Capitalism Kills Love: Serebrennikov’s Marriage of Figaro in Berlin

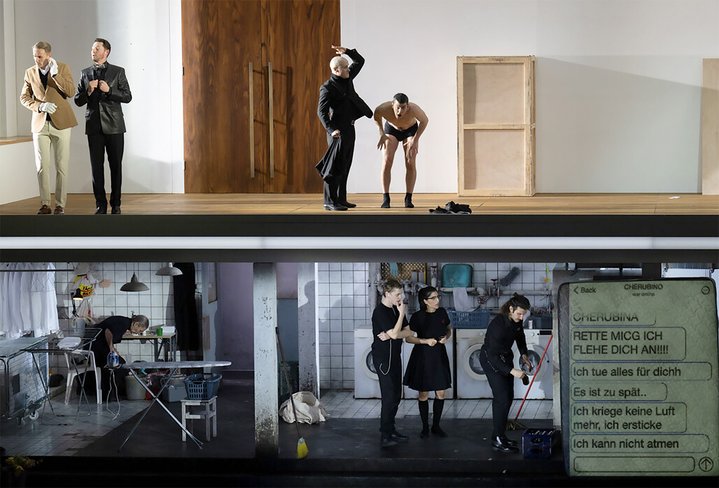

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The Marriage of Figaro. Directed by Kirill Serebrennikov. Berlin, 2024. Photo by Monika Rittershaus. Courtesy of Komische Oper Berlin and Monika Rittershaus

The most famous Russian theatre director in exile, Kirill Serebrennikov has filled Mozart’s comic opera with caustic critique that addresses today’s economically polarized society, and Count Almaviva collects flashy contemporary art.

This is the second time Kirill Serebrennikov has directed Mozart at the Komische Oper in Berlin. In Spring 2023 he produced Cosi fan tutte, and Don Giovanni is to follow next year which will complete the Mozart–Da Ponte trilogy. The director has a long history with the Komische Oper, the first one he staged was Rossini's The Barber of Seville back in 2016, with hindsight a kind of prequel for the story of Figaro and Count Almaviva.

If an opera did not require an orchestra or singers, then this production could be seen as a one-man-show even without Serebrennikov’s actual appearance on stage. He is not just the director either, Serebrennikov also designs the stage set and costumes which are here as important as the plot and music. His achievement is chiselling a sharp and scathing critique of class inequality and abuse out of this otherwise very traditional classic comedy about female chastity and marriage.

The stage is divided horizontally into two parts. The upper floor is spacious, almost empty – large echoing rooms are are privilege afforded by the very wealthy – inhabited by Count Almaviva and his wife Rosina with servants coming back and forth to serve them. The lower floor is a tile-clad backroom full of lockers, washing machines and ironing boards. Here servants sleep and eat, smoke and gossip. The actors are dressed in overalls. Susanna receives a wedding gift from her master – originally, a bed, symbolized here by a mattress which hardly fits downstairs. Her panicky texting with Figaro is projected onto it, the connection often failing.

Upstairs, the Count and Countess and their well-dressed guests find themselves in a sterile space: luxurious but unable to provide anything except superficial glamour. A great place to visit but awful to live in it. The dialogues between this aristocratic family and their visitors are dry, they have a stiff upper lip. Their connection is also failing – not the wifi but their inability to bond. Now and then you see a highly polished metal sculpture echoing Henry Moore or Tony Cragg, dragged from place to place, beloved by the socialites on the top floor. It seems that owning an expensive piece of art is nowadays as prestigious as claiming a newlywed bride’s virginity by Droit de seigneur in Figaro’s times.

Kirill Serebrennikov is no conventional opera director. The voices are exceptional – Tommaso Barea as Figaro, Hubert Zapior as Count Almaviva, Penny Sofroniadou as Susanna, Karolina Gumos as Marcellina and Nadja Mchantaf as Countess Almaviva. But Serebrennikov has introduced actors who do not sing, transforming the opera into a drama performance. Cherubino’s part is divided in two, and what was originally Mozart’s adolescent and almost androgynous Cherubino has been split into a male and a female performer. Played by Georgy Kudrenko, Cherubino’s male self is suddenly mute and Kudrenko uses such exaggerated gestures that is reminds you this is not just all serious social commentary but a comedy at heart. Having lost the ability to speak, Kudrenko uses his whole body, from his hands and feet to literally the tips of his hair, to express the extreme passions of a shy teenager unable to understand what is going on inside his body as he interacts with the world around him. His female alter ego, Cherubina, is played by Susan Zarrabi.

Nikita Kukushkin, an actor who has worked with Serebrennikov since in his Moscow years, plays the Count's aide. Throughout he does not speak a single word, but he is as quick as mercury and his body language envelopes not just him but the whole cast in a tribal dance which unites them into a single action. In the end it is these silent roles by Kukushkin and Kudrenko which produce all the stress and tension as well as the humour on stage.

The presumed rights of an aristocrat to commit acts of erotic violence, around which the plot of Figaro traditionally unfolds, is transformed by Serebrennikov into the right of the extremely wealthy to commit economic violence in which power cames from wealth. Both affect personal relationships on all social strata. On the upper floor there is a neon sign, ‘Capitalism kills love’ which looks less like a sign of resistance and more like an expensive work of art by the likes of Mario Merz or Tracey Emin.

Serebrennikov’s Cosi fan tutte, The Marriage of Figaro and the upcoming Don Giovanni are being staged by the director in exile. Serebrennikov originally worked on Cosi fan tutte for its premiere at the Zurich Opera in 2018, while he was under house arrest in Russia. After a narrow escape, where he was eventually sentenced to a fine, Serebrennikov left his home country. His Moscow theatre, the Gogol Centre has ceased to exist, his films are no longer screened, and his plays are no longer shown on stage in Russia. Serebrennikov is openly gay; recent Russian laws have labeled all LGBT+ activities as ‘extremist’. Serebrennikov has spoken out against Russia's military invasion in Ukraine, probably why his productions were suddenly banned. Russian actors and performers who are working for him in the Marriage of Figaroand other productions in Europe also now face repressions in their home country. Falling from the top floor is not only the result of capitalism – a single blow of insanity by politicians can ruin lives and make even those at the top of their game go under.

The Marriage of Figaro

Berlin, Germany

19 and 26 May, 2024, 23 November – 27 December, 2024