Maxim Didenko’s Production ‘Cremulator’ Premieres in Berlin

Cremulator. Directed by Maxim Didenko. Based on the novel by Sasha Filipenko. Photo by Victoria Nazarova. Courtesy of Cremulator team

This first production of Sasha Filipenko’s novel of the same name is based on real events and tells the nightmarish story of the head of Moscow’s first crematorium.

It is 23rd of June 1941, one day after the USSR was attacked by Nazi Germany. However, in ‘Cremulator’ the action unfolds around another totalitarian state: Soviet Russia under Josef Stalin, and this is the date on which crematorium boss Pyotr Nesterenko was arrested. He was the head of Russia’s first crematorium, in Moscow, located close to one of the city’s largest cemeteries. During the day, it was used as a normal crematorium for local citizens who had passed away, even famous people like the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky were cremated there. However, at night it was used to incinerate the bodies of those executed by Stalin’s NKVD. Under the cover of darkness, it was a (supposedly secret) incarceration and quick erasure from any memories on earth.

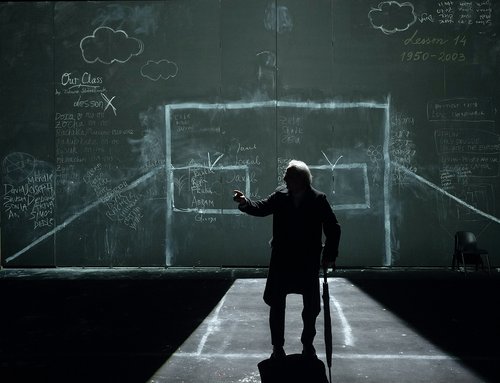

The play’s protagonist Nesterenko was a real person, and the play is based on historical evidence and the interrogation notes made after his arrest by the NKVD before he was executed in 1942, just one more among the many bodies he hadbeen secretly turning to ashes at night. A cremulator is a mechanical device that grinds human bones into dust after all the soft tissues have been cremated. This is the name of a novel by Belorussian-born writer Sasha Filippenko, in which he creates a narrative out of both the legal protocols of Nesterenko’s interrogations and his own imaginary diaries where he tells his story to his first love, Vera. Filippenko’s book was adapted for the theatre by German playwright Johannes Kirsten and has been staged for the first time by renowned Omsk-born director Maxim Didenko who left Russia in 2022. The play was first shown from 2nd to the 4th of February 2024 in Berlin and will travel on to Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Limassol, Cyprus this Spring.

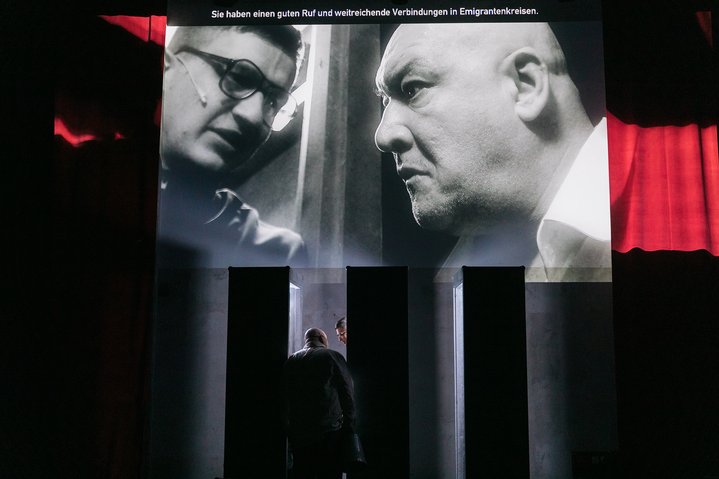

There are four characters in the play: Nesterov is played by Maxim Sukhanov (critics hail Sukhanov as an actor who could play a phone book and be amazingly brilliant), the NKVD investigator is played by Igor Titov; then there is the part of Nesterenko’s lover Vera to whom his monologues are addressed, played by Yan Ge or Svetlana Mamresheva on different days; and finally a nameless, silent man dressed in black who holds a video camera. The latter brings an entirely new dimension to the play, through the eye of the camera he is a kind of witness with a constant live broadcast on a screen above the stage. Even the most intimate moments, a humiliated Nesterenko curled up in his coffin resembling cell, or when he confesses his feelings to his imaginary fiancée only to get rejected, are ruthlessly exposed on the screen which appears to tell a true story unlike the lies of the real people acting on the stage below.

Pyotr Nesterenko was born before the Revolution in imperial Russia where he served as an officer in the imperial army. After the coup he left Russia for Kharkiv with the White Guards, then lived in exile in Istanbul and Paris. From Paris, he was later lured back to the Soviet Union to head up the country’s first crematorium, which he did until his arrest in 1941. Crematoria became popular in the late 1920s in Russia when the new Soviet regime had begun to fight old traditions and rituals, especially those connected with religion, and they promoted new traditions, like a fiery funeral without a mass and a grave.

Nesterenko was enthusiastic about it and even proposed to build an airport next to his crematorium in Moscow, so that the ashes of Soviet citizens could get dispersed into the air without any delays. He even sold tickets to official incarcerations and the demand was strong. He says in the play: “There is a technological orifice one can watch. The lucky ones can see how the brain burns. The luckiest, how the head gets separated from the body. But later there is nothing more to see, there is only cinders left”. Yet, in the end Nesterenko’s own enthusiasm and steadfast loyalty did not save him from detention and death. Because he had lived in exile abroad, he was still labeled a probable spy and when the time came, arrested and shot and himself turned into ashes, and that was a true story.

Although the plot does not vere from the real events, what the audiences see on stage in Berlin’s Säälchen goes above and beyond time and place, staying true to the documentary form, Didenko has turned his Cremulator into a fable for the current times. The play has been staged in Berlin in Russian with German subtitles, but most of the audiences consist of Russian speakers, many of whom fled Russia to settle in Germany because of the war in Ukraine and the subsequent clamping down on freedom of expression in Russia. The play is filled with memes applicable to the war and to ongoing abuse of human rights in today’s Russia.

Nesterenko recalls how as an officer he had at first felt excitement about going to war and he dreamt of coming home as a hero. Later, he found nothing heroic in the battlefield but hoped that he would at least experience some noble humane feelings while burying his comrades-in-arms. That did not happen either. “I have ceased to cry for my dead comrades. I have started to laugh” says a hysterical Nesterenko after realising that he admits, “there will not be four months, that’s an infinity”. Russian troops had expected to secure victory in WWI within just four months, a gross underestimation and the stuff of propaganda. At one point, Nesterenko tells the investigator how hard it was to be a Russian immigrant in 1920’s Europe, discriminated for having a Russian passport. All of a sudden, the camera is directed at the spectators, most of them Russian. Titov who plays the investigator asks everyone if they are planning to return to their homeland and what they think of its current state.

Cremulator is immediate, powerful and thought-provoking, the direction and acting amplified by Sergey Nevsky’s musical score and the set design by Alexander Barmenkov, who has created a sinister world out of a few small structures imitating concrete which transform from beds into coffins and from prison cells into flowerbeds. Ultimately, inspite of some historical parallels which the play explores, Cremulator has a universal theme, about the vulnerability of memory. A cremulator turns bones into dust to decompose the last remnants of what was once human. Repression does not only eliminate what is deemed as unwanted, but it goes further: it aims to eradicate our memories.

Cremulator

Schouwburg Amstelveen

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7 Mai, 2024

Atze Musiktheater

Berlin, Germany

5–6 June, 2024