Nikolay Polissky. Bamboo Waves, 2017. Northern Alps Art Festival, 2017

Russian on the Japanese contemporary art scene

Having joined forces with local curators, several Russian artists of different generations have won the hearts of Japan’s rural population, conservative by nature and wary of outsiders. From a newly opened Kabakov museum to a recent installation by young artist Ekaterina Muromtseva, in Japan, you can find Russian art where you least expect it.

There is a dark room in an old Buddhist monastery in the mountains of northern Japan, with figures moving across blue celluloid film projected onto the walls, like a procession of disembodied human souls. Around the prayer room in the monastery, painted in blue, are life-size watercolour images of local residents, each carrying their own personal burden. This is an installation by Ekaterina Muromtseva (b. 1990), which is at the centre of the NAAF 2021 Triennale (Northern Alps Art Festival, October 2 – November 21, 2021). It represents the latest piece in an expanding mosaic of Russian contemporary art across Japan. Although relations between Russia and Japan have often been tense on a political level, Russian culture has long been a powerful source of fascination and inspiration for the Japanese. Artist and teacher Varvara Bubnova (1886–1983), who brought the ideas of the Russian avant-garde with her to Tokyo in 1922, later passed them on to Yoko Ono, a relative by marriage. The Japanese Fluxus leader and partner of John Lennon always spoke of her gratitude to her Russian teacher for showing her the path of free creativity. Bubnova helped to spread the ideology of Russian modernism further to generations of students at Waseda University, where she taught until returning to the Soviet Union in 1958.

In more recent times, the presence of Russian art has grown with the arrival of Ilya (b. 1933) and Emilia (b. 1945) Kabakov in Japan. The pair first exhibited Ilya’s installation ‘Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album)’ in Nagano in 1991. Eight years later, they created an installation in the rice fields of Niigata, an agricultural region north of Tokyo. Multi-coloured silhouettes of peasants, frozen in an eternal harvest, line the rice paddies and open a path up into a forest filled with art-objects, installations and meditative spaces created by artists from around the world for the Echigo-Tsumari Triennale. Many of the works, such as Chris Matthews’ ‘Nakasato Scarecrow Garden’ and Oiwa Oscar’s ‘Scarecrow Project’ echo the simple, but complex, installation by this influential couple. ‘The Rice Field’ led to a perception in Japan that the Kabakovs were a manifestation of great Russian culture, on par with Leo Tolstoy, film director Sergei Eisenstein, composer Dmitri Shostakovich and animator Yuri Norstein. There is much behind the rice paddies and the rice harvest which inspired this stand-out installation at Echigo-Tsumari. Rice is a cult object in the inner Japan, so-called “Ura-Japan”, beyond the megalopolis. Japan has struggled for decades to find solutions to problems caused by its ageing and shrinking population, which are acute in such rural areas. For the trienniale’s mastermind, Fram Kitagawa, an art historian, curator and one-time leader of a communist student movement, contemporary art is a way of tilling the soil of these regions. Over several decades, Kitagawa has worked to create a network of art festivals across Japan, which seek to stimulate tourism, source funding and raise attention to lesser-known regions in Japan, as well as providing rich content for social media. They include the Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, Northern Alps Art Festival, Setouchi Art Fest, Okunoto Triennale and Ichihara Art Mix. These festivals have brought many of the international art world’s biggest names, such as James Turrell (b. 1943), Christian Boltanski (1944–2021) and Marina Abramović (b. 1946), to small Japanese towns otherwise off the map.

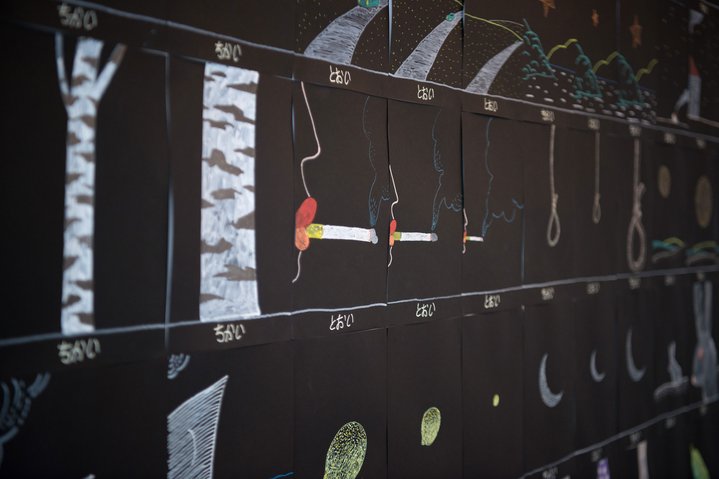

Such projects have required the blessing of conservative rural landowners initially suspicious of the value of contemporary art. With time, they have won over much of the local population. This is thanks in large part to Kitagawa’s grassroots integration of art into the landscape, his cultivation of a mutual respect between visiting artists and local residents and, perhaps, a lack of colonial rhetoric. As he describes in his book ‘Art Place Japan, the Kabakovs’ installation played a key role in this process. In fact, by popular demand, the Kabakovs were invited back to Niigata in 2015 to create another installation above the rice field called ‘The Arch of Life’. Then, in July of 2021, a museum dedicated to their work (‘Dreams of the Kabakovs’) opened in nearby Nohbutai. This November, they plan to open another installation called ‘The Monument of Tolerance’. The inclusion of Russian artists in these festivals owes much to Wakana Kono, a curator and professor at Waseda University. Kono, who holds degrees from both Moscow’s Russian State Humanitarian University (RGGU) and Tokyo University, is a specialist in Russian Silver Age literature by training, but her true love is for contemporary Russian art. Over the past twenty years, she has helped to bring many Russian artists to Japanese audiences, including Alexander Ponomarev (b. 1957), Vladimir Nasedkin (b. 1954), Tatiana Badanina (b. 1955), Alexander Konstantinov (1953–2019), Leonid Tishkov (b. 1953) and Nikita Alexeev (1953–2021). Their installations somehow become organic elements of a landscape worthy of Miyazaki’s watercolours. In more recent years, a new generation of Russian artists have also entered the orbit of the Japanese triennales, including Taus Makhacheva (b. 1983) and Muromtseva. Perhaps the most natural Japanese fit among Russian contemporary artists is Nikolay Polissky (b. 1957), co-founder of the Kalugan land art festival Archstoyanie. His fundamental idea echoes that of Kitagawa: rural revitalization, or, to put it simply, inspiring local populations to quit drinking and start working. Polissky used his own experience at the Northern Alps Art Festival in Omachi, a small town in Nagano, a region known both for agriculture as well as skiing and hydro-electric energy. With its shrinking local population, locals in Omachi initially were sceptical and in 2016, some 2,160 people signed a petition against it. But the 50,000 tourists who visited in 2017 lifted the region’s economic fortunes and morale.

As he did at Nikola-Lenivets, Polissky brought locals together to create megalomaniacal structures with their own hands using natural materials. His efforts led some Omachi farmers to form the ‘Ichie-kai’ (‘First art’) group and they affectionately nicknamed their imported leader Niko-chan, which means “Smile-chan” in Japanese. The ‘Ichie-kai’ group has since gone on to work with other artists, too. For the 2021 edition of the festival, they partnered with a Taiwanese artist for another ambitious installation: over the course of 11 days, they planted in the local rice fields 400,000 bamboo chopsticks made at a factory in Taiwan. The choice of Russian artists invited to Japan hints at several principles guiding the Japanese festival projects. Here, one does not find politicized work, but instead poetic and interactive installations that fit into an already familiar context for Japanese viewers. Both Polissky and Muromtseva are clearly in dialogue with the Kabakovs’ ‘Rice Field’, exploring similar motifs around the aestheticization of labour. The proverbial russkoye bednoye - Russian brew of arte povera - finds its reflection in Japan’s wabi-sabi. In the case of Muromtseva, the curators were intrigued by her dialogue with the local population. Her use of the deep blue-green color hints at indigo, that unofficial symbol of Japan’s rural, hand-made culture. Somewhere in that blue sublime, Japan and Russia meet.