogated in their work.

The exhibition’s title A Lesson in History feels apt. Komar and Melamid’s work has long been included in art history textbooks, dictionaries and encyclopedias, and a staggering volume of scholarly papers, dissertations, treatises, and stand-alone pieces of art criticism have been written on their multi-stylistic oeuvre both in the U.S. and internationally. One might say that any lesson on the history of art would be somehow just a dash incomplete without a chapter on Komar and Melamid, the ‘children of Socialist Realism and grandchildren of the Avant-Garde’ (Komar&Melamid, Death Poems, 1988) who, upon gaining notoriety in the former USSR and eventually relocating to the West in 1977, against all odds became two of the most talked-about artists in the U.S., darlings of the nascent New York downtown art scene in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Of course it is history as well as the history of art, that looms large in the duo’s diverse and inventive oeuvre. You feel it in the recurrence of political figures from the 19th and 20th centuries represented with an irreverent parodic twist; the latter evidenced by Komar and Melamid’s appropriations of classical compositions and occasional hijacking of salon painting settings. They loved to quote from 18th century landscape painting as seen in their unsettling cluster of dystopian works titled ‘Scenes from the Future’ exhibited in one of their first (of many) shows at the Ronald Feldman gallery and presented now at Zimmerli.

Navigating this impacted terrain of alternative history what do we find? As the duo’s pieces from the post-Art series created five years prior to ‘Scenes from the Future’, show us: nothing more than burnt or mangled canvases of Lichtenstein, Warhol, Wesselmann and Jasper Johns. All things must pass, Komar and Melamid remind us, echoing Ecclesiastes in the Post-Art series which curiously was created before the artists left the former USSR. Time was merciless to Renaissance frescoes; masterpieces of 19th century painting became collateral damage in human conflict of WWII; more recently ISIS detonated the Temple of Bel in Palmyra, and maybe little or nothing will remain of the great masterpieces of modernism. Komar and Melamid’s own work was destroyed in 1974 upon orders of the Soviet authorities while the artists were assaulted by the plainclothes militia men during the infamous “Bulldozer” group show in Moscow’s Belyaevo park.

Back to the present, the exhibition at Zimmerli has been superbly and sensibly curated by Julia Tulovsky, organized chronologically, and divided into two sections. The first showcases K&M’s early nonconformist period with signature pieces of Sots Art, a Soviet blend of Pop Art, Conceptual art and Dada. Conceived, named, and launched by Komar and Melamid they appropriated and personalized Soviet-era ideologemes such as banners, slogans and posters, putting an ironic spin on these propaganda signposts that the State ubiquitously deployed to address and control its subjects. If the white-letters-on-red Brezhnev-era banner ‘Our goal is Communism!’ is reproduced and then signed by Komar and Melamid, how seriously is one to take this re-contextualized imperative now that it is subjective? What to make of the artists who inscribe themselves into a governmental body dispensing directives to be followed? In other words, unlike Pop Art which foregrounded the oppressive presence of advertising as part of Western consumer culture, Komar and Melamid satirized the vacuous overabundance of communist propaganda, an artistic practice which, in retrospect, seems more politically potent than Pop Art as it purported to subvert the latter. “Having lived in New York for many years now,” Komar observes, “I see western advertising as ‘consumerist propaganda’ and Soviet propaganda as ‘ideological advertising.’” (The Art Magazine, translated by Jamie Gambrell).

Unruly theatricality replete with fake identities abounds in the first part of the exhibition which evokes the duo’s trademark carnivalesque cheekiness. The viewer has a glimpes into the ‘documented’ lives and times of two fake artists: a freed serf called Apelles Ziablov, who discovered abstract painting in the late 18th century, and Nikolai Buchumov, a 20thcentury Realist artist, who lost an eye in a fierce debate with an Avant-Garde adversary. This device in which a group of artists create a fictional alter ego, is a ploy more commonly used in literature, for example, the poet and playwright Kozma Prutkov created by the trio of flesh-and-blood 19th century Russian writers) or in pop-music Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band of the Beatles’ fame, but you do not see it often in the visual arts. Another lively example of Komar and Melamid’s imaginative histrionics is in the ‘Rong Portraits’ series where everything seems off: from the spelling of the word ‘wrong’ to the paintings of the great minds of Western thought bearing no resemblance to, say, Socrates or Karl Marx. These are painted not in oil on canvas, but a dishrag, an oilcloth, and paisley shirt fabric. Perhaps it is a nod to Arte Povera, but with Komar and Melamid nothing is certain.

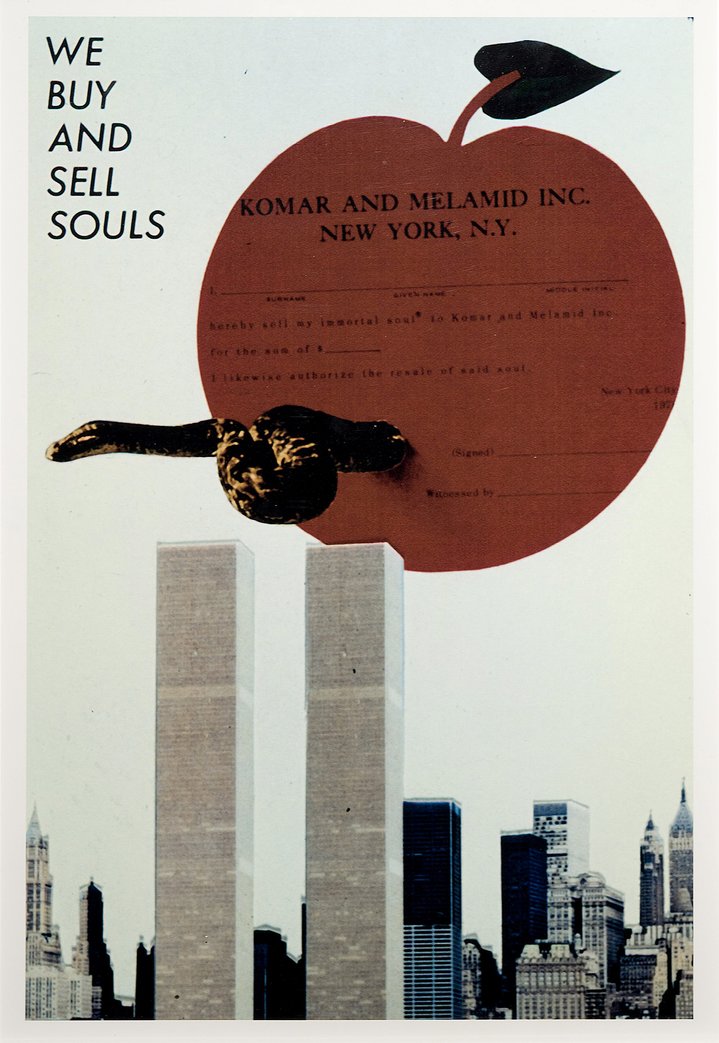

The second part of the show foregrounds the duo’s abundant American periods in emigration. These include their first US project We Buy and Sell Souls, a business venture in which they officially registered a company and launched a marketing campaign to encourage people to purchase American souls, including from renowned personalities, such as Andy Warhol and art collector Norton Dodge, in exchange for immortality. The souls acquired were later auctioned off in Moscow and New York. Whether the project was intended as a dig at the supposedly soulless and money-driven Western world (per Soviet propaganda), or a stab at playing the devil, or, short of that, channeling Chichikov, the soul-buying uber trickster of Gogol’s 19th century masterwork Dead Souls is anybody’s guess.

The multiple guises and stratagems that the artists employed to confront the ills of the New World have been summed up by the late translator of Russian literature - and Komar and Melamid’s interpreter - Jamie Gambrell, “Historians, actors, and tall-tale tellers of the might-be and might-have-been, Komar and Melamid have played the roles of prophets, propagandists, legislators, businessmen, doctors, executioners, priests, archeologists, teachers, art critics, artists—a veritable tinker-tailor-soldier-sailor chronicle of public images” (Art in America, 1982).

The same impetus that once fueled the duo’s deconstructive tactics vis-à-vis the basic tenets of communist mythology seems to underlie Komar and Melamid’s work as it came to full maturity in the West. “The exasperating expatriates,” as the artists once were called by an American critic, readily assaulted the hypocrisies and failings of untrammeled capitalism with the same verve they once exposed the glaring mendacities of the workers’ paradise. America, in the words of John Updike, ‘that vast conspiracy to make you happy’ may present more of a challenge to anyone laying bare her unsavory underbelly. After all, the mechanisms of manipulation and subjugation at work in the home of the free are infinitely more sophisticated and diffuse than those wielded in the former USSR. Not to mention that while Big Tech, the Big Five majors or Big Pharma may all indeed control our lives and be after the same thing (our dollar), yet they peddle very different products and maintain separate bank accounts. And neither may have much to do with America as it was envisioned by George Washington, another frequent subject of the duo’s paintings, more unnervingly, though one hopes, not entirely presciently featured in one of the works from K&M late period as a dollar bill-coloured facemask which partially conceals Lenin who is peeking out from behind it. A warning sign perhaps?

Whether Komar and Melamid take on America’s fascination with opinion polls of every stripe, bringing to light along the way the culture industry’s products’ pervasive mediocrity as necessary evil of any democracy (America's Most Wanted Painting / America's Most Unwanted Painting created based on public opinion); or when the artists strive to shake the seemingly indelible legacy of Stalin who dominated their childhood and continually reappears in the duo’s allegories (Stalin and the Muses, Stalin with Hitler’s Remains), they take on grave matters unflinchingly and they do it with a light, often a frivolous touch.

Looking at the works presented at the Zimmerli, I was reminded of a piece of wisdom Komar once gave me. Echoing the Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky, then a young man of 23, Vitaly believed that an artist should always keep his or her sight on the grandeur of conception. There is certainly no dearth of grandeur both in Komar’s works created with Melamid, and his own, independent work on display from the ‘New Symbolism’ series which allegorically treats the current war in Europe in ‘The Bear and the Little Bird’, or the tragic events of 9/11 in a painting called ‘Twins’.

At the exhibition opening Melamid quoted Thomas Carlyle’s well-known dictum: “All revolutions are conceived by idealists, implemented by fanatics, and its fruits are stolen by scoundrels”. Applying the statement to Komar and Melamid’s legacy (nothing short of revolutionary) the artist added: “A good example of the former could be seen tonight in the first section of the exhibition (yes, we were young idealists back then), the next one is presented in section two (the work of mature fanatics), and I just can’t help wondering where the last part leaves us all…”

During the after-show dinner, as I found myself enthusing to Komar about the retrospective, and how rewarding it must be to receive an avalanche of appreciation of the duo’s heroic achievements and how nothing - not the years of personal friendship that I truly cherished, a friendship maintained by a decade’s worth of weekly coffee that I loved having on the corner of Broadway and Bleecker with my clever and infinitely erudite artist neighbour and friend, not to mention the pilgrimages to his studio and frequent mutual social visits, or his inaugural artist talk in my Soho lit and art salon - I repeat, nothing prepared me for this spectacular display of poly-stylistic, painterly, precise body of work rich with ideas, that keeps on growing.

To that, the 79-year-old maestro responded quietly: “But we never actually thought of our work in those terms. All we did, day in and day out, year in and year out, was get up in the morning, go to the studio and do our thing”.

Komar and Melamid: A Lesson in History

Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

11 February – 16 July, 2023