Bright Triumphs over Black & White

Natasha Arendt. Landing of the Cloud, 2022. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

Russian-British artist Natasha Arendt has turned to geometric abstractions, seeking refuge from dark times in vibrant colours. The show in London celebrates a new direction in the art of this distant relative of celebrated marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky.

B&W and Bright showcases new paintings by London-based, Russian-British artist Natasha Arendt. Running in parallel with an exhibition of work by Katya Gerasimova Bosky, a native of St.Petersburg, at the recently refurbished St Marylebone Art Space, formerly Samworth Hall. The opening night was well attended, there were the art collectors Maxim Bokser and Irina Stolyarova, owner of the Russian Art + Culture media platform Natasha Butterwick, curator Sasha Burkhanova-Khabadze, artist Carolinda Tolstoy and Andrew Logan’s representatives among others.

Natasha Arendt comes from an artistic and medical dynasty. One of her forefathers, military surgeon Nikolay Feodorovich Arendt, treated both Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov. Natasha grew up in Moscow in a legendary bohemian enclave in Upper Maslovka where she encountered Soviet art heros such as Yuri Pimenov (1903–1977), Sergei Luchishkin (1902–1989), Alexander Labas (1903–1983), and sculptor Ernest Neizvestny (1925–2016). Her first art teacher was her grandmother, sculptor Ariadna Arendt (1906–1997), who in late 1920s was a student of sculptor Vera Mukhina (1889–1953) and artist Vladimir Favorsky (1886-1964). Natasha’s own artistic career began in the studios of Ariadna Arendt and her second husband Anatoly Grigoriev (1903–1986), who was also a sculptor.

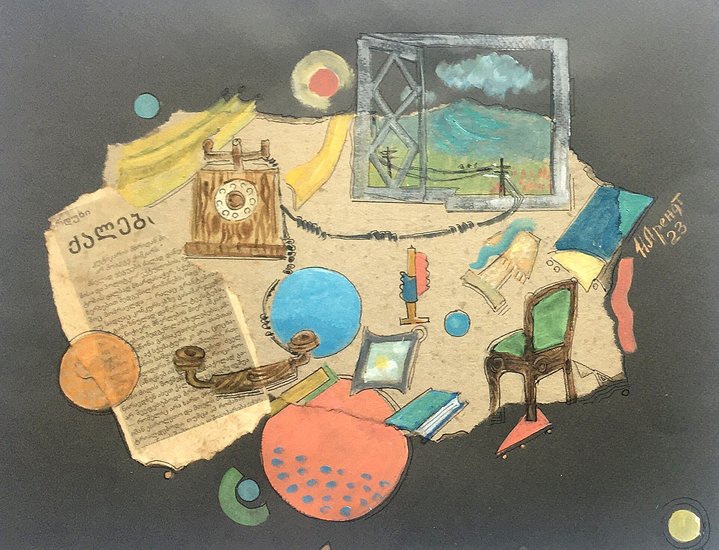

Natasha studied stage design at an art school of the Moscow Art Theatre (MKHT) and later joined the Moscow Union of Artists. She follows the tradition of neoprimitivism examining Soviet and post-Soviet Russian culture, its visual language, artistic techniques, symbols, and clichés. Her idiosyncratic still lifes in muted colours of fruit, fish or kitchen utensils against rough, dark backgrounds are instantly recognisable. She has exhibited both within Russia and abroad, including Ca'Foscari Institute in Venice, the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the Russian Museum in St Petersburg, the Moscow Museum of Architecture, the Maximilian Voloshin Museum in Koktebel (Ariadna Arendt and poet Maximilian Voloshin were long-life friends).

Arendt’s recent works, a mix of figurative and abstract works, are shaped by the current political situation, made over the past year and dwell on the tumultuous and tragic events, both political and personal. Yet, her art carries hope and optimism, she chooses to celebrate life rather than get stuck on grief and loss. There is gentle humour, gratitude, even awe.

“As the recent events unravelled, I experienced a feeling of panic. Probably, this new series is the result of a pendulum effect: the darker the reality, the stronger is the longing for light and colour.”, reflects the artist. “I changed my palette to bright, vivid colours; I switched from oil paints to acrylics and gouache. I spontaneously followed my inspiration which counterbalanced the awful reality and sustained me throughout the darkest months. I wanted to focus on the light and colour, rather than sink into despondency and darkness. Our family heritage gave me emotional support so more than half of my recent works which I am showing here at Marylebone illustrate the happiest episodes from our newly published collection of family memoirs, Aivazovsky and His Descendants. Revolution – Before and After. There is plenty of tragedy in these recollections, but I chose to focus on the moments of beauty and joy instead.”

These recent paintings read like a palimpsest of thoughts and emotions: some of the abstractions have a Miroesque quality, others echo the past experiments of Suprematism of early 1920s. WeatherReport, shortlisted for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 2022, or Between Past and Future (2022) are evocative of El Lissitsky’s (1890–1941) Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge . Natasha’s grandmother Ariadna Arendt and her grandfathers Meer Eisenshtadt (1895–1961) and Anatoly Grigoriev, all studied at VKHUTEMAS, so such allusions are unsurprising. There are glimpses of Magritte (1898–1967), an artist much admired by intellectuals of the late Soviet era. “All this surrealism in my work is a response to the bizarre, surreal irrationality of our present life,” says Arendt.

It is nostalgia for her family’s history and serene pre-Revolutionary days spent in the family nest in Boran-Eli which bring out beautiful, transparent colours in her works. Most paintings are accompanied by quotes from the book, Aivazovsky and His Descendants. The painting, Entrance to the Boran-Eli Estate is displayed alongside the reminiscences of Natasha’s grandmother, Ariadna Arendt: “From the earliest childhood I spent my summers in Boran-Eli near Stariy Krim, the residence of my aunt Ariadne Nikolaevna Latri. Her husband Mikhail Pilapidovich Latri, the grandson of I.K. Ayvazovskiy was himself an artist. In the summer Boran-Elyi was the gathering place of creative intelligentsia – K.F. Bogaevskiy, A.V. Lentulov, M.A. Voloshin, V.P. Belkin, M. Tsvetaeva and many others”.

Trio for Two addresses the memories of Mikhail Lattry’s (1875–1942) niece Gayane Mickeladze, a British actress of Russian, Armenian and Georgian origin, and a great granddaughter of Aivazovsky: “My parents always seemed to become the centre of attention when mother's family congregated and music was played...Uncle Misha (Lattry) played the mandolin, cousin Kolya (Lampsi) – the guitar, and cousin Alexis (Hanzen) played the violin and whistled beautifully at the same time... He and my mother sounded together like a Trio.”

Her art also is a nod to the Russian Silver Age, and especially the legacy of Mikhail Lattry and the artist/pilot Konstantin Artseulov (1891–1980) both distant relatives of Arendt. Artseulov, who introduced spin into the repertoire of aerobatic figures and designed new gliders, wrote that “vocations of artist and pilot are so similar, requiring the same skillset, inborn or acquired qualities and characteristics: spatial awareness, sensitivity to movement, tempo and rhythm, subtle sense of colour, observation and analytical skills, romanticism and entrepreneurship, emotional depth and profound knowledge of one’s craft.” Mikhail Lattry’s sketch for his monumental mural at Le Bourget airport seems to echo this idea, and in turn inspiration behind Arendt’s Landing of an Aeroplane, which celebrates both Lattry, an early exponent of Art Deco, and Artseulov.

On the whole, Aivazovsky and His Descendants offers a key to understanding the exhibition. This book which first launched in Russian in January and is due out in English in April, is an invaluable collection of memoirs written by Aivazovsky’s descendants including Alexander Aivazovsky, Gayane Mickeladze and Ariadna Arendt. It also contains rare unpublished photos from the archives of the Arendt family and from the estate of Dr Henry Sandford whose mother, Olga Mickeladze, was a great granddaughter of Aivazovsky. The volume also includes a genealogical tree of the Aivazovskiy family.

Having escaped the Revolution, Alexander Aivazovsky insisted that members of the extended Aivazovsky clan put their family stories to paper: “If each of us described everything kept in our memory, such memoirs would have evoked the most accurate visions of the past.” It seems that Natasha Arendt follows this advice by offering a precious glimpse into the workings of memory and creative imagination by letting us share in the hidden treasures of her family’s artistic past.

B&W and Bright: an exhibition by Katya Gerasimova Bosky and Natasha Arendt

London, UK

30 March – 26 April, 2023