Pavlov, Braille and Jazz in the world of Alexander Ney

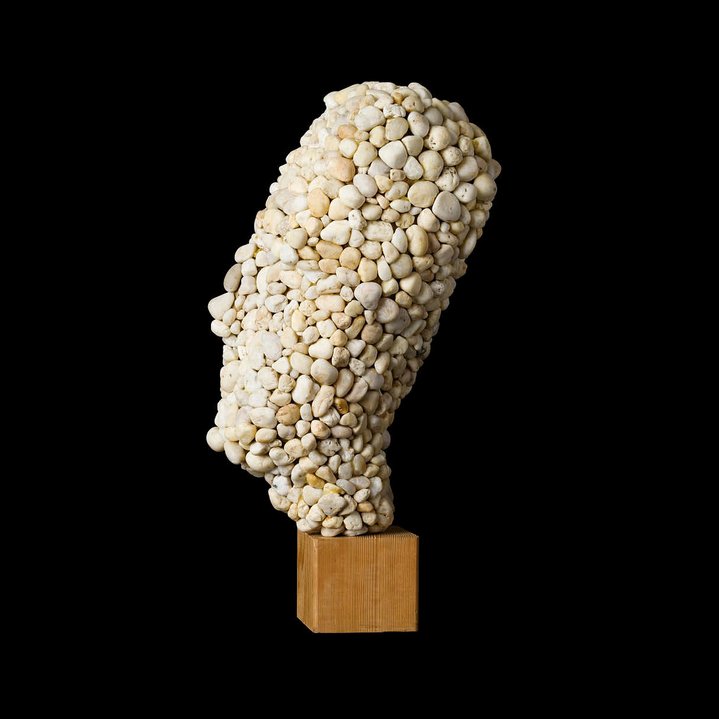

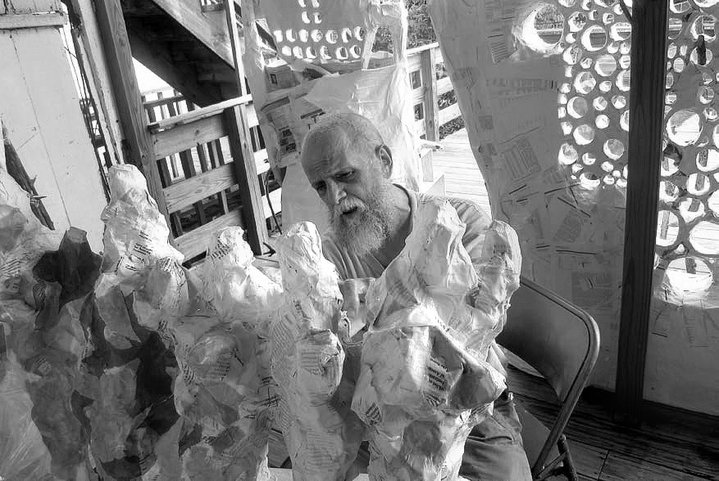

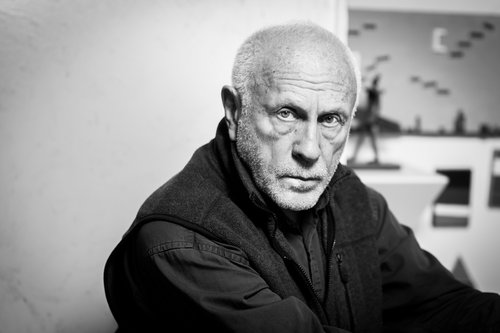

This non-conformist sculptor who has created a singular artistic legacy over six decades is best known for his perfectly executed hollow terracotta sculptures made by hand in a repetitive and controlled technique he pioneered and in which he is still working today at the age of eighty-three.

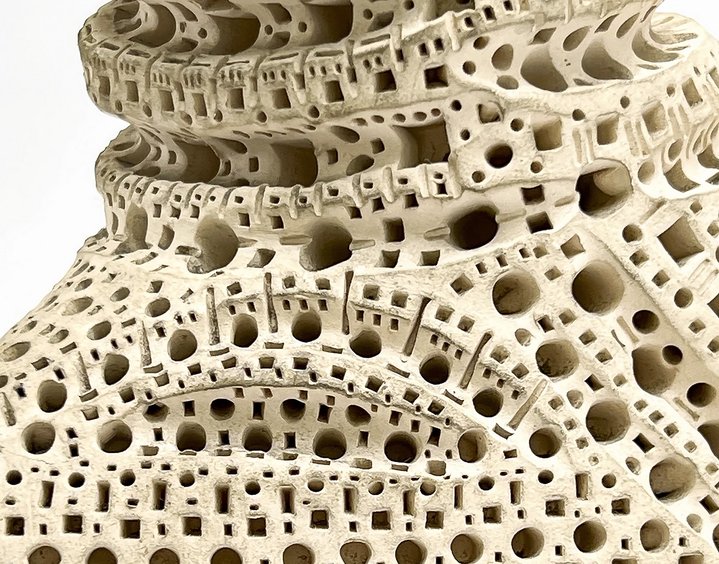

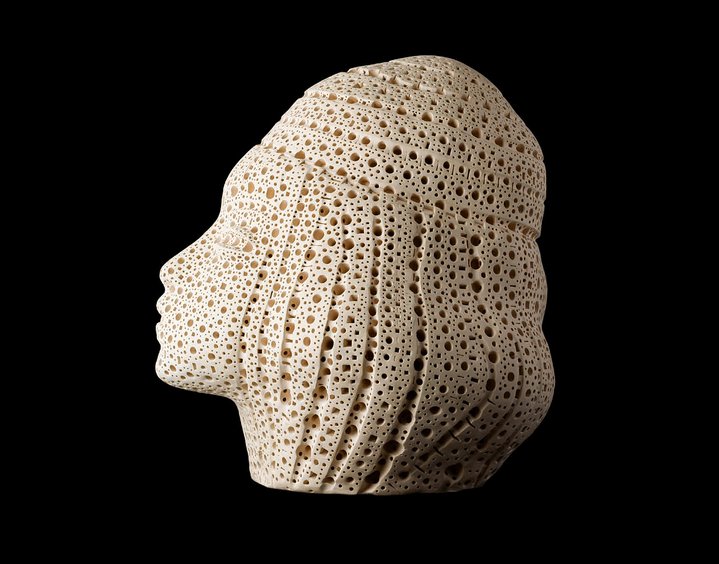

The ancients loved terracotta, it was easier to mould than stone and despite being porous it is extremely durable, and widely available. The iron in it gives the earthy ochre or redish colour. It is a medium associated in particular with Russian artist Alexander Ney, born Nezhdanov (b.1939). Many of Ney’s sculptures are appropriated from pre-classical art, their simplified forms, elongated and exaggerated. A Ney sculpture is always hollow, and punctured all over with tiny rectangular and circular holes. There is something Kusamean about these repetitive holes, the artist’s urge to cover surfaces with repeated patterns - over decades – a compulsion, the taming of one’s anxieties perhaps? I decide to visit him while on a trip to New York in part to find out about these holes as much as get a glimpse of the man behind them.

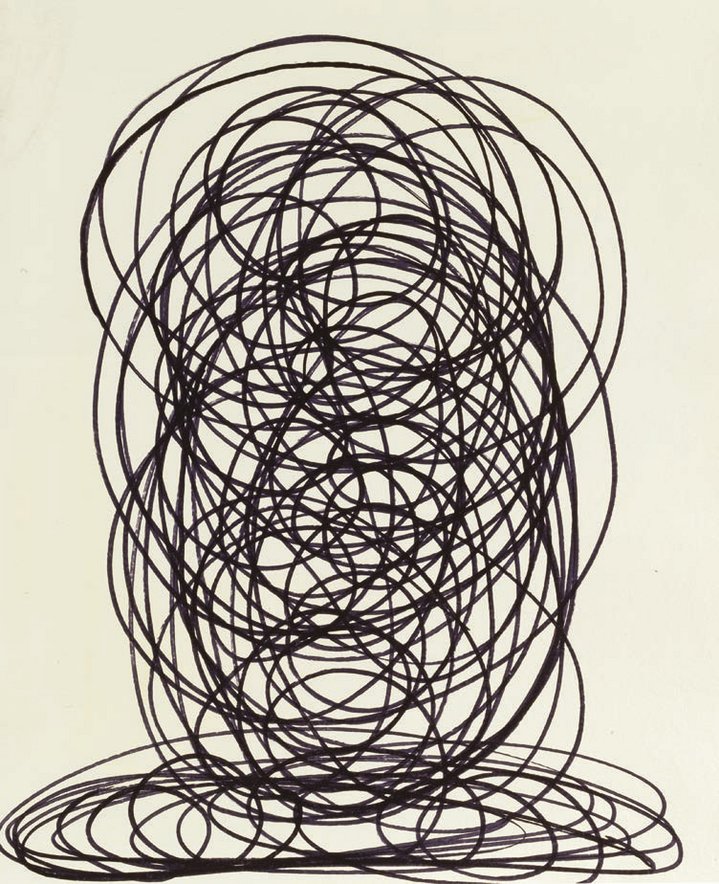

Holes or absences are a kind of presence, wise people tell us what you do not say is more important than what you do say. Martin Luther King put it in political terms about what your friends do not say. In Ney’s sculptures of birds, women, musicians and heads, the little holes and the hollowed out insides are as material as the clay itself. This is nothing new - modern European sculptors such as Henry Moore (1898–1986), Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) and later Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002) went down this line, exploring space and volume. But as a post-modern Ney is not interested in formalism per se and he boldly appropriates ready made images and styles like the Pop or Sots artists did, lifted not from contemporary life but from ancient art. Ney was searching for something deeper, ancient art is all about Gods and the spiritual and he mines the past like an archeologist, in his imagination the search for the spirit takes him into the realm of the cosmos, with its unifying laws and mathematical formulas. Empires have risen and fallen as he punched his little holes in clay over a life time. He cannot say what drives him other than: “I am not an artist, I do it because I don’t know what to do”. This guides his whole approach, he sees perforating the sculptures as a kind of automatic writing.

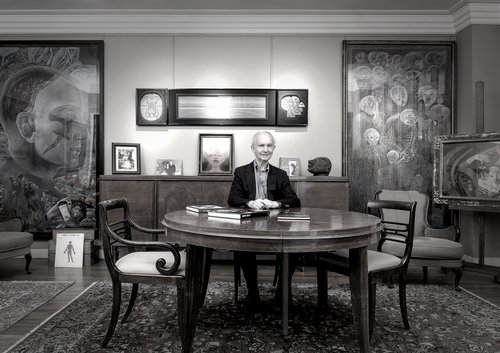

There is a very selective market for his art today, although his instantly recognisable body of work made over a life-time, is striking enough to become a brand. I meet him at a crossroads in life, where he has recently moved into a new apartment in Long Island City and there are talks of converting a garage into a cultural centre dedicated to his life’s work. This task lies on the shoulders of his son Joel Ney who is dedicating his life now mostly to sorting out his father’s legacy. He worked some years at the New York Times and was involved in other projects, but realised he needed instead to focus on a task closer to home, when “I stopped assisting my father and things started going haywire”.

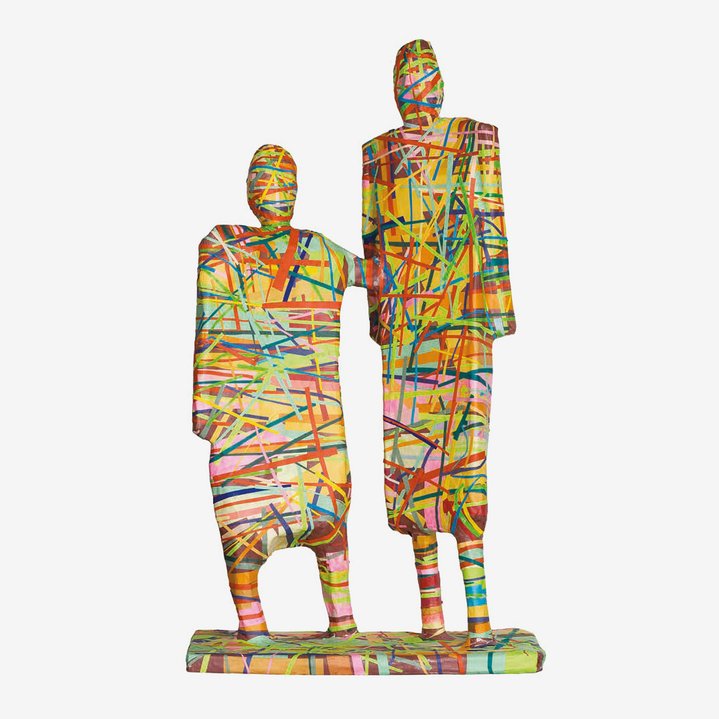

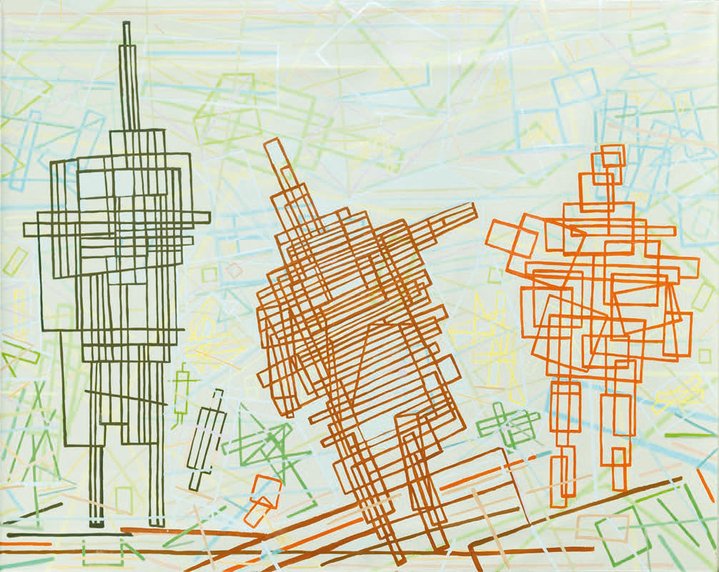

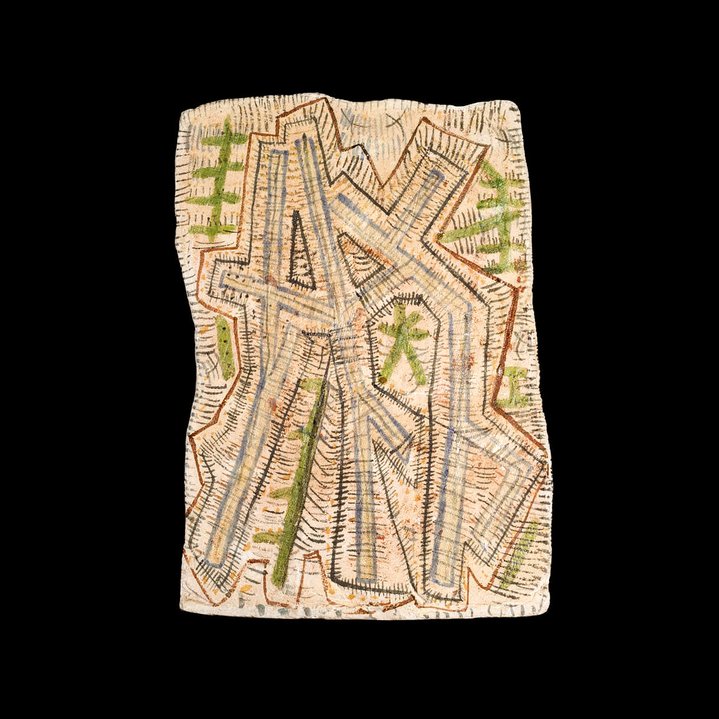

Together father and son have a tall order, when I meet them they are surrounded by a kind of tidy chaos. It is a bright morning, we are sitting in a tiny, cramped space with kitchenette in the background, in a new development in a trendy area of Manhattan, close to MoMA PS1. Floor to the ceiling is packed with his small scale sculptures hidden under a shroud of sheets (terracotta does not work well in large dimensions although he has done large scale commissions which he likes as they reach bigger audiences) and there are his paintings too, brightly coloured fractured repetitive marks covering the surface. We are high up on the 6th floor, entirely surrounded by similar glass buildings, the windows all reflecting back, bright, light in my mind, the windows echoing the repeated holes in a Ney sculpture.

As an artist, Ney sees himself as an outcast, certainly not a revolutionary figurehead. His was an unsettled childhood, his mother passed away when he was a boy, eventually he was brought up by his aunt, a disciple of Pavlov, and he started to study art in earnest when he was in his early teens. He found his feet in Moscow during the Khrushev era, he recalls a feeling of spring and optimism in the air at that time. Art critic John Berger wrote how the English landscape painter JWM Turner’s father was a barber and that in his son’s late canvasses his use of white came from memories of his father’s shaving cream. Ney’s father was a talented singer, had a deep voice and Ney talks of how his father filled his lungs with air. This element, air, comes up many times throughout our conversation. For example, it is not to spaces or voids that he refers when talking of Moore’s sculpture but ‘air’, and how Moore’s art “is a form of language almost like braille”. He says artists need air to breathe. Maybe he feels his father’s presence or breath lingering in the spaces he creates. After his mother’s passing, the relationship between father and son had marred by his father’s new partner, who did not bond with Ney. It must have been a painful time for him.

Eventally, in 1972, Ney left the Soviet Union. First he went to Nice when the South of France was politically and culturally communist and socialist, somewhat still under the influence of Picasso. Looking back, Ney calls it today a fairy-tale country. But then a challenging sejourn in Paris at the Cité des Arts, convinced him to leave, the American artists he befriended there, Elaine de Kooning (1918–1989) and Robert Motherwell (1915–1991) who could see that he was a fish out of water told him to go to the USA instead. He had come to France using money he had made together with his wife, also a sculptor, on a joint state commission they had been given to make a sculptural portrait of Lenin. A commission for which they had been well paid. He smiles as he tells the story thinking about the ironies of Lenin funding his escape from Soviet Russia.

It was a prescient step as his contemporaries, Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023), Leonid Sokov (1941–2018) and Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013) emigrated a decade later, and in 1970s New York, Ney was something of a curiosity invited to speak on ‘Golos Ameriki’ which gave him visibility. American collector Norton Dodge bought his work. He embraced elements of American culture, especially Jazz music, and how although it was frowned upon in the Soviet times, Duke Ellington’s music was actually all about soul, coming from the harsh conditions of slavery and the music was “about overcoming all that”. It was a triumph over austerity not a debauched celebration of capitalist waywardism, it had noble roots.

He talks in long monologues, he has evidently thought carefully about giving me a chronological history of his life, with anecdotes, he leaps about a bit but in general it is clear and I busily note it all in my book. But I want to stop him too. I think of silences. I interrupt his flow, his anecdotes, and find the courage to ask about the repetitive holes in his work. He does not answer me at first, maybe I ask him three times persisting, and he does not answer, Joel steps in to remind his father. He remains silent. Artists do not like explaining away their deepest secrets. But I badger once more. “It is like a poem”, pushes back Ney, “I cannot explain this in a moment.”

I stop asking. Then Ney goes back to air: “In a yacht you can sail against the wind, change the sail. In life take it the right way. When you lose art it still stays somewhere. The cosmic mind keeps it all … life is a lesson”. I think about how artists must experience a feeling of loss sending their art out into the world over decades, pieces lovingly made, scattered all around, disappearing into the ether. He turns his thoughts to what bothers him, what remains unresolved: “This life is a study to be perfect, I made a lot of mistakes” But things take a darker tone as he suddenly says “when you speak you are punished. Walls can hear you. I am afraid to say anything. I must learn to be better”. I understand immediately that this is Ney once again as a child back in the Soviet Union of the 1940s, past traumas decades on still a wound in his present, they have not gone, the legacies of a tough childhood in an autocratic regime and a broken family. He was two during the Siege of Leningrad, that he survived at all is a miracle.

Emigration had its own challenges, “I lost everything when I came to the USA” he says, but inspite of all these hardships he has overcome, he finds solace in the sense that he has lived an authentic life. “There is one Ukrainian Jewish mystic who said ‘I like sincerity’. A man with a hollowed out face, he becomes his own work”. It is that thing people often say, of living a good life and how you can see it on someone’s face. Perhaps sculptors understand that better than any of us.