Elena Kovylina: A backwards retrospective

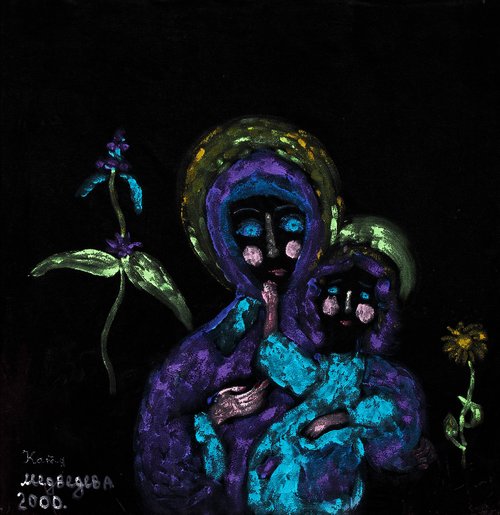

Elena Kovylina. Cryo-freezing, 2022. Oil on canvas. All-Russian Museum of Decorative Art

One of the most radical Russian female performance artists of the 2000s has unveiled a big exhibition of figurative paintings at the Museum of Decorative and Applied Art in Moscow. Impressed by this metamorphosis, art critic Sergey Guskov traces her convoluted artistic back path to its origins.

If you've never worn at in foil hat but would like to try one out in a suitable setting, then go to Moscow and visit the exhibition ‘Artifacts and Gadgets’ by Elena Kovylina at the Museum of Decorative Arts. There, they are literally offered to the visitors. In addition, a series of canvases juxtaposes folklore in the form of fairy-tale characters with modern technology, like all kinds of drones and communication tools. ‘We can only rely on vague sensations, on deja vu. We can loosen systemic boundaries a little bit, we can hint. That's all art can do. Art can't prove anything, it's not a science’, Elena Kovylina (b. 1972) says on video at the exhibition. The artist implies that humanity has gone back to where it once came from. However, to a great extent, this is evidenced by the unusual evolution of the artist herself.

Characteristically, at the anniversary exhibition which marks her 50th birthday, Kovylina's name is included in the very body of the title, rather than standing apart from a title made by her. Indeed, she is presented here as a naive artist not entirely aware of what she is creating, and the museum and curator Alina Saprykina shape her unruly creativity into a product which is easy to digest. This is all the more surprising, since Kovylina started out in the 1990s as a representative of an extreme radical wing in art.

Kovylina has often taken the opposite path to what most artists of her generation were doing. In the spring of 2018, for example, at the Danilovsky Market in Moscow, she unveiled a series of paintings, ‘Cultural Carrots’, in which she depicted fruits and vegetables and sold the mona stall. Later with this project, in which she replaced critical reflection with primitivist irony, the artist toured various venues in Moscow and other cities around Russia.

But the real turning point in Kovylina's work came a little earlier, in the mid2000s. A paradigmatic shift took place in the international art process at that time: politically engaged art, which used to resound at all kinds of biennales and was praised by art theory magazines, suddenly became redundant. Artists fascinated by mysticism, the paranormal, mythology, ‘alternative forms of understanding’ came to the fore. It turned out that the generation that grew up on the internet was paradoxically more prone to pre-rational thinking than the generations that preceded it, the generations growing up with the TV and newspapers.

Kovylina captured this global shift with perfect clarity. and has become one of the pioneers of the turn towards the supernatural in the domestic context. As part of the exhibition ‘Eternal Time’ at the Iragui Gallery in Moscow in 2015, the artist restarted the passage of time. In doing so, she drew on developments in the experimental laboratory Noosvyaz, which she invented in Krasnoyarsk, dealing in remote energy influences. ‘I am aesthetically framing the technology, trying to visually convey to the viewer that fantastic reality, which thanks to the discoveries of a group of daring crazy people becomes an existential possibility’, Kovylina told Colta.ru at the time.

If we go back in time, we can see a striking difference. In 2014, at the European Biennale Manifesta, whose tenth anniversary edition was held in St. Petersburg, she showed the project Equality (first held in 2007 in Paris). People came out onto Palace Square in front of Hermitage, stood in a line on stools of different heights, so that, according to the height of the participants, their eyes were all at the same level. This concise work about fundamental societal problems, ranging from inequality of opportunity to problems of forced equalisation, was well remembered by the audience at Manifesta.

Even earlier, in 2009, Kovylina held a performance entitled ‘Would you like a cup of coffee, or Burn the World of the Bourgeoisie?’ as an homage to Luis Buñuel's ‘The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie’, which she also repeated several times. She set fire to a tea-party table, sat at it herself, and even invited guests, usually art functionaries, patrons or collectors.

Another example of the artist's adventurous early practices was a boxing match, staged at the XL Gallery in 2005. All those present were invited into a real boxing ring, where Kovylina was waiting.The artist, who is professionally trained in this sport practically beat all of them - only the scandalous activist and artist Alexei Plutser-Sarno (b. 1962), outdid her, seriously injuring the performer herself. But Kovylina was prepared to play by the rules she had established, honestly and to the end.

If we go back to the artist's first experiments, the Waltz project of 2001 comes to mind. A student of Rebecca Horn's workshop at Berlin Art University at the time, dressed up in a military uniform with medals, Kovylina danced with randomly chosen partners and drank a shot of vodka after each dance. ‘Feminist art is socially engaged, it is always an action, an event,’ Kovylina wrote the year before in her ‘Red Stocking’ manifesto in the pages of the Moscow Art Journal.

It is a pity that this kind of retrospective is nowhere to be seen, it could tell a lot about the history of contemporary art in Russia and in the world.

Artifacts and Gadgets by Elena Kovylina

All - Russian Museum of Decorative Art

Moscow, Russia

September 13–November 10, 2022