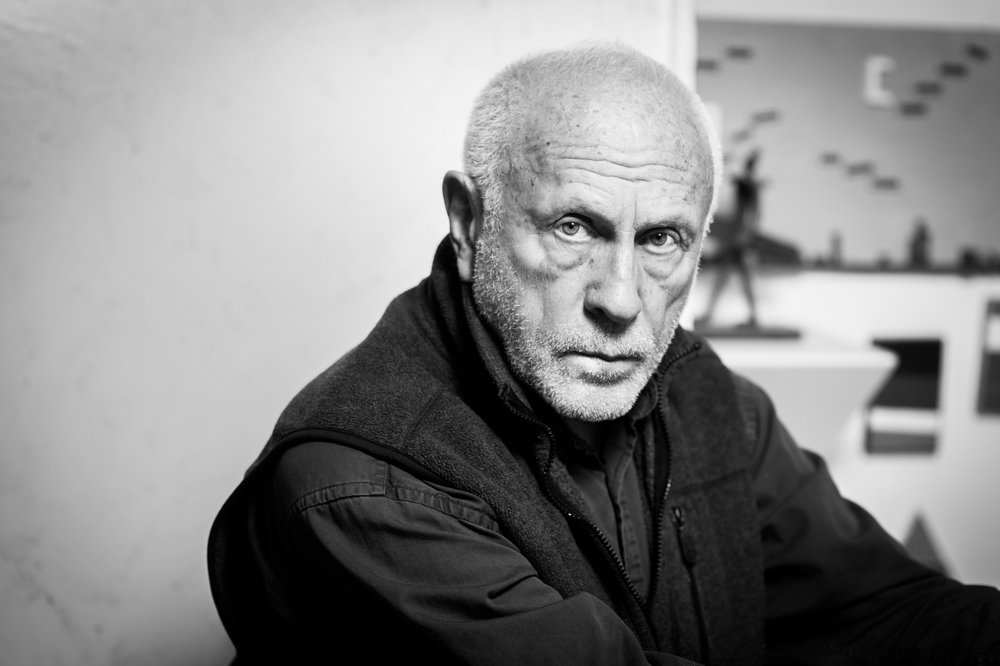

Igor Shelkovsky: a Russian sculptor whose limit is a ceiling

Igor Shelkovsky, the artist who launched a journal that brought the attention of Western art experts and collectors to the art hiding behind the Soviet Union’s iron curtain.

Igor Shelkovsky is an artist who knows his limits. This is not to say that he limits himself. He is on the contrary acutely conscious of the restrictions imposed on artists by themselves, the states and institutions they live under, and even the spaces in which they work. He has in many ways dedicated himself to eliminating those barriers.

This profile celebrates the three large-scale permanent sculptures of this Robin Hood among Russian artists, set to be unveiled at the State Tretyakov Gallery on October 7. This unprecedented step in the artist's career is thanks to two generous Moscow gallerists and collectors, Alina and Dmitry Pinsky, who run Palisander Gallery (and currently represent Shelkovsky) and bestowed these monumental sculpture as a gift to the Tretyakov.

Born in Orenburg in 1937, it didn’t take long for Shelkovsky to discover the terrible might of the Soviet state first-hand. Before he was born, his father, a journalist and editor for a local Communist Party newspaper, was arrested and executed. His mother was arrested soon after as the wife of an Enemy of the People, and he was sent to live with his grandmother in Moscow, staying in their communal flat throughout the German bombardments once war had started.

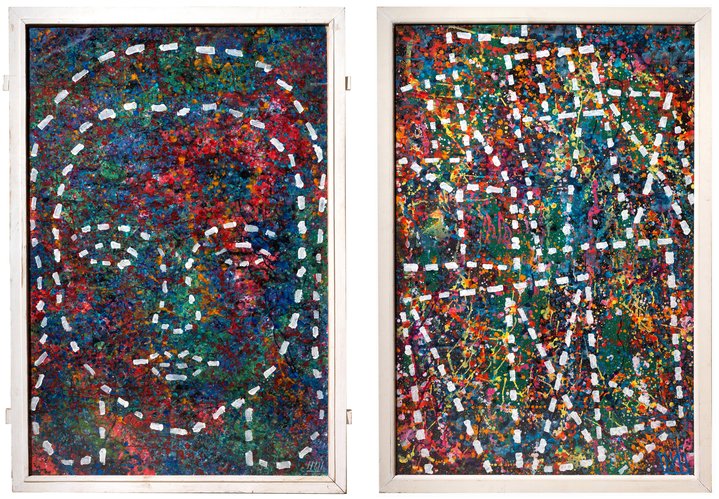

A short career as an icon painter and theatrical set designer eventually led to him working as a sculptor, alongside such legends as Boris Orlov (b. 1941), Dmitry Prigov (1940-2007), and Alexander Kosolapov (b. 1943). Shelkovsky managed to smuggle his work abroad with the help of German and Swiss exchange students in Moscow.

On an invitation from his wife at the time, he left the Soviet Union in 1976 for Switzerland, and eventually claimed political asylum in Paris.

Ultimately, it was not his own art that originally made Shelkovsky famous. On a suggestion from a Swiss businessman, he started a journal called А–Я (in Russian, A–Z), which published works by Soviet artists and writers in the West.

In just eight issues, he managed to publicise over 50 artists, introducing the Western world to figures ranging from the art critic and philosopher Boris Groys (b. 1947) and the writer Vladimir Sorokin (b. 1955) to the artists Ilya Kabakov (b.1933) and Erik Bulatov (b.1933).

He jokes that later, one collector said to him at their first meeting, “Well, you must not be very famous — you were never published in А–Я.” This was true: Shelkovsky never published his own works and spent all the money he received (be it from sponsors like the collector and museum director Dina Vierny (1919-2009) or the sale of works by other artists) on publishing the journal.

In 1985, when the journal published its 8th issue, the inevitable happened: the Soviet government revoked his citizenship. That issue, dedicated to literature, would become А–Я’s final and unquestionably most controversial one. Artists had even started sending letters (under KGB pressure, Shelkovsky is sure) asking not to be published in А–Я.

Nevertheless, Shelkovsky achieved his goal: collectors had taken an interest, artists were emigrating en masse and, he jokes, the Soviet Union was falling apart — all thanks to him. His citizenship was later restored by Gorbachev in 1990, alongside the Nobel Prize winners Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) and Josef Brodsky (1940–1996).

Shelkovsky the artist long took a backseat to Shelkovsky the publisher and emigré art activist. Nevertheless, sculpture remained an integral part of his life. The French government gave him a studio 30 kilometres outside Paris in a former monastery. He returned to Russia in the Perestroika years and created a second studio in central Moscow.

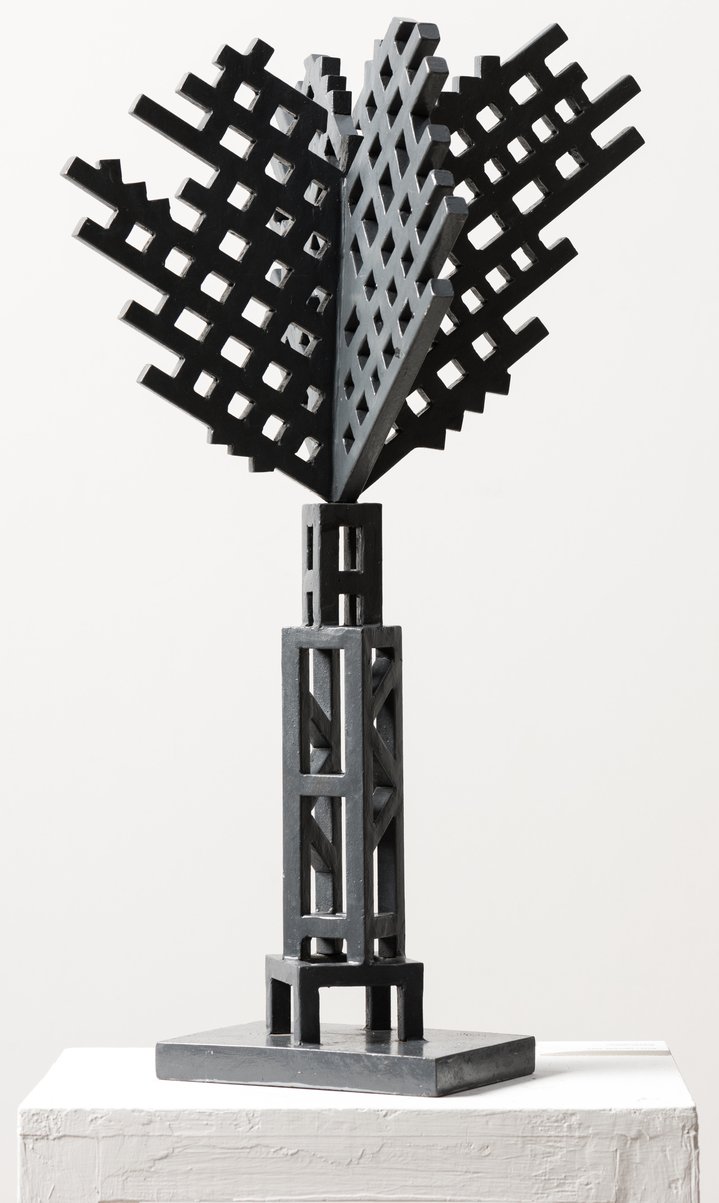

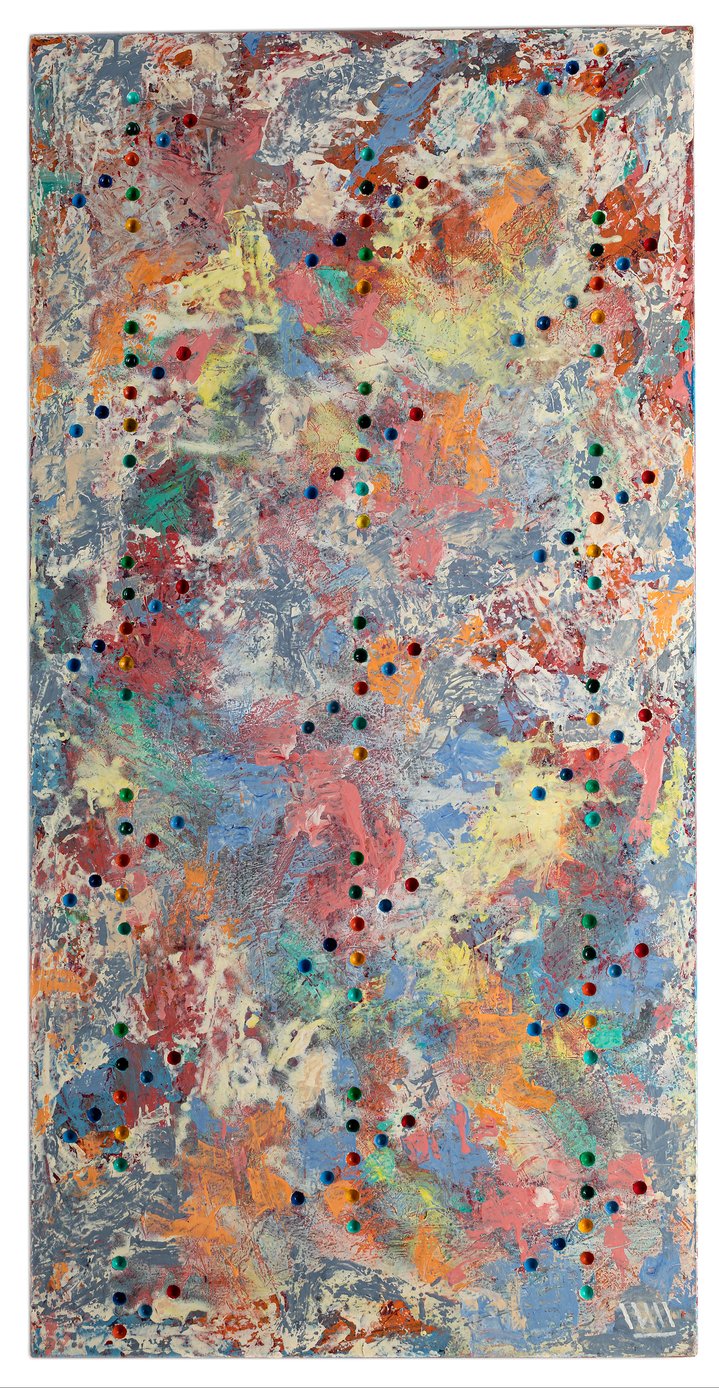

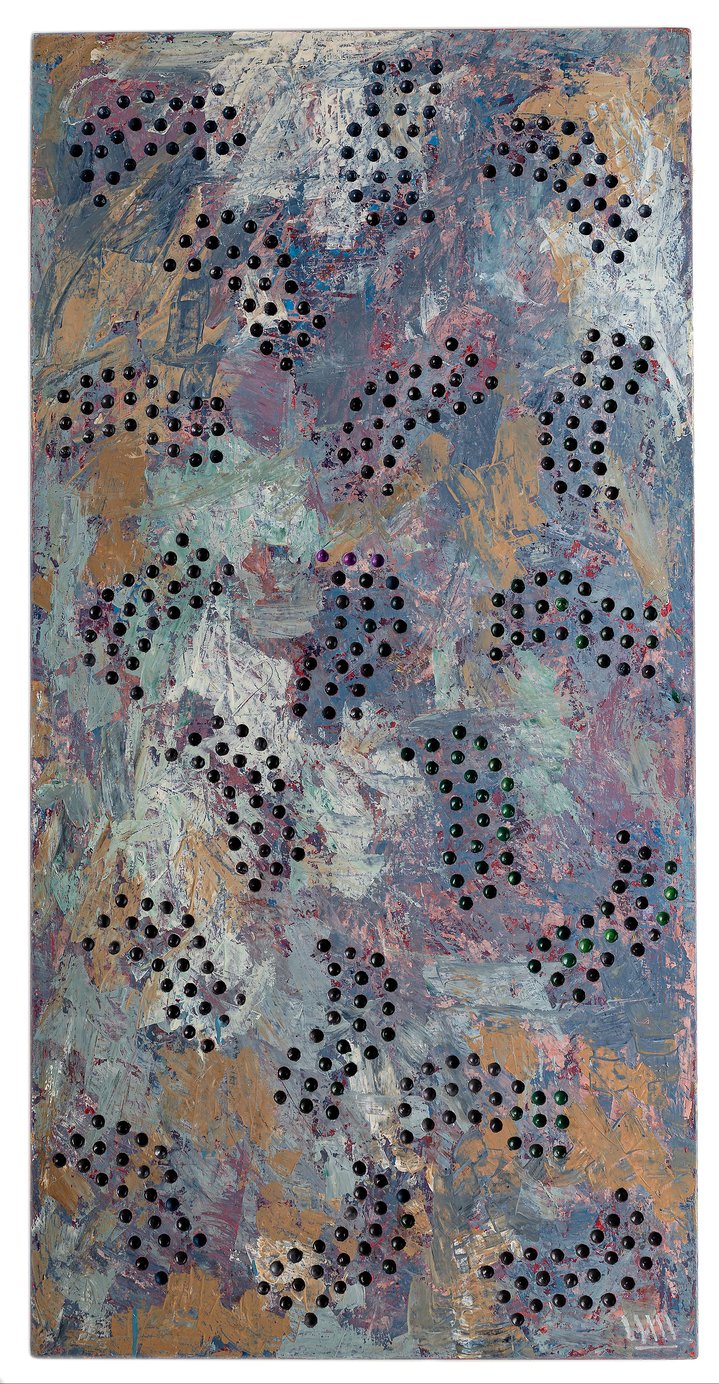

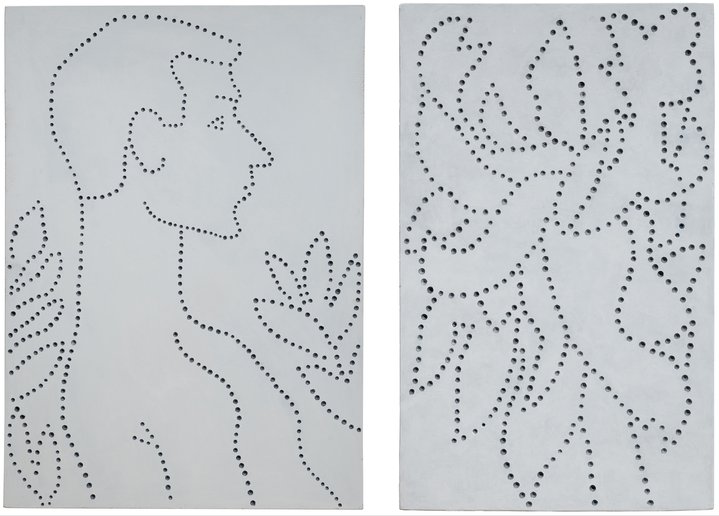

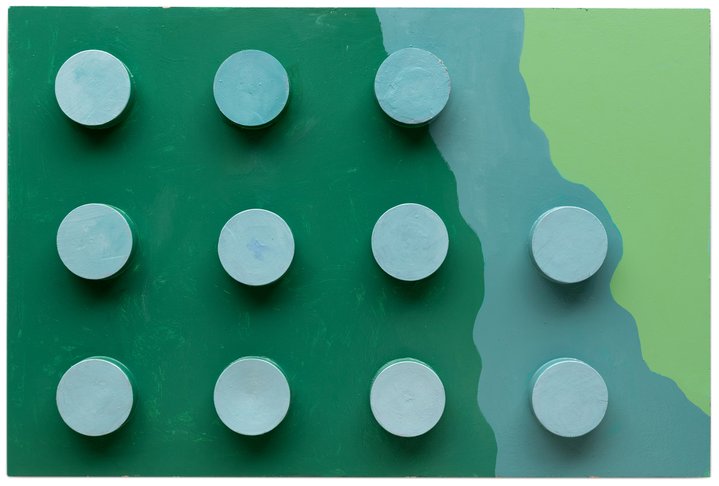

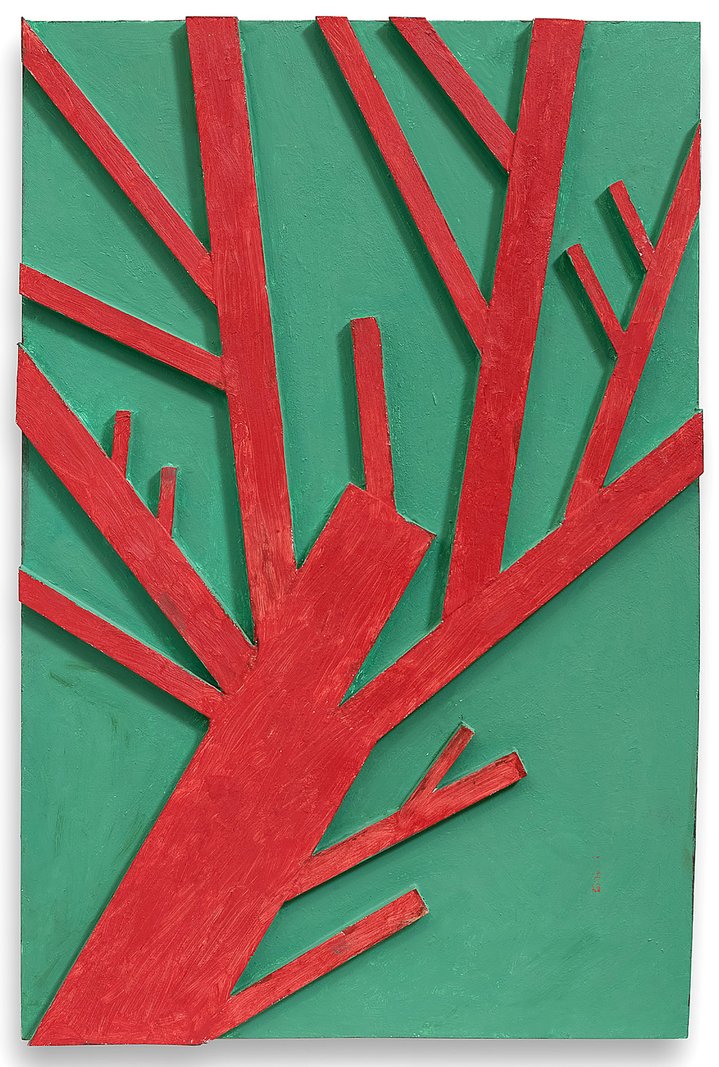

The Paris and Moscow studios are now full to bursting point with his signature works: wooden and metal figures that effortlessly rise into the air, capable of encompassing enormous space without ever feeling massive.

Alina Pinsky describes them as follows: “drawings in the air. [...] They are monumental, and initially imagined as full-size. Shelkovsky sees his wooden forms as prototypes of what he will do in another, more durable material in a different scale in the future.”

Shelkovsky himself says, “I don’t care about material; what matters is volume.” He is not categorical about the choice of wood versus metal: “if you keep it away from the rain and nobody knocks it over, wood will last just as long [as metal] under a roof” — although he admits that several times, his works were knocked over at exhibits. But, he shrugs, “I’m used to it. I just glue them back together.”

Shelkovsky treats the challenges of studio work with dry realism: “Your limit is the ceiling. I just don’t have any space left to work.” He contrasts himself with artists like the sculptor Richard Serra (b. 1938), although he is deeply conscious of the independence that the American’s chosen scale gives him. “He (Serra) can’t even move [his sculptures], never mind pick them up. You need a whole team of people — who cost money.”

In spite of his prolific output, Shelkovsky has never sought out buyers and collectors. Instead, he lets galleries and museums come to him. He refuses to play “the money and fame game,” as he calls it, but at the same time, he understands its root cause perfectly well. When we spoke, he recalled a favourite anecdote: “Rachmaninoff wrote that one pianist faded away and left music entirely because he didn’t get much applause at concerts.” But he tells it without the slightest hint of irony.

Speaking about А–Я he said: “The journal replaced exhibits for these artists. They could see their work in the company of other artists, and be happy that it was reaching more than 3 or 4 of their friends at home.”

Although the fight for buyers and aggressive self-promotion are more present than ever, he is quick to point out that an artist can only exist in dialogue. “An exhibit for an artist is like a mirror for a woman,” Shelkovsky quips. “Without it, they can see neither their features nor their flaws.” By this measure, Shelkovsky has thankfully not lacked opportunities for self-examination, especially in recent years. On October 7, he will have one more, in the New Tretyakov’s courtyard as part of the museum's new public art initiative, inspired by cultural historian Inna Krymova — this time, set to remain in place as a permanent installation.

State Tretyakov Gallery