Who Killed Jakub Katz?

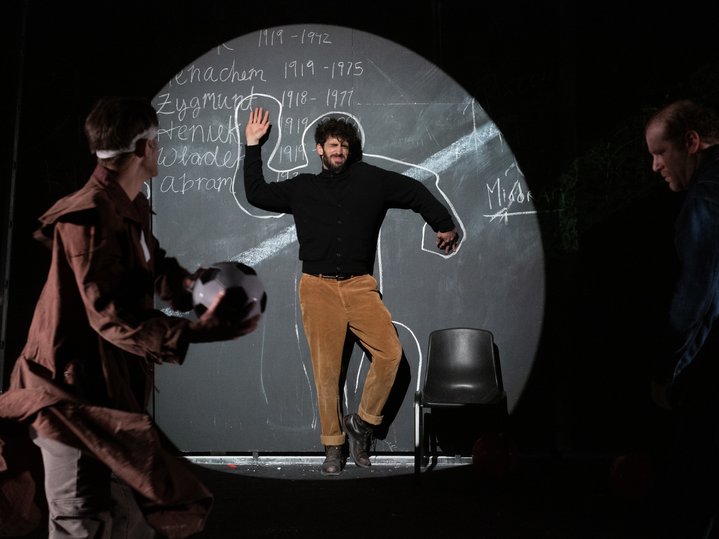

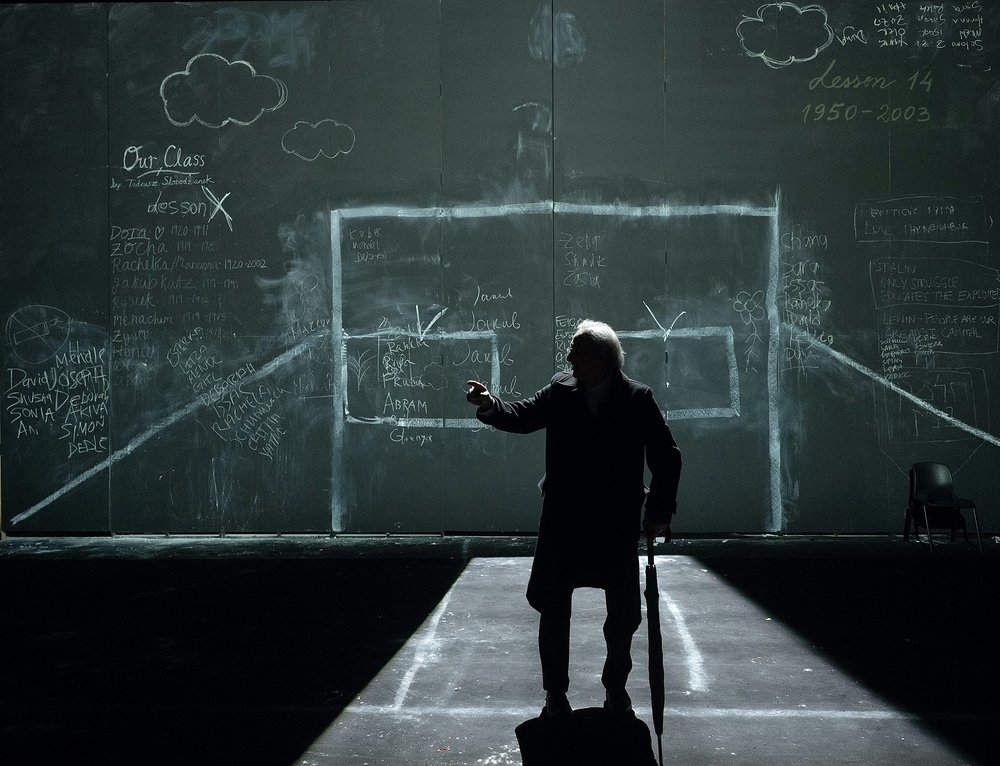

Richard Topol. Our Class. Play by Tadeusz Słobodzianek. Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Fisher Fishman Space. Photo by Pavel Antonov.

Ukrainian born director Igor Golyak and Russian theatre producer Sofia Kapkova have come together to stage a timely premiere of ‘Our Class’ in New York. This haunting, powerful and controversial play by Polish playwright Tadeusz Słobodzianek is based on unspeakable yet real events that happened in the town of Jedwabne during World War II.

In 2000, the slim book ‘Neighbours’ by historian Jan Tomasz Gross was published in Poland, a historical account of the Jedwabne massacre. The horrors unfolded one fateful date in the Summer of 1941 in Jedwabne, a Polish village where the Catholics inhabitants turned on their Jewish neighbours, slaughtering them in an act of collective unspeakable barbarity. Kate Korycki, a researcher of contemporary Polish memory politics, describes Gross’s research and the writing of the ‘Neighbours’ as a “journey to seeing, or rather of the puncturing of his unseeing” of Polish involvement in the Holocaust. What happened there was unthinkable, as Gross admits in her book ‘Weaponizing the Past. Collective Memory and Jews, Poles and Communists in Twenty-First Century Poland’, “I decided to write, using Jedwabne as an example, of how Polish neighbours tortured Jews. I did not realize yet that, at the conclusion of the series of murders and cruelties committed that day, all remaining Jews were burned … It took me four years to understand”.

When it was published, the book deeply divided Polish society, with those who openly acknowledged and publicly apologized for these crimes and those who were in denial - some even lobbying for and introducing the infamous 2006 ‘Lex Gross’, an amendment to the Criminal Code regarding crimes of the defamation of the Polish nation. Today there is an aching abyss between these polarized positions, to take Korycki’s words, of seeing and unseeing. Opening your eyes feels only like a first step in what needs to be a tough journey of acceptance.

Some years after the book was published, in 2008, celebrated Polish playwright Tadeusz Słobodzianek wrote a play called ‘Our Class’, based on the Jedwabne massacre and it is being staged currently in New York by an international troope including both Russian and Ukrainian emigres. The director is Igor Golyak, born in Ukraine, was trained in Moscow’s Russian Theatre Art Institute (GITIS) where his mentor was well-known director Sergei Zhenovach. In 2009 he emigrated to America and founded the Arlekin Players Theatre that year. For this performance of Our Class he has joined forces with Sofia Kapkova, a Chita-born producer from Moscow and her MART Foundation, most of whose team moved from Russia to New York and Tel-Aviv after the start of Russian-Ukrainian armed conflict in 2022. Another unexpected Russian connection in this project is that Slobodzhianek himself was born in Yeniseysk in Siberia in 1955.

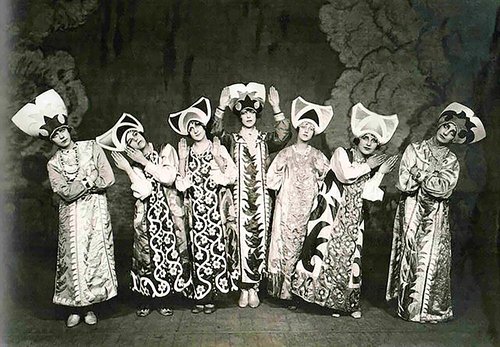

‘Our Class’ is the saga of the lives and deaths of ten Polish classmates — five Catholic Poles and five Jews — which focusses not only on the massacre itself but what came before and for decades after, its legacy. Time is condensed in the play, the classmates grow and mature in Poland of the 20s and 30s. Tensions whether personal, religious or political grow between what were once innocent first-graders, just as they did in Polish society. This peaked in the early war years between 1939 and 1941, during the brief period of the Soviet occupation and just prior to Nazi Germany taking over Poland. In the summer of 1941, there was a brief intermission after the Soviets had left and before the Nazis came when the tensions which had been simmering, were released in one of the cruelest and bloodiest massacres imaginable. Young Poles Rysiek (played by José Espinosa), Władek (played by Ilia Volok), and Heniek (played by Will Manning) killed their school friend Jakub Katz (played by Stephen Ochsner) to avenge the harm done to themselves and their families by pro-Soviet Katz. This murder sparked off that fateful day, 10th of July 1941. This day does not end in the first act or even at the end of the play, it encompasses the rest of their lives.

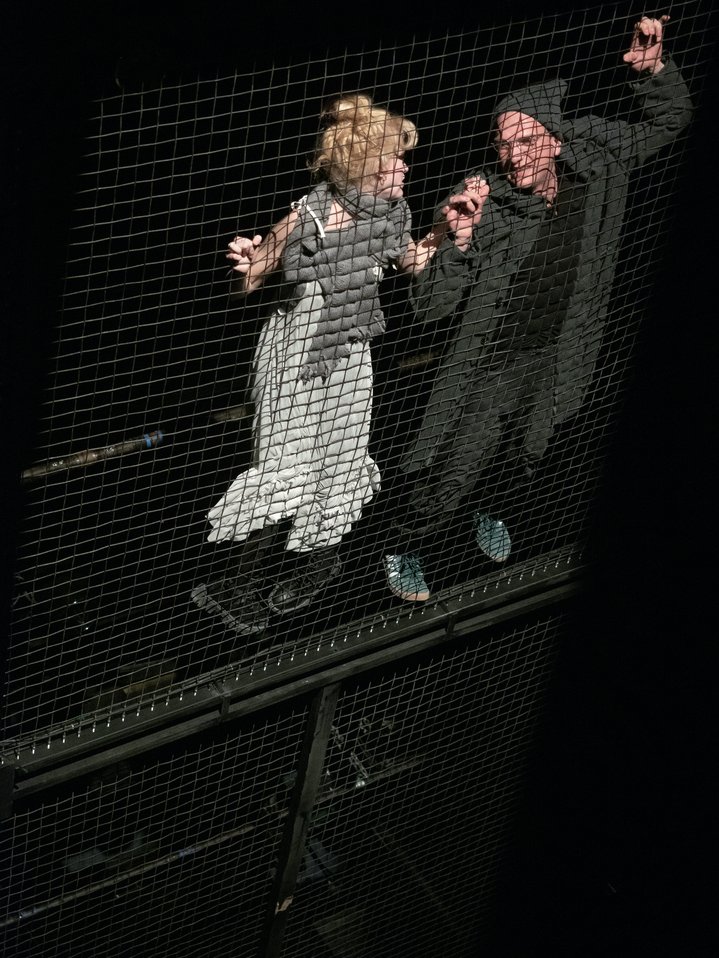

It so happens that some days and even minutes in our lives are more important than all the others. In those moments time is compressed and acquires a new dimension - historical, even biblical - when everything becomes symbolic and actions take on a profound meaning. As if God is manifest in history but not necessarily in human affairs. This is what the creators of Our Class capture in their enactment of the seemlingly endless day of the Jedwabne massacre. A large, wooden cross is aptly carried around on the stage by the Catholic classmates. It not only stands for sacrifice and redemption from sin, but also for the punishment of Jesus by Romans and his suffering. The ladder carried by the Jewish classmates represents Judaism. While the biblical patriarch Jacob dreams of a ladder to heaven with angels ascending and descending, Jakub Katz sits at the top of his ladder in a nightmare surrounded by black wolves, who are ready to attack. In both cases the ladder recalls a prophecy: future greatness for Jacob and the impending murder of Katz. These religious symbols coexist on the stage, emphasizing the inability of humans - even children who are classmates - to coexist. This is not a trait, but a choice. Katz, wounded and half-alive, chooses not to hide to save his life but, like the biblical Isaac bound on the altar on Mount Moriah by his father Abraham, was willingly waiting to be sacrificed, or spared by Divine intervention. Perhaps, Jakub Katz was waiting for his classmates to make their choice, either to spare his life or to finish him off. God did not intervene and the Holocaust happened. Katz’s school friends chose to kill him.

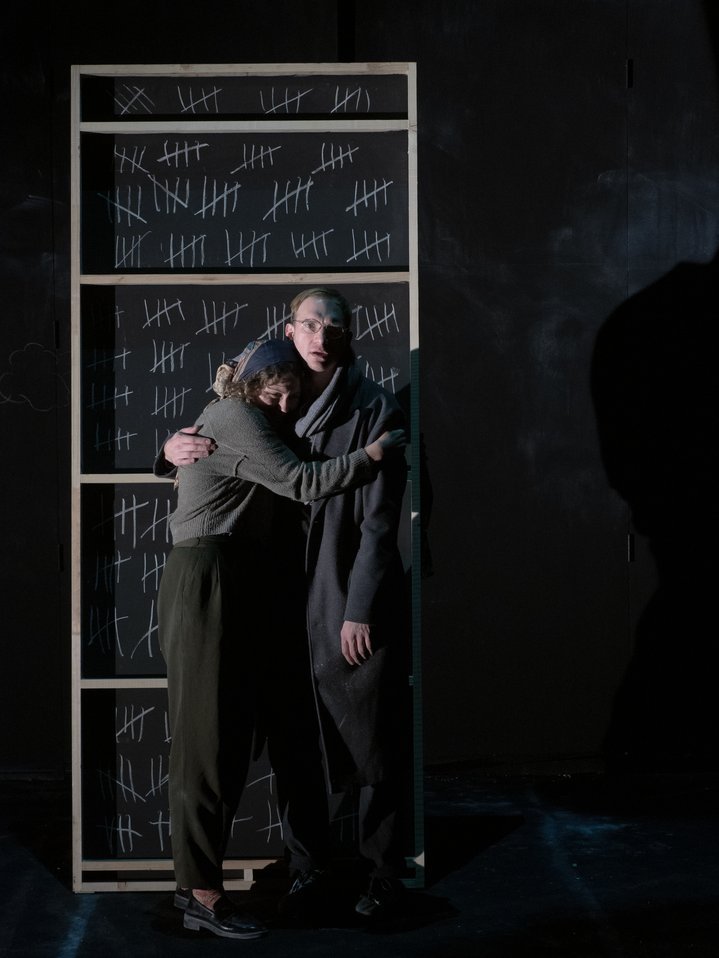

The production team of ‘Our Class’ have created an immersive visual environment, which artfully emphasizes the meaning and symbolism behind the spectacle. There is a huge blackboard at the back of the stage. Chalk texts and drawings made by the cast throughout the play have manifold meanings, from the black and white perspective of schoolchildren, to the polarized positions of grownups, to the writing, erasing, and rewriting history. However, in the most dramatic scenes, the actors are in silhouette and there are enlarged pixelated images which serves to overshadow this stark black and whiteness with many shades of grey, bringing the performance added nuance and depth.

A thick, white chalk line drawn by Jakub Katz just before the opening of the show marks the border of the stage. In Slavic folklore, a chalk line (or square, or circle) is used for protection against ghosts and evil spirits, who are unable to cross it. It also prevents ghosts from seeing those who are behind it. So from the second act of the play onwards, the ghost of the murdered Jakub Katz, cannot be on the stage but he is present in all the scenes, wandering around, dancing, playing music all the time at the margins. Katz and the question of who killed him are never revealed yet they do not disappear. Paradoxically they remain at all times the central focus of the play.

In the end, those who killed Jakub Katz eventually die. Yet his ghost still haunts Poland today: many people see it, many others continue to ‘unsee’ it. Although the creators of ‘Our Class’ divide the stage action into chronological ‘lessons’, the play does not teach us the lesson of history. In fact, they take pains to show how this story is not yet history. It even reaches across the ocean, lingering in retirement homes and in families. The question of who killed Jakub Katz is left open, it is always relevant and forever burning.

Our Class

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Fisher Fishman Space

New York City, NY, USA

January 12 – February 11, 2024