Grankov and The Sound of Silence

Mitry Grankov. Forms of Sound. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Photo by Tanya Sushenkova. Courtesy of Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

‘Forms of Sound’ presents the work of Mitry Grankov at Moscow’s Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries, exploring the intersection of visual art and sound art through installations that invite audiences to activate potential sound within sculptural objects.

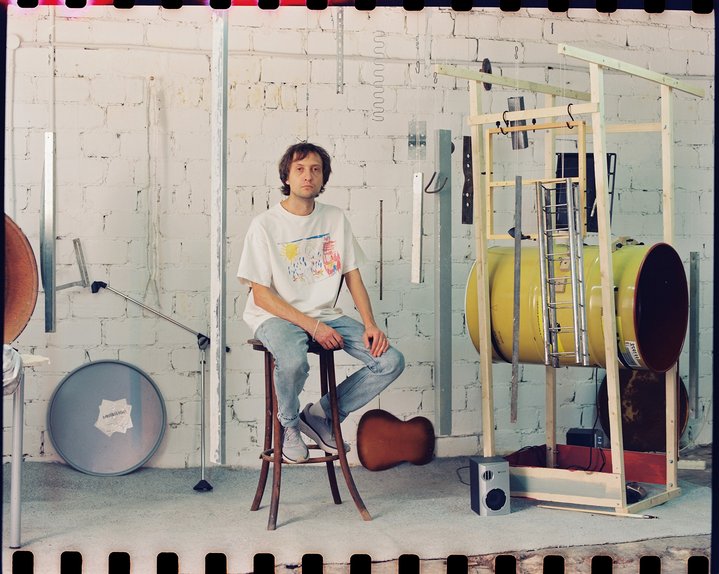

‘Forms of Sound’, at the Fabrika Art Centre, marks Mitry Grankov’s (b. 1987) first solo exhibition in Moscow. Working at the intersection of visual and sound art, Grankov has emerged as one of the most promising figures in this field. The exhibition is the outcome of a year-long programme for mid-career artists at the Fabrika Workshops. As with Grankov’s previous projects, ‘Forms of Sound’ operates on two levels: it is both a series of compelling live concerts featuring musicians from diverse backgrounds and a self-contained exhibition charged with latent sound, which viewers are invited to activate. Concurrently, Grankov is participating in the group exhibition ‘Is It All for Show?’, organised by a real estate developer in a newly renovated nineteenth-century merchant’s house.

Trained as a historian, Grankov has nevertheless been immersed in music since childhood, studying the violin and performing with classical ensembles. Alongside this, he collaborated with the independent ITS Krug Theatre and with experimental improvisational groups whose performances could be so radical as to provoke even orthodox metal audiences. “At one show with the ‘Post-materialists’, we enraged the audience so completely with our noise that we were escorted out through the back door,” Grankov recalls.

Grankov aspired to become an artist from an early age. “Back then, I still thought that an artist was simply someone who draws,” he recalls. “Later, I developed the idea of combining music with contemporary art. I imagined it as musical performance infused with elements of performance art.” The concept of creating sound objects emerged during the pandemic, when Grankov was spending lockdown in the countryside while studying online at the Free Workshops, the contemporary art school of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. It was there that he produced his first “barrels”: empty canisters stretched with strings and, in some cases, fitted with fingerboards. For these initial works, Grankov was awarded the Kuryokhin Award in 2021, one of Russia’s most prestigious prizes for contemporary art and music.

The “barrels” are sound objects, witty in their paradoxical nature. Imposing, resonant, and yet empty, the industrially coloured tins are, of course, laden with sonic potential. One feels an almost irresistible urge to strike them – a gesture that generations of musicians engaged in the so-called “art of noise” have already embraced. This lineage can be traced back to its founder, the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo (1885–1947), who championed the rebellious energy of industrial-era noise over the refined timbres of classical music, which he saw as belonging to a pre-industrial world untouched by the roar of modern machinery.

Grankov acknowledges the continued influence of the early twentieth-century avant-gardes on his practice. “There probably aren’t any particular sounds I can’t tolerate,” he says. “But I least like the sounds of the city. Noise attracts me, too, but I think I’m more focused on sound. I work a lot with strings, and strings are more about sound.”

Mitry Grankov’s sound practice emerged from the silence of the pandemic lockdown. By now, the noises of the industrial era, heard from within our post-industrial present, have themselves begun to resemble distant echoes. Grankov works not only with sound but with reverberation, demonstrating a particular sensitivity to emptied spaces and their latent acoustics.

This approach was evident in his project for the 2024 Bolotnaya Biennale, a non-commercial, non-institutional exhibition initiated by artists and curators Vasilisa Lebedeva (b. 1984) and Olga Tumanova (b. 1978), staged across unexpected sites, most often abandoned buildings. That year, the Biennale occupied a vast, derelict structure formerly housing a scientific geological prospecting institute for precious metals on Varshavskoye Highway in Moscow. Grankov transformed an entire room of this building into a musical instrument by stretching strings across the space.

Titled ‘Cabinet of Disappearing Sound’, the installation was open to the public, inviting visitors to perform a kind of spiritual séance – summoning, through sound, the lingering presence of the abandoned institute itself.

For Grankov, Fabrika functions above all as a space for art, although the allure of the former paper factory’s industrial architecture has not left him indifferent. “The spaces at Fabrika certainly attune you to a particular atmosphere,” he notes. “I remembered videos of Einstürzende Neubauten performing in a factory. And then there’s that tall stone chimney rising right next to my studio – it would be incredible to get inside it and perhaps play something there, sending sound upwards.”

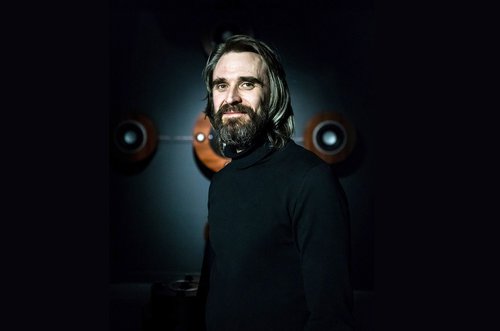

Members of Einstürzende Neubauten, incidentally, have indeed performed at Fabrika. In 2008, Alexander Hacke (b. 1965) appeared there with his solo project, and in 2019, as part of the exhibition ‘Brilliant Dilettantes’ – dedicated to the emergence of the German alternative music scene of the 1980s – one of the group’s founders, Gudrun Gut (b. 1957), gave a concert.

In ‘Forms of Sound’, Grankov incorporated a fragment of a metal stage stand found on site at Fabrika – an object that, according to the artist, produces excellent sound. Yet today’s Fabrika, which is soon to cease to exist following the city authorities’ decision to clear the site for residential development, resonates less with industrial noise than with the accumulated echoes of two decades of intense cultural life.

Several elements of ‘Forms of Sound’ migrated to Fabrika from Mitry Grankov’s earlier projects. In 2025, he took part in the art programme at Belye Allei (White Alleys) Park Hotel, located in the Moscow region. (The programme is curated by Natalia Konyukova). There, Grankov constructed instruments from scrap metal found on site – vast, rusted metal sheets bent into forms reminiscent of excavator buckets and strung with taut wires.

“While working on the large installation at ‘White Alleys’, I began to imagine a narrative,” the artist explains. “As if I were living in a post-apocalyptic world, assembling music anew from whatever I could gather from the ground.”

In this post-apocalyptic world, the noise and roar of civilisation appear to have long subsided, allowing music itself to be reinvented. In his projects, Grankov begins with music rather than with the object – an approach that distinguishes him from German 'Bikapo' Vinogradov (1957–2022), the pioneering sound artist with whom any Russian practitioner in this field is almost inevitably compared (Grankov, notably, never experienced Vinogradov’s performances live).

Trained as an architect, Vinogradov awakened in anonymous fragments of iron salvaged from rubbish dumps a mysterious power of noise that seemed to predate not only the civilisation for which these objects were once produced, but humanity itself: a primordial “music of the spheres,” the hum of the universe, older than any sound ever consciously made by humans. Grankov, by contrast, seeks to adapt any found object to the needs of music – music that should not be divided into classical and contemporary – discovering, for example, the soul of a cello within an industrial canister.

His work is neither noise nor even ambient sound. Rather than filling space, it purifies it, delineating zones of silence – the quiet necessary for sound to emerge – working with acoustic negative space. These are delicate, fragile, and ephemeral sounds, each seeming like an accidental and rare miracle that demands full attention, so slight is the chance that the same sound might ever be heard again.

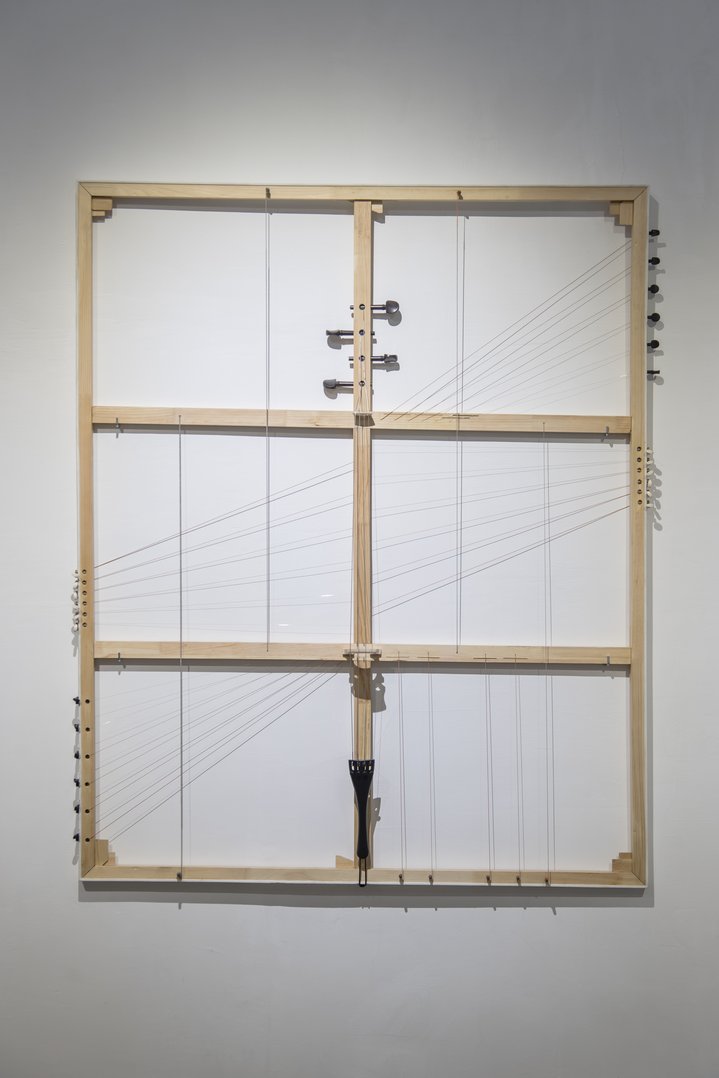

One of Grankov’s object series, ‘Alla musica’, consists of recognisable components of classical instruments – strings, fingerboards, tuning pegs – reassembled into structures resembling empty picture frames. The works readily invite comparison with John Cage’s 4'33" (1952), itself inspired by Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘White Paintings’ (1951) – white monochromes in which Cage famously perceived “airports for the lights, shadows and particles,” just as his own composition created a temporal frame in which any involuntary sound could acquire the status of music.

“Objects can sound, but are not obliged to,” Grankov writes in his explication for ‘Alla musica’. Yet unlike Rauschenberg’s ‘White Paintings’ or Cage’s 4'33", there is no nihilistic gesture of refusal here – no denial of sound or image. These frames do not point toward final emptiness or a primordial void. Instead, they contain potential music, present and latent, capable of being activated at any moment, almost involuntarily. If this is a post-apocalyptic world, it is one that remains inhabited.

As a historian and connoisseur of classical music, Grankov is interested not only in the ghostly echoes of past epochs accidentally overheard in ruins. “I’m interested in the sonic space of future epochs,” he admits. “What will be there – that’s what fascinates me.”

Mitry Grankov. Forms of Sound

Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

Moscow, Russia

11 December 2025 – 18 January 2026

Is It All For Show?

Moscow, Russia

20 November 2025 – 26 April 2026