Lev Nusberg. Wave in a gray-magnetic field, 1961. Tempera on paper. 31,4x43,7 cm. Courtesy Anton Kozlov collection. ‘Future Lab. Kinetic Art in Russia’ exhibition at the Manege

Two versions of a movement: kinetic art in St.Petersburg

Two major feuding exhibitions in St.Petersburg deliver alternate visions of kinetic art. The resulting tension throws a greater light on the movement than either show could have done alone.

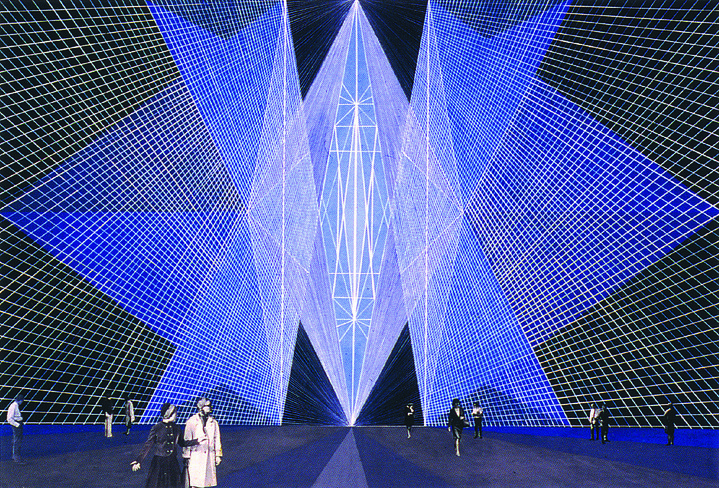

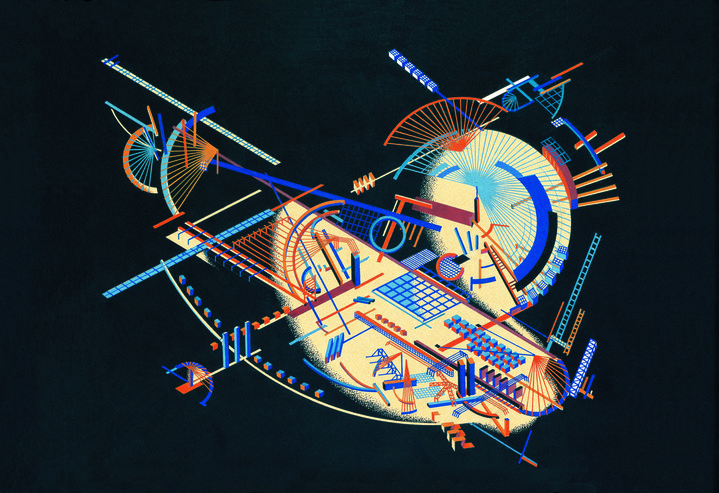

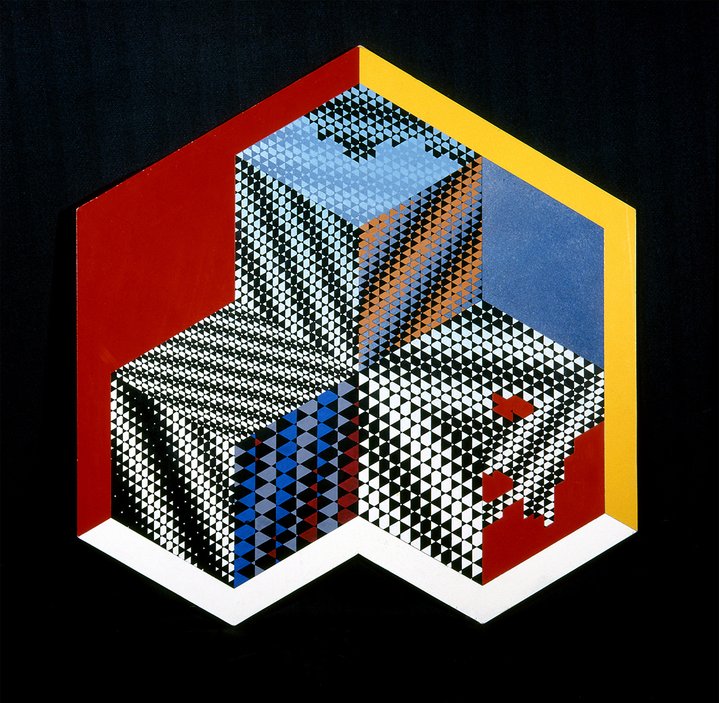

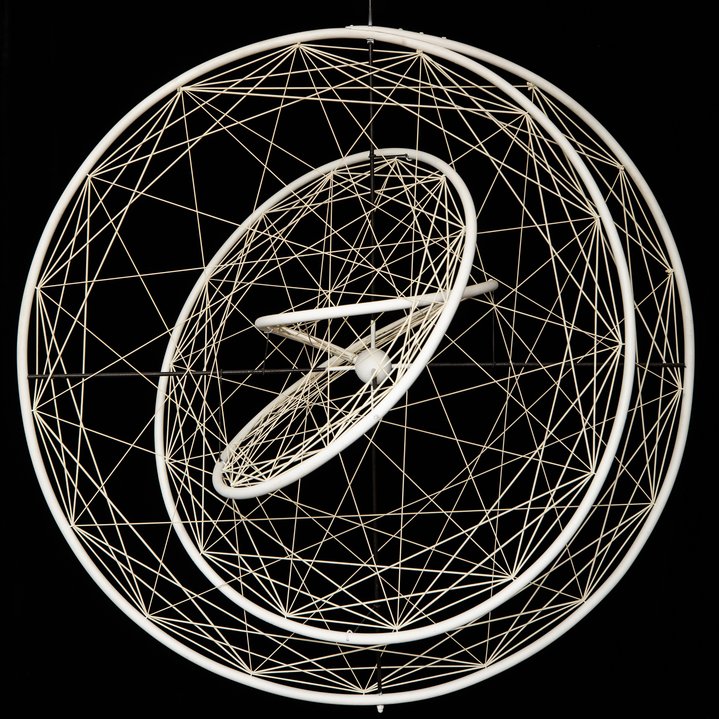

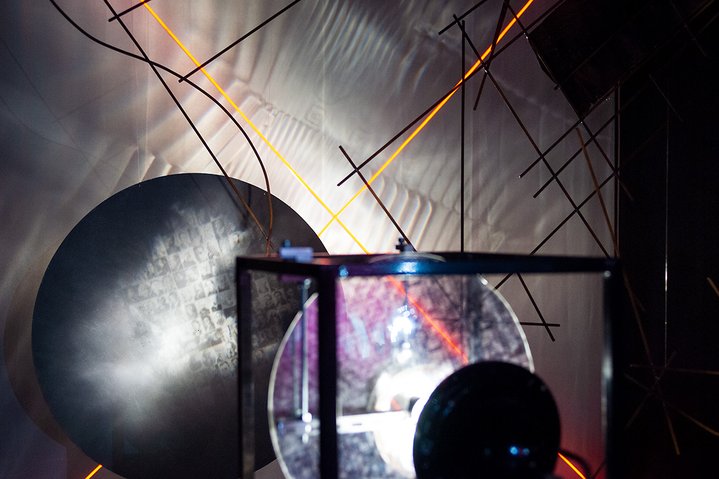

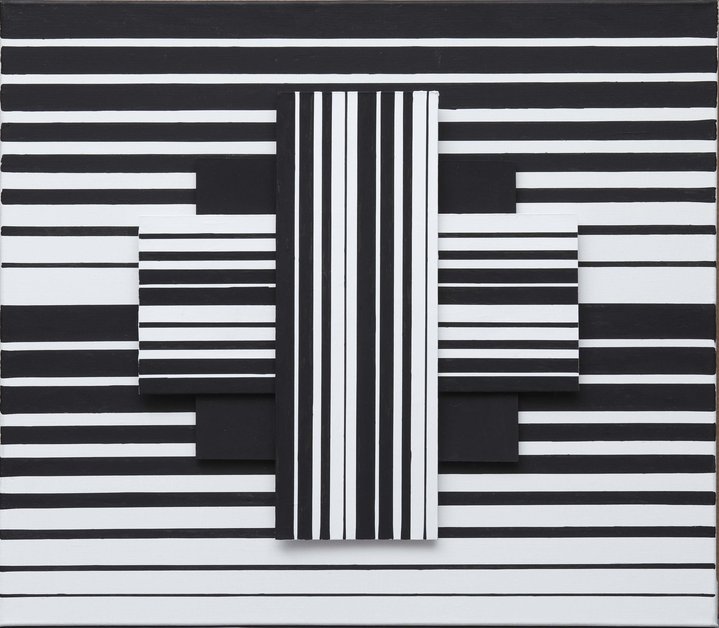

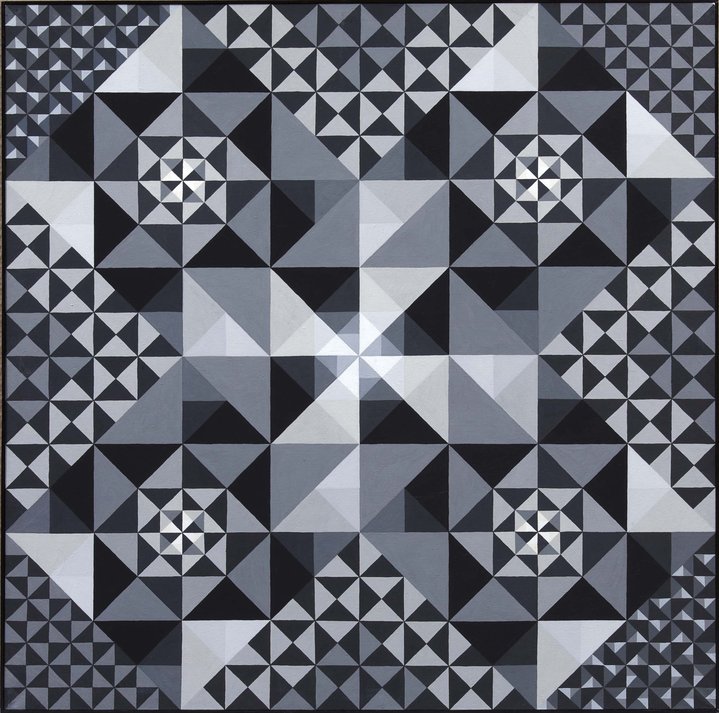

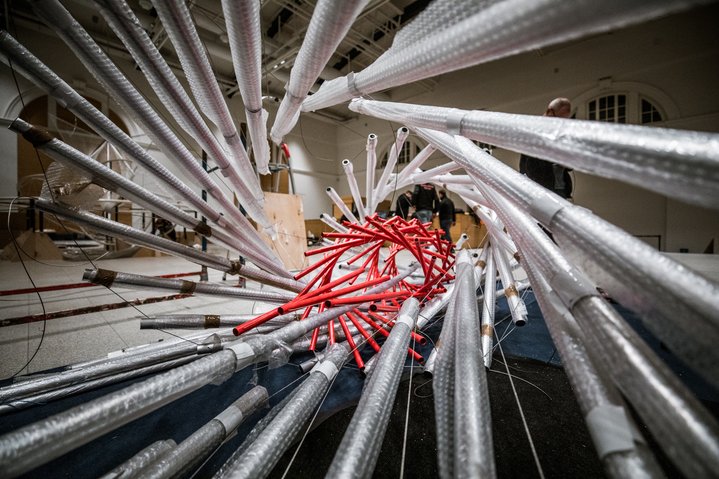

Through February and March, walking into St. Petersburg’s Manege Central Exhibition Hall is not unlike finding oneself on the set of a Soviet science fiction movie. Moving geometrical shapes hang on wires, numerous sculptures seem lifted from alien command centres and an eerie, harmonious soundtrack produces the impression of drifting through space. This is the atmosphere of ‘Future Lab: Kinetic Art in Russia’, an exhibition focusing on the Post-War Soviet artists who formed the Movement group, dedicated to exploring the implications of motion on artistic practices. While the first piece of kinetic art is often claimed to be sculptor Naum Gabo’s (1890–1977) ‘Standing Wave’ (1920), it wasn’t until painter and sculptor Lev Nusberg (b. 1937) formed Movement in 1962 that the wave distinguished itself from the earlier Constructivist endeavours of the early 20th century avant-garde.

Movement’s manifestos are plastered across the walls, sifting quotes from forefathers like Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) with those of major figures like Viacheslav Koleichuk (1941–2018), Francisco Infante (b. 1943) and more, all of whom have painted, sculpted and created installations. The positivist-leaning texts express optimism and a thirst for progress that harks back to a time when utopias were thought to come as the result of unregulated mechanical prowess. The exhibition hall only adds to the atmosphere. The gaping spaces surrounding the exhibition structures make the contrast between stasis and movement more acute. The sheer amount of pieces on show, especially given the narrow theme, creates claustrophobia. Viewers rub shoulders while passing through the Manege’s narrow side-hallways, embodying the friction expressed by the canvases, sculptures and videos.

But this is not the only exhibition about the movement that opened in the city this past February. The mind behind the original exhibition was Polina Borisova, curator of 2017’s ‘A Perpetual Motion Machine’, displayed in Vladivostok’s Zarya art space. It was the first exhibition to reflect the entire history of kinetic art in Russia, and Borisova hoped to bring the show to the Manege in St. Petersburg. However, Borisova was eventually removed from that exhibition as its curator and therefore opted to create a parallel show, ‘The Form of Movement’, in the gallery at the city’s Sevkabel Port. Much like Zarya in Vladivostok, Sevkabel was a dilapidated building complex before being renovated into a cultural space. The port now includes a cluster of hipster eateries, cafes, a skatepark and, in winter, a skating rink facing the Gulf of Finland. The gallery space hosting ‘The Form of Movement’ is located above the expansive skatepark, and to fill it, Borisova ran an open call that resulted in a line-up of artists significantly younger than those displayed at ‘Future Lab’.

The pieces range from installations reminiscent of the Nikola-Lenivets park (which hosts the Archstoyanie art festival often described as Russia’s Burning Man), a night table that dances when you wave at it, a sphere of interconnected components that moves, like liquid, when you apply pressure, apparati with moving pieces that fail to work over time. All of which ask questions of our expectations for perfect order in a world where physics, though consistent, doesn’t always work the way we might like.

While the pieces at ‘Future Lab’ create a consistent atmosphere, the mood at ‘The Form of Movement’ changes as viewers walk through the hall. Elements of ‘Future Lab’s celestial vibe make their way into particular installations. A back corner basks in the glow of wooden sculptures lit by yellow lamps, offset by pale screens. A video in which a long-haired woman is whipped in the face by a bunch of nettle, by the feminist art group Nezhniye Babi (“Gentle Women” or “Gentle Chicks”), though visually compelling, is disturbing when presented without context.

‘The Form of Movement’ has less pieces on show and tends towards expansiveness over ‘Future Lab’s buzzing claustrophobia. The Manege offers a darkened room full of sci-fi ambience, as if the whole affair takes place in a bubble moving through the cosmos. In Sevkabel, light comes through large, gritty windows and throws the rose-coloured mounts into a warm array. ‘Future Lab’ exists in a timeless isolation, while ‘The Form of Movement’ is suffused with noise from the skaters below, themselves visible through a hole in the ground – they are like a spontaneous installation themselves, adding up to a living, contemporary atmosphere less divorced from the world around it.

These are, ultimately, two stories of movement. Much ink has been spilt on the scandal that led to the parallel exhibitions, and there are many claims as to who is to blame for Borisova’s split with the Manege. But the result is two opposing poles that cast light on each other, and much like with magnetism, each pole is less comprehensible without the other, much like the play of line and colour, shape and formlessness, light and dark.

In the end, the social tension that has, for the moment, divided St. Petersburg’s artistic community matches the physical tensions celebrated by the very artists both exhbitions feature. It’s the tension of tide, orbit and divers about to launch from their boards. Destructive of course, and sometimes unpleasant, and certainly something that should be avoided the next time around, but this is nevertheless undeniably illuminative, fertile and abrupt. It is not an unfit legacy to the artists who themselves sought to fuse art and technology, space and substance, stasis and movement.

Future Lab: Kinetic Art in Russia

Manege Central Exhibition Hall

St. Petersburg, Russia

14 February – 29 March 2020

Forms of Movement

St. Petersburg, Russia

21 February –5 April 2020