Creating the feminine

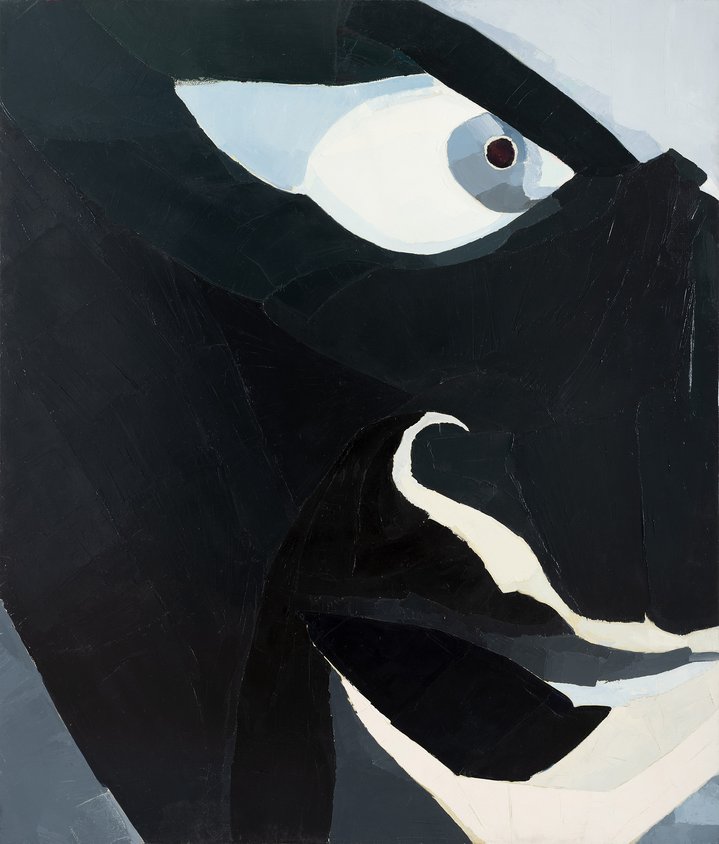

Natalia Turnova. Sniper. 1994. Courtesy of Alina Pinsky Gallery

A large group exhibition of nearly a dozen female artists has opened in Moscow’s Alina Pinsky Gallery. It brings together works from several generations of women in the arts in Russia, from the modernist pioneer Natalia Goncharova to young millennials.

Art can be relevant more than once. ‘Sniper’ (1994) by Natalia Turnova (b. 1957), one of the two largest works at the centre of the Alina Pinsky Gallery show, depicts a person with white hair looking at the audience through a rifle scope. The painting illustrates the ‘white tights’ legend during the First Chechen War (1994–96) in Russia when the tabloid press repeatedly reported that women from the Baltics were fighting on the side of the Chechens. It is the stuff of legend as so far there has been no proof.

The ‘white tights’ legend is ambivalent. On the one hand it asserts the importance of the strong woman, but on the other hand, it instills fear. And it fits into a long series of myths about a white goddess who appeared at the beginning of feminism’s first wave, including Freya from the Book of Uri-Lind (a hoax from the middle of the 19th century) as well as Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale Snow Queen. The propagandistic role of this mythological construct is clear, but less obvious is the context: the emancipation of women from Soviet gerontocracy produced a generation of politicians who both attracted and repelled at the same time: Valeria Novodvorskaya, Galina Starovoitova, Irina Khakamada.

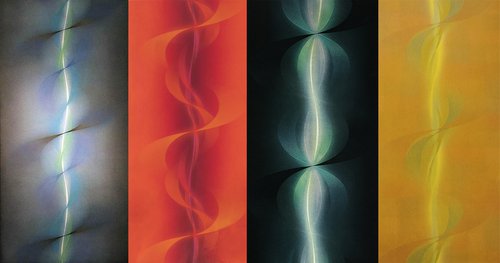

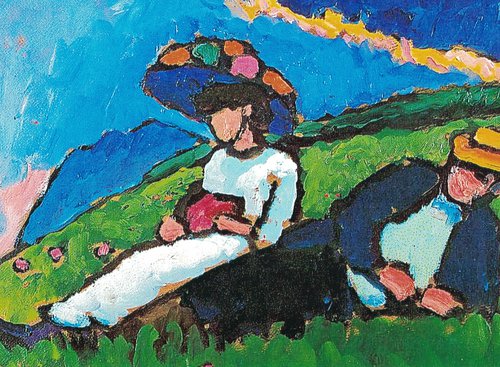

The history of new women's art in Russia begins at perestroika. Not because there were no female artists in Russia before that, but because they occupied a completely different place. In official art, they had a secondary role, and in unofficial art even less. They were muses, wives, girlfriends, lovers, or drinking buddies of the unrecognized geniuses of the underground and they almost never went beyond a social cliché. Abstract painter Olga Potapova (1892–1971)’s contemporaries had nothing to say about her paintings other than that she worked ‘in the shadow of her husband’, Evgeny Kropivnitsky (1893–1979), the leader of the Lianozovo school: her ‘Composition’ (1959) is included in this show. Lydia Masterkova (1927–2008) is one of the few exceptions, yet her independent character led her to virtual self-isolation for over 30 years and here represented by of her best abstract works, ‘Composition’ (1958). Sadly Rimma Zanevskaya-Sapgir (1930–2021) was only remembered after she died: an op-art artist in the 1960s-80s (the two ‘Compositions’ exhibited are from 1968), she became an icon painter during the last decades of her life.

The exhibition at the Alina Pinsky Gallery reflects not so much gender related as generational patterns, spanning from Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) to Svetlana Hollis (b. 1995). Without claiming to be encyclopedic, the exhibition brings together the work of several artists, each of whom created her own idiosyncratic world. Natta Konysheva (1935–2022) lived her life as an active hermit. Although she was well known, she remained apart, ironically and with a nod to surrealism portraying bohemian life using her own sketches. There is Natta herself, a petite lady with a notebook, a frequent visitor and character at Moscow parties; her ‘Presentation of Lavrin's book ‘The Haron Chronicles’ (1993) is about a typical literary event: some guests are drinking, others are eating, but in the centre there is a skeleton who is smiling, while under the ceiling small black demons carry away the souls of the party-goers. This painting redefines bohemian life as a cycle of death, quite in the spirit of the literary man who has become the protagonist of the event.

A painting by Alyona Kirtsova (b. 1954) marks the transition to a new stage in history. Her ‘Interior of a Corridor with a Mirror’ (1986) synthesizes realism and abstraction: the main motif is abstracted to a minimalist image. Kirtsova is an artist who has had many solo exhibitions. Thanks to galleries, museums and foundations, new female art gets a space in the late 1980s. Maria Serebryakova (b. 1965) was one of the most active participants of the Moscow New Wave in her youth. Natalia Turnova was one of the stars of the Regina Gallery in the nineties.

The institutional world of the nineties gave birth to a whole new system of social relations, making possible a brutal corporeality, and giving rise to fresh pictorial possibilities. For Vika Begalskaya (b. 1975), what is of central importance is that a painting evokes excitement and emotion on the canvas, which she conveys using bright colours and bold subjects: her 2005 ‘Girl with a Guitar’ is a portrait of a nude woman against a background of a factory chimney and a high-rise building, painted with rough strokes and in complimentary colours. Alexandra Paperno (b. 1978) works with layers of rice paper fixed on canvas. Combined with acrylics, rice paper works like a glaze and creates a sense of depth in the space depicted, balancing the work between dream and reality. Irina Petrakova (b. 1980) destructures classical painting: the Rubensian women and the nude from Edouard Manet's ‘Lunch on the Grass’ are included in ‘Untitled’ (2022), completed a month before the exhibition, but these figures with clearly outlined contours are doubled, flaked, and smudged by charcoal washes and powerful strokes

And how do we create our beauty?

Moscow, Russia

November 17, 2022 – January 30, 2023