Sasha Skochilenko and the Unbearable High Price of Freedom

Sasha Skochilenko. The Price of Freedom. Exhibition view at Koppel Project, 2023

The young Russian artist’s prison drawings are now on display in a police station in London. The Koppel Project hopes to help Skochilenko’s cause, but a major question still remains: will the artist who has already spent one year in a pre-trial detention centre in St. Petersburg be released?

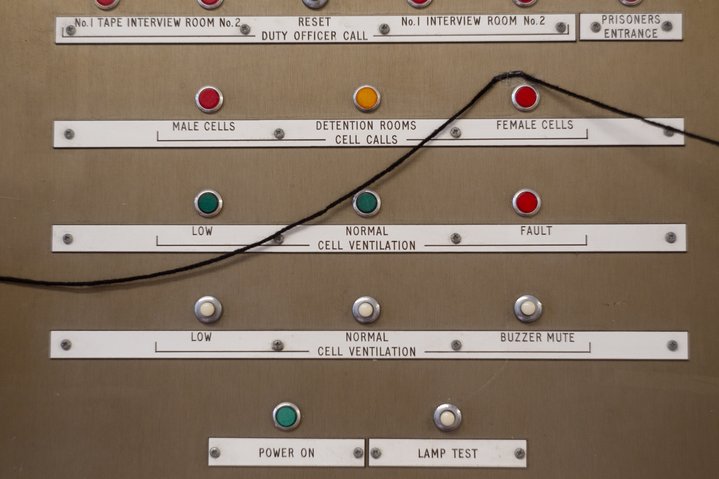

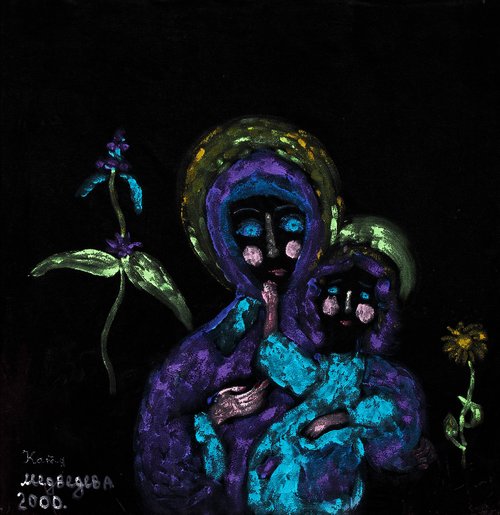

Artworks by jailed Russian artist, activist and musician Sasha Skochilenko (b. 1990) have gone on show in Hampstead, an affluent suburb of London, in a former police station recently repurposed as an experimental art gallery and creative hub. It is an initiative of the Koppel Project which aims to “develop curatorial projects and thoughtful exhibitions that provoke dialogue and generate diversity in the art world … to stimulate transformative cultural exchange.” The exhibition curators, Anna S., Dmitrii Moskovskii and Varvara found a quasi authentic setting for Sasha’s prison drawings in station’s prison cells with their metal doors.

The 32-year-old is being held in a detention facility awaiting trial on charges of “spreading false information about the Russian army.” In March 2022, the artist substituted price tags in a local supermarket for notes detailing the airstrike on a Mariupol theatre, described as “fake news” by the Russian authorities. Reported by a pensioner, Sasha was detained in April 2022 and charged under a new law banning “the dissemination of knowingly false information.” If found guilty, Skochilenko, who will be held in a pre-trial detention centre until July 2023, faces a fine of three million roubles (approximately $45,000) and up to ten years in prison. The artist argues that the charges against her are disproportionate and excessive. Although Skochilenko’s defence provided personal guarantees as well as legal documents for the apartment where Sasha could stay under the house arrest, as her mother and sister live in France, and she has friends in Ukraine, the court decided she might try to flee so house arrest was denied. Sasha has now been named a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International. Meanwhile, her legal representative Yury Novolodsky, faces two disciplinary cases on unspecified charges that may cost him his license. The hearing into Novolodsky’s case is scheduled for 20th of April, the same day as Sasha Skochikeno’s trial.

Skochilenko suffers from celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder where eating gluten causes damage to the small intestine. She cannot maintain a strict diet while in detention, and malnutrition may cause complications, in rare cases even cancer. As Skochilenko’s girlfriend Sonya Subbotina reported, the artist experienced severe pains in the lower part of her abdomen for a long time, only recently diagnosed as an ovarian cyst. Dmitrii Moskovskii, co-curator of the exhibition, told Art Focus Now, the only positive effect that the publicity of Skochilenko’s case has achieved, is an easing in some of the strict prison rules and regulations.

Skochilenko is not afforded any timely medical or psychological help. Bullied and harassed by other inmates, the artist began to experience severe mental health issues. This together with unsanitary prison conditions, has further contributed to her ill health and aggravated an existing bipolar affective disorder which makes her particularly vulnerable to stressful and traumatic events.

In 2014, struggles with her mental condition led to her publishing an educational comic book which later became known as Notes on Depression. Skochilenko was among the first in a new generation in Russia to talk openly about her experiences in a candid, compassionate and humorous way. The book was well received by critics and much praised by those who suffer from depressive episodes. Later, the artist made comic books about the symptoms of bipolar affective disorder, anxiety, and other mental conditions. In addition, she illustrated Bipolar Disorder, a book by Masha Pushkina. Skochilenko’s graphic works were also featured by such non-profit charitable organisations as Partnership of the Equalsand Bipolar Explorers Association.

“If just a couple of months ago I had been asked what is worse, jail or depression, I’d have said without hesitation that of course depression is worse. But sometime in early September I started having second thoughts about this. Now I think that the worst thing is having depression while you are in jail,” wrote the artist in one of her letters from prison, dated 6thof December 2022. Further detention poses a serious threat not only to the artist’s physical and mental health, but to her life in general.

The Koppel Project exhibition has been organised with financial backing from the Russian Democratic Society, a non-profit organisation in the UK. It narrates Skochilenko’s story and aims to provide an insight into her current situation. According to Dmitrii Moskovskii, all of the artist’s drawings and artworks are currently under arrest, which means the originals cannot be taken out of the prison. The curators had to carefully scan her drawings and produce high-quality prints of the same size. Each of the three curators comes from a different discipline: Anna S. is an artist and photographer, Moskovskii is studying to become a fashion designer and Varvara is a visual artist who also carried out the research for the exhibition, translating documents, official protocols and correspondence. For the exhibition space Anna S. made a piece of woven textile listing all of the accusations against Sasha, the words written in embroidery, and visitors are invited to deconstruct it by pulling it apart, literally “unweaving the story” and “unspinning the yarn.” Moskovskii also contributed some textiles on display. Varvara originally initiated the dialogue with Sasha Skochilenko by emailing her in prison and then asking permission to do a show.

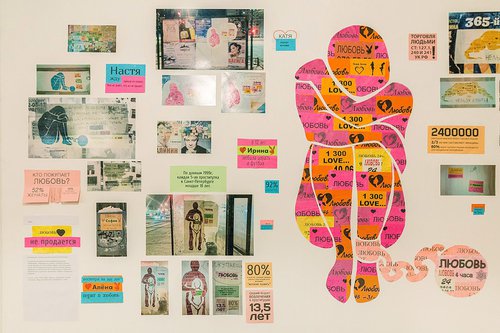

In the exhibition there is the ‘Context room’, conceived by Varvara, where you can follow the development of Sasha’s case, read her statements and letters, all in the presence of a policeman painted on the wall by Varvara. As you read the texts the artist’s music is played overhead – she started out as a musician although it is her graphic works for which she is known. Although you move from one small cell to the next, the project is not about incarceration but freedom - internal freedom. Her work gives you some insights into the world of Russian prisons, especially from the perspective of a woman. Apart from a few memoirs, letters and sketches, there is no in-depth study on how women perceive their experiences in Russian prisons.

Although the situation is desperate and the chances of Sasha’s release seem slim, the curators attempt to offer an antidote to the feelings of helplessness and despair: they suggest that viewers leave notes on small pieces of paper, specifying how they would like to help Sasha. Apart from a certain therapeutic effect, this also helps to switch people’s focus from what they cannot do, to something that can be done, even in small steps.

The last words must be from the artist herself, taken from one of her prison letters: “But behind my back, the colossal civil society has risen. If only YOU could see how polite the high-profile officials are with me now. I scare them like a flame, and no one has laid a finger on me here—and it’s not because of me, but because of YOU all: independent media, journalists, civil activists, performers, human rights activists, free hippies, musicians and artists, and also just peace-loving men and women with a conscience and empathy.”

Quotes from Sasha Skochilenko’s prison letters were taken from the website www.skochilenko.ru/en launched by her supporters.