The Art of Research and Fake Facts

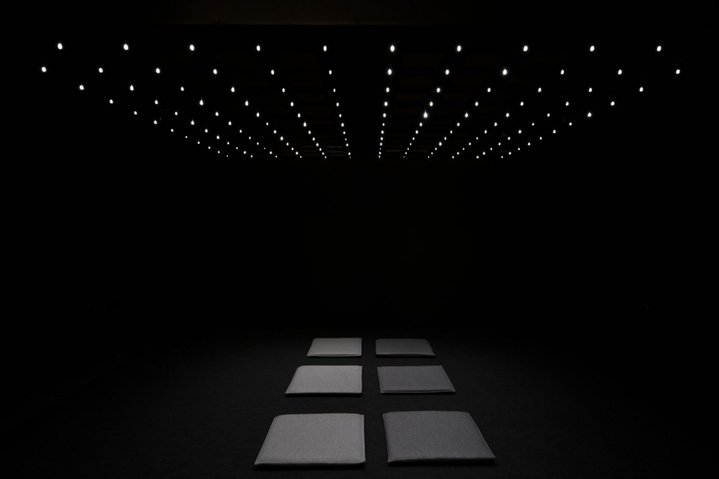

Star Vengeance. Exhibition view. GES-2. Moscow, 2023. Photo by Daniil Annenkov. Image from the GES-2 social media accounts

Artists in Russia have long held a fascination for scientists and as the exhibition ‘Star Vengence’ at GES-2 in Moscow shows, pseudo-scientists are now having their day. In this era of post-truth, who can we believe?

Currently on show at Moscow’s GES-2 House of Culture is a compact yet fascinating exhibition ‘Star Vengeance’ suggesting that human history is made up of strange coincidences which throw a spanner in the work of scientists, if not science in general. One of the main protagonists in the show is Anatoly Fomenko (b. 1945), a Russian mathematician and artist (whose works on paper are included in the show), who has been known over the past three decades for his pseudoscientific ‘New Chronology’. Put simply, he argues that the entire ancient history of mankind consists of the same events being duplicated over again, meaning that we end up talking about the same thing. Fomenko went so far as to criticise the written sources which form the basis of accepted science.

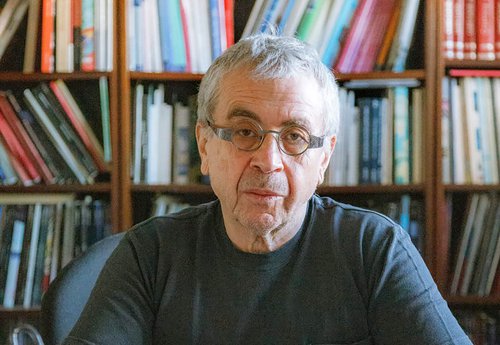

One of his predecessors, a revolutionary in his field who popularised science, Nikolai Morozov (1854–1946) similarly had a mistrust of traditional chronology and he is one of the heros of ‘Star Vengeance’. Long before Fomenko’s ‘New Chronology’ he had predicted the splitting of the atom, albeit rather speculatively. Another of the exhibition’s heros is also its co-curator artist Alek Petuk (b. 1984), who made a film ‘Petukhov:Petukhov’ inspired in part by the fact his name is coincidentally the same as an influential extreme-right science fiction writer and publisher from the 1990s, Yuri Petukhov (1951–2009). There are a lot of biographical coincidences woven into the threads from which Petuk then weaves the narrative in his film. It is not meant to be funny; it is an approach aligned with another speculative theory called coincidentology, conceived by Russian-Israeli author Yoel Regev (b. 1972) cobbling together the Kabbalah and European philosophy. According to coincidentologists, coincidence is a revolutionary force through which the world can be both explained and changed. Regev is one of the speakers in Petuk's film, while the artist himself is a member of the ‘Coincidental Institute’ created by the latter and is actively recruiting supporters, including through this exhibition.

The exhibition asserts that scientists today exist in a frontier between science and obscure fields that you might characterise as pseudoscience or mind games. It seems our world has returned to the kind of period of the scientific revolution, when Isaac Newton formulated the laws of physics, and yet at the same time was engaged in alchemy and theology. This, incidentally, included his version of the ‘new chronology’ as he reinterpreted the sequence of events in the Bible. Today an objective-scientific view of the world has been called into question for a number of reasons. Thanks to the development of information networks and the democratisation of statements on any subject, the role of expert opinion and expert platforms has been nullified. And the humanities further question the objectivity of science, pointing to its ideological foundations. Technology is developing so fast that people have lost the ability to quickly understand and explain how it all works, which leads to the return of magical thinking and gadgets are perceived as magical objects. In general, reality is floating, as any fact can be declared a fake and vice versa, which is why the term ‘post-truth’ has become popular.

As for art, artistic research has become a major genre in itself, and within this framework artists can investigate anything however they want, the level of speculation in this sphere is simply off the scale. From the point of view of traditional science, for example, any historical constructions that are made within the framework of such art projects, even if they are based on a lot of data and adequate methods, cannot be considered anything other than falsification, because the result is almost always programmed in advance. And this is, of course, true.

All this is nothing new. The real pioneers here are Elena Elagina (1949–2022) and Igor Makarevich (b. 1943), who together and independently incorporated the figure of the scientist into their artistic projects. In 1996 Elagina staged an exhibition at a now defunct Moscow gallery, Obscuri viri, called ‘Laboratory of Great Making’, where the protagonist was Olga Lepeshinskaya (1871-1963), a revolutionary who invented the concept of ‘living matter’ and believed that it was possible to transform non-living things into living matter. She sought to create a means of rejuvenation and a cure for all diseases, and later became an associate of the infamous pseudo-scientist biologist Trofim Lysenko and contributed to the Soviet government’s crackdown on genetics. Elagina depicted her as an adept of alchemy. Together she and Makarevich also addressed another influential character in Russian culture, Nikolai Fyodorov (1829–1903), the creator of Russian Cosmism. In their 2009 work ‘Common Cause’, shown as part of the main project of the 53rd Venice Biennale ‘Creating Worlds’ curated by Daniel Birnbaum, the artists assembled a portrait of the thinker from a number of images. There was an imperial eagle working as a refrigerator: this is not only a literalisation of conservative philosopher Konstantin Leontiev's famous phrase "Russia must be frozen", but also an expression of the dialectical logic of flight of fancy of theorists like Fyodorov, whose thought simultaneously worked both for progress and regression.

In another joint project by Elagina and Makarevich, ‘Unknown Intelligent Forces’, which was first shown in the Louvre in Paris in 2010–2011 at the exhibition ‘Russian Counterpoint’, the artists turned to the figure of the self-taught scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), who, despite his contribution to the development of space exploration, created utopian theories based, among other things, on Fyodorov's fanciful constructs. This work consists of four ladders placed against a wall. Under them lie many pairs of shoes, ostensibly left by people who have ‘climbed’ into the sky, thanks to Tsiolkovsky. Between the ladders, neon letters ‘ChAU’ are burning. Story has it that Tsiolkovsky once saw these letters in the sky, and he wondered what the meaning behind this vision was before he realised that in this shape, they resembled the Latin word ‘RAY’ a combination of letters that can be read again in Russian as ‘paradise’. Such complex hermeneutics point to the uneasy nature of Tsiolkovsky's visionary practices.

In the mid 2010s, Elena Kovylina (b. 1971), who had previously been mostly involved in social performance art, became interested in the topic of breakthrough scientific developments bordering on the supernatural. In 2015 the artist stunned those familiar with her art by announcing that she was creating the exhibition ‘Eternal Time’ at the Iragui Gallery in collaboration with a certain Siberian experimental laboratory ‘Noosvyaz’, which refers to the ideas of natural scientist Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945). The noosphere is a collective network of minds which increasingly covers our planet as mankind evolves. Of course, ‘Noosvyaz’ has never existed but this did not stop Kovylina from claiming that thanks to it she could control time and generally influence the course of things by inducing various thoughts on people. In 2022, the artist turned to new technologies once again in the exhibition ‘Artefacts and Gadgets by Elena Kovylina’ at the All-Russian Museum of Decorative Arts, where she combined new devices like drones and smartphones with mythological subjects. The history of mankind has looped and science has become magic, that was the impression Kovylina's paintings gave.

Pseudoscience has always been a dark companion of science, and the further into history one or another scientist and thinker goes, the more difficult it is to separate one from the other and to understand how these seemingly opposite fields coexist. Art shows us that they can coexist peacefully, drawing inspiration from one another and providing nourishing food for the imagination of artists.