Engelke, an Artist Who Fights Banality with an Axe

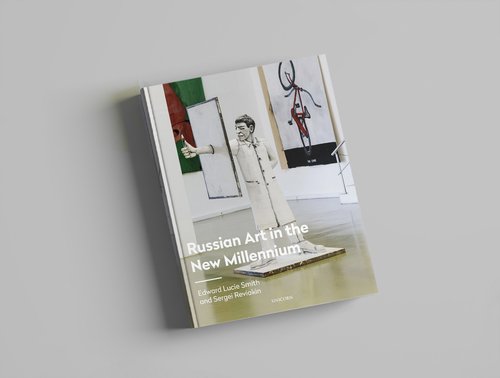

Nestor Engelke. Skulls. Exhibition view. St. Petersburg, 2025. Courtesy of Jessica Gallery

St. Petersburg artist Nestor Engelke has developed an axe-painting technique, using a carpenter's tool to create darkly ironic commentary on cultural icons of the past. However, his latest installation, ‘Skulls’, at the Jessica Gallery seems to speak more about the present.

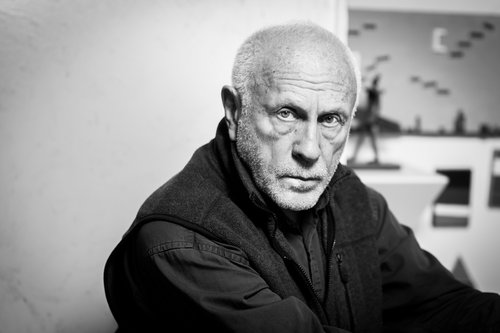

All artists rebel against their masters and predecessors at some point, but few take it as far as raising an axe at them. In fact, Nestor Engelke (b. 1983) is probably the only one. His signature technique of ‘axe-painting’ is a paradoxical combination of creation and destruction. His replicas of classical portraits, created on splintery raw wood with the faces cut out, are disturbing and haunting, yet immediately recognisable. Engelke’s work lies at the intersection of painting, sculpture, and performance art – he often swings his axe in front of cheering crowds at gallery openings. The performative aspect of his work is important to him, the artist tells me when we meet at his solo exhibition at the Jessica gallery in St. Petersburg. It turns out that performance was his first medium of choice. Born into a family of architects and trained as an architect at the Ilya Repin State Academy of Arts in St Petersburg, his career path seemed almost predetermined from birth. Yet he chose a different route. He joined the Sever-7 (North-7) art collective, led by Leonid Tskhe (b. 1983) and Alexander Tsikarishvili (b. 1983). He took part in its group exhibitions as a performance artist, inventing rituals that unite the human body (his own) and a tree into a single organism.

When I asked Engelke how he came up with the idea of ‘toporopis’ (axe-painting), he seemed at a loss to explain it, as if it had been ripening in his mind for years. When he was a child, his parents would take him to their dacha, where he was often asked to cut firewood. As a possible future architect, he learnt how to draw. The idea of combining ‘two unjoinable things – art and an axe’ came quite naturally to him. He is mesmerised by the texture of wood: ‘the visual side of it, all the cracks and notches’. For him, working with wood is akin to travelling back in time to a primal world where art as we know it did not yet exist – he likes to immerse himself in what he calls ‘proto-drawing, proto-painting and proto-sculpture’. Yet he takes his entire cultural background with him on that journey. In St. Petersburg, a city steeped in cultural treasures, the ghosts of deceased geniuses are hard to avoid, and every art professional lives in the shadow of the Hermitage from birth to death. The dark irony of deconstructing cultural icons with an axe is rooted in the city's myths and tropes, beginning with Dostoevsky’s character Raskolnikov: a rebellious young man who kills a rather repulsive old lady with an axe in a futile act of revolt against philistine morals, only to repent later.

In several projects, Engelke employs the same technique of brutal estrangement, forcefully stripping familiar images of their individual traits and the veneer of banality acquired over years and centuries. In his ‘portraits’, facial features are removed, leaving only a general outline of the figure. One of his first total installations was called ‘Pavilion for an Axe’s Reading’ (2020). This wooden structure, which evokes a shrine, featured ‘axe-painted’ portraits of Russian literary classics including Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov – a pantheon of writers whose names everyone knows, but whose books hardly anyone opens after leaving school. This iconoclastic gesture is both shocking and therapeutic; an attempt to mend a troubled love-hate relationship with the classics, which, according to Mark Twain, “everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read”. Coincidentally, after its premiere at the Ovcharenko Gallery in Moscow, the installation was displayed for a few months at the Gogol Centre, an avant-garde theatre named after Nikolai Gogol.

In ‘Art Gallery named after prof. Woodman’ (2023), the artist performed the same surgical operations on classical paintings, including Rembrandt’s ‘The Night Watch’ and 17th century Dutch portraits. The Hermitage has an exceptional collection of Golden Age Dutch paintings, whose pale faces and intricate white lace haunt any St. Petersburg artist from childhood as an unattainable ideal of painterly prowess. Re-creating these works with an axe on wood seems like a painful separation from the Old Masters, the spiritual ancestors of every artist. Engelke dreams of displaying these axe-portraits in major museums, alongside the originals. Is this an act of rebellion or humility? In any case, the project remains a dream, since contemporary art interventions are not welcome in Russia's major state museums nowadays, and transporting artworks from St Petersburg to European institutions does not seem feasible in the near future.

Engelke’s most recent project is on display at the Jessica Gallery in St. Petersburg until the middle of December and here there are also subtle connections with the Old Masters, particularly the philosophical still lifes that were so prevalent in Dutch and Flemish art. “It’s like a ‘vanitas’ painting, but you can walk around inside it,” the artist explains as though it is obvious. The piece was originally conceived as part of a larger installation called ‘The New Forestry Academy’, a collaboration with St Petersburg artist Fyodor Hiroshige (b. 1982). Scheduled to open last summer at the Na Solyanke municipal gallery in Moscow, the show was cancelled at the last minute by the gallery for unspecified technical reasons. The current exhibition is simply called ‘Skulls’. It is a total installation, occupying the entire space of a converted warehouse. The floor is covered with construction debris, and large wooden skull-shaped sculptures rise up above it.

This shape will be familiar to fans and collectors of Engelke’s work — the artist has produced quite a few smaller skull-shaped sculptures over the past few years. Yet the current project feels eerily topical to any visitor accustomed to seeing photographs of destroyed cities in the news. Over the past three years, these shocking images have become familiar, almost banal. However, as always happens at an Engelke exhibition, this veneer of triviality is shattered by the first swing of his axe. Suddenly, visitors become part of the ‘nature morte’ – it is worth noting that the French and Russian word for ‘still life’ literally translate as ‘dead nature’. You are invited to walk among the debris, where death looms overhead in all its raw, wooden materiality. It is the only thing that thrives and reigns over the ruins. If you dare, you can even contribute to it – Engelke holds regular skull-making workshops at the exhibition. And don't worry about bringing your own axe – these will be provided.