In Max Sher’s Book, Snow Covers all Traces

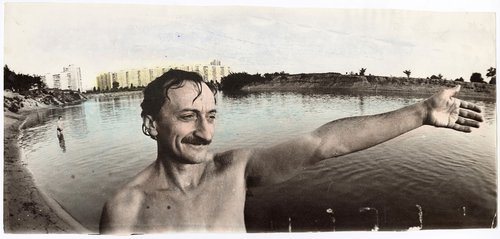

Max Sher. From the book ‘Snow’. Courtesy of the artist

In his new book ‘Snow’, Russian-born photographer, visual artist and critic Max Sher (b. 1975) digs into the past and present of Kars, a geographical region that for centuries has been disputed between imperial powers and has become a backwater in the 21st century.

‘Snow’ is the sixth book by Sher. Shot exclusively in and around Kars in Eastern Turkey – formerly Western Armenia – it relates back to a book project he made in 2009. Sher recalls his “genuine interest in the area arose after reading the Nobel-prize winning novel ‘Snow’ by Orhan Pamuk. This book was so vividly ‘visual’ that I wanted to go there and photograph it. I also wanted to challenge the unspoken hierarchy in international photography that even as a novice I already felt about who can photograph what, and what is expected from a photographer if s/he comes from a certain region.”

It was an era when it was normal for an aspiring Russian photographer to travel anywhere in the world and shoot a self-funded project. Timing was just right too – coinciding with a short-lived political thaw in Turkey and expectations of a kind of diplomatic normalization with neighbouring Armenia, and Sher was able to work freely in this borderland region which has long been militarised. But he says: “Pamuk’s book was really an inspiration, but it rather served as a starting point. Yes, thanks to my friend, anthropologist Zeynep Sarıaslan whom I met while in Kars and who wrote a great essay for my book, I was able to discover more places mentioned in the novel, and it's always fascinating to follow in the footsteps of a great writer. However, I knew I did not want to make illustrations for the book however great it was.”

So, what was or is Kars and why is it important? Orhan Pamuk used the place as a political metaphor for modern-day Turkey. The word itself is similar to ‘kar’, which means snow in Turkish. His protagonists spend three days in the town which has been blocked off by heavy snowfall to carry out investigations. While it is clear that the writer spent time there, the town in his description is largely fictional. The snow is present, and there are ski resorts in the nearby mountains, a popular destination for local tourists, but that is where the similarity ends.

Kars was founded around the 9th century and served as the capital of two Armenian kingdoms – one of its most notable buildings still standing today is the former Armenian cathedral Surp Arakelots (Holy Apostles) built in the 10th century and now the Merkez Kümbet Mosque. Kars became a part of the Byzantine Empire in the 11th century, later captured by Seljuls, then by the Kingdom of Georgia in the 13th century, then eventually by the Ottomans in 1514. It was strategically important located on the trading routes between Persia, Caucasus and Anatolia. After multiple attacks by Persia in the 18th century it became a point of interest for the Russian Empire in the 19th century following its push south across the mountain ridge. It was here that the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin caught up with the Russian army to venture further West and witness the taking of Arzrum (now Erzurum), which he described in ‘A Journey to Arzrum during the Campaign of 1829’. Still, it was not until the taking of Kars during the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war and the treaties that followed leaving it under Russian ownership, that a Russian province, called Kars Oblast, was formed, the term implying a direct military management that co-existed with the local indigenous courts. During the first two years of Russian rule around 75,000 Muslims left for Turkey, although many later returned. Russia looked to ‘modernize’ Kars by laying the new orthogonal city grid and constructing buildings in its omni-present baroque-infused historicism style, much as elsewhere in the empire although here built with local black volcanic tuff. It also started ‘re-settling’ the territory, many ethnic Russians came or were sent here, including the dissenting Molokans and Dukhobors, as well as followers of the official Orthodox church and members of other ethnical and confessional groups including Armenians, Yazidi Kurds, Ukrainians, Estonians and Germans. Russian villages then appeared in the region. Most of the population of the city of Kars was Armenian.

After the outbreak of World War I, the Ottoman Empire sought to drive Russia away but failed losing the Sarikamis battle in 1914 with huge casualties and also losing further territories in the result. This was one of the triggers of the Armenian genocide in Turkey. Then after the two Russian revolutions in 1917, Bolshevik Russia signed the Brest-Litovsk treaty ending its participation in World War I and returning Kars and other occupied territories to Turkey. However, the Ottoman Empire was on the losing side of the war, signing the Mudros Armistice in 1918; the British-led Entente formed independent Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and Armenia receiving the disputed land. The short-lived Armenian Republic sought to consolidate more Turkish regions which had a largely Armenian population; that met with resistance from the nationalistic forces headed by Mustafa Kemal (later Ataturk); the Turkish Armenian war followed in 1920, and it was during this period that Armenia lost Kars. Meanwhile, Soviet Russia drove the British forces out of the Caucasus, installing communist governments in the newly founded republics; Soviet interests coincided with those of Kemal. Russia supported him with arms, ammunition, and money; then the power in the former Armenian Republic was taken by a revolutionary committee. Eventually the Soviets struck a deal with Kemal, ceding the Kars region, consolidating the power in the Caucasus and not caring much about the population that was left behind. Now it was time for Armenians and Russians to be driven away, often with catastrophic effect. Former Russian settlements were given Turkish names. Communities became extinct, replaced by the newly settled.

Anti-colonial in their proclaimed goals, the modernist powers that were Bolshevik Russia and Kemalist Turkey, played along the old colonial principles. Claims were put forward by Stalinist USSR after World War II regarding the Kars region, and Turkey joined NATO as a means of protection. After the breakup of the USSR and the 1st Karabakh war (1992–1994) that followed in its wake, many Jafari Shiite Azerbaijanis fled to Kars, forming a significant minority. Following that conflict, Turkey closed the border with Armenia. The largest population today of Kars is Kurdish; the oldest families in Kars are said to have moved there less than a hundred years ago. And the disputed crossroads city has become remote and provincial.

Walking the streets of Kars in 2009, Sher refined his melancholic vision and his interest in the mundane. In the book’s foreword, he wrote: “After my time spent photographing in Turkey, I saw Russia more clearly, as if in a mirror. Since then, I have grown only more convinced, the best remedy for orientalist arrogance is to look for similarities wherever you travel, rather than differences of the other.”

Curiously, an earlier book by Orhan Pamuk, ‘The White Castle’, published in 1985 is largely dedicated to the same idea: its protagonists, a Venetian Italian and an Ottoman Turk, swap identities with each other, which goes unnoticed by.

Ever since Kars, Max Sher has largely focussed on landscapes that are shaped as a result of complex economic and political developments. Arguably, his most exhibited body of work is ‘Palimpsests’ (2014–2015), published as a book in 2018 and shown as a solo exhibition ‘Commentary on the Landscape’ at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art (2021). The photographer travelled around Russia for seven years, taking pictures of urban structures that you see anywhere, like municipal offices, construction sites, train stations and residential blocks, with the goal of producing a set of wholly representative images. The result is beautifully unnerving.

And the title ‘Palimpsests’ can be extended as a larger metaphor for Sher’s oeuvre. ‘Infrastructures’, a joint project with Sergey Novikov (b. 1979), created between 2016 and 2019, include staged and documentary photography as well as fifty essays. It is a study of physical objects like roads, bridges or pipelines seen in the optics of political significance.

Having ventured so deeply into the territory of co-existence of image and text, Sher understandably names Allan Sekula (1951–2013) and David Goldblatt (1930-2018) as his forerunners. Both of these innovators often turned to text as a means of expression no less important as the visuals, being critics of late capitalism and colonialism, like Max Sher, even if he perhaps inhabits different ground. This interest is reflected in a pseudonym Sher used once when he photographed a former Soviet closed town for a German magazine: Bernd Goldblatt, a combination of Bernd Becher (1931–2007) David Goldblatt (1930–2018).

Over the years, Max Sher has become an important artist and documentary photographer in Russia. In 2019, he participated in the ‘New Landscape’, curated by Anastasia Tsaider (b. 1983) and Petr Antonov (b. 1977), a group exhibition shown at Yeltsin Center in Ekaterinburg, then later at the Ekaterina Foundation in Moscow, as well as other venues. Photographers included Tsaider and Antonov, Alexander Gronsky (b. 1980), Valery Nistratov (b. 1973), Sergey Novikov, Liza Faktor (b. 1975) as well as Max Sher. In some sense, the exhibition was the local analogue of the ‘New Topographics’, an important exhibition dedicated to the re-conceptualization of landscape, first displayed in Rochester, New York in 1975.

It was only much later in Berlin, where Max Sher has been living since 2021, that he revisited his 2009 ‘Snow’ project which had never actually been shown or published, adding to it new ethnographical and historical research. “My final book veered quite far … because the project sat in my archive for many years before I realised that I wanted to publish it as a book since Russian imperialism came back into the spotlight with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and threats to other neighbours. Detailed captions and essays in the book are a product of this new lens though it was not really difficult since history is there at every corner, almost literally.”

‘Snow’, which Max Sher started in 2009 is the earliest project which he turned into a book, and it is his own palimpsest, encircling the sixteen years of his photographic career.