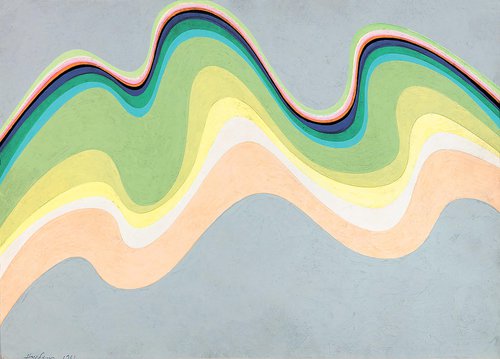

Roman Sakin. The School of Athens. Third room, Bedroom. Courtesy of the artist

Roman Sakin on Making Art for the New Year

Stepping into Roman Sakin’s packed Moscow studio reveals both a skilled artist and a perceptive commentator on art’s ever evolving narrative. From playful sketches to profound installations, Sakin navigates themes ranging from the human perception of space to censorship, weaving a narrative that challenges societal norms while offering a glimpse into a world of artistic resilience. ‘The School of Athens’, his current solo exhibition in Tula, is a tongue-in-cheek take on classical Greek philosophy.

As I enter the cramped basement studio in central Moscow of artist Roman Sakin (b.1976), he is busy working on what looks like the sketch for a poster. “As a teacher with a ton of experience, I decided to make a series of illustrated instructions for aspiring artists,” he explains, adding, “How to be an artist in Russia so that you don't go to jail.” He reels off the subjects which are allowed or forbidden, as we look at pictograms on the two posters, one for painters and the other for sculptors. Flowers, circles, geometric forms, waves, cartoon characters, and human faces are allowed. Explosions, guns, graves, protests, prisons, and same-sex relationships are not. Painters should also avoid a combination of yellow and blue, the colours of the Ukrainian flag. Sakin learnt this from personal experience, when he designed an installation with a yellow-blue façade for the Archstoyanie Land Art Festival last summer, he recalled the organizers sending him text messages saying that “it does not look nice”. At first he did not understand, then it clicked. The posters are a caustic if accurate comment on the current situation on the Russian art scene. “There is a way of resistance to approaching censorship and self-censorship,” Sakin says referring to his instructions. “It turns out, they cannot ban me from doing anything because I am already forbidding myself. As if I have flogged myself. These instructions are more of a forecast of what contemporary art can turn into.” He adds that this process is already underway. All art offered at the nation’s art fairs now looks like that, Sakin observes. As a frequent visitor to these fairs myself, I concur.

Recently, in the town of Tula, some 200 kilometres away from Moscow, he created a total installation dedicated to the Ancient Greek School of Athens which was a remake of a 2015 project in which the age-old tropes of philosophy and learning were spiced up with subtle irony. Visitors wander through a classroom-playground filled with neatly lined-up sandpits and a dormitory with playful ghosts. Yet the bigger and grimmer irony hides in the location of the installation, a most unlikely place for philosophical musings, let alone childish play. Tula has been known as a city of gunmakers for centuries, and the Machine Tools Museum that hosts the exhibition is funded by Rostech, a government-owned corporation producing hi-tech equipment for the army and the commercial sector.

Censorship has never been an issue for Sakin. His pensive, philosophical art somehow manages to remain relevant without immediately echoing the political agenda. “I have never positioned myself as an artist working with current affairs”, he admits. “But when the situation affects you very strongly, you cannot ignore it.” Born in the city of Kursk in the South of Russia, Roman Sakin was trained as a sculptor at Moscow’s Stroganov Academy. Even now, he admits that when he works on his drawings, powerful as they are in themselves, he sees them as sketches for large scale sculptures or installations. Yet, when asked to define his medium, he does not have a clear answer. “I used to call myself a sculptor. But it has become more complicated”. His practice now spans different media, including works on paper, interactive installations, and even philosophical treatises. In an installation called ‘Pivot Point is Me’, he created the illusion that the whole world revolved around a viewer who stood in the middle of it, like a living allegory of the Sun surrounded by circulating planets. Likewise, there is one topic around which his artistic universe revolves. “I work with space”, he explains. “I am exploring how humans perceive it”.

Throughout his career, he has approached this subject from different angles. It all began with his early controllable sculptures from the 2000s, that could be manipulated by viewers. Later, he delved deeper into theory, creating Kuraspatia, his own method of healing. A quirky collection of weird physical exercises, it was supposed to help the user to discover their own “point of space perception” and connect it to a “central point in space”. He tested this system on himself and claimed that it works wonders, comparing the effect with that of popular practices of “mindfulness” such as yoga.

The words ‘explore’ and ‘research’ are overused, and frequently misused, in the art world, and some art publications now even banish them from their pages. Yet for Sakin they still retain their original meaning: to find out and understand. Art is mostly used to create new worlds, he thinks, something he has never aspired to do. He believes the purpose of his practice is “to explore the world as only art can do, not to create new worlds”. During the covid pandemic, he created a series of crude, quirky contraptions. His ‘Smell-o-Scope’ was used collect odours and his ‘Hear-o-Scope’ for listening to the faintest sounds in nature, “the crawling of beetles or the footsteps of ants”. ‘Pocket Gallery’, a box with no bottom or lid, allowed its users to change their perspective and focus on small things by taking them out of their context. “When I cannot understand something, I design a gadget that helps me to understand”, Sakin says. “During the pandemic, I realized that a new era is coming, and for that era, new gadgets are necessary.”

His art really possesses powers that science does not have, and there is a place in it for humour and ambiguity. His biggest project to date, ‘Dream Sanatorium’ at the outdoor Archstoyanie festival in the summer of 2023, was an immersive installation-performance complete with comfortable beds, relaxing ambiance, soothing music, and boring lectures. At first glance, it was the epitome of wellbeing. Yet, according to Sakin, the project was not straightforward and there was more to it than letting visitors catch up on their sleep deficit. “It could be perceived as a critical commentary about a government that lulls you to sleep, or of finding refuge in the world of dreams”.

In the violent world of today, there is scarcely a place of refuge anymore, besides the world of dreams. Since 24th of February 2022, the day when Russian troops entered Ukraine, Sakin and his family have tried to live in Turkey, Georgia, Armenia, and Israel. There was a sense that war followed their footsteps for they had hoped that Israel would ultimately become their new new home. They returned to Russia when the war broke out there. Like many artists, Sakin felt out of place abroad, so he does not regret coming home. Does he believe that art can change the world for the better? It seems not. “It’s not about changing, it’s about healing”, he stresses. A painting or sculpture will never change anything, it requires a more comprehensive approach. “If I were to offer people a system within which they could live, maybe that would make a difference”, he says. Unusually for an artist, his mind works systematically even in the most stressful of circumstances. One of his latest installations, unveiled at Cosmoscow fair last Autumn only to be sold to collector Anton Kozlov within a few hours, is called ‘Universal Box of Russian Art’. It is a large wooden box filled with small artworks, divided into four sections according to theme. As Sakin says, the circumstances in Russia are more or less the same, so it is very easy to prepare in advance relevant, topical artworks for any occasion. The artist’s explanation of the installation runs as follows:

“Universal box of Russian art, which can be used infinitely, in a circle as a calendar.

1. The art of senseless war and senseless sacrifice

2. The art of change and revolution

3. Art of prison camp and underground

4. Art about the New Year”

As I climbed up the stairs, leaving Sakin’s basement, I felt inexplicably grateful. While there is humour in the art world or the world at large, there is still some hope.

Roman Sakin. The School of Athens

Creative Industrial Cluster Octava, The Museum of Machine Tools

Tula, Russia

July 27 – November 4, 2024