High visibility stakes

Dmitry Gutov. Artist in his studio. Fragment. 2010. Metal, welding. 201x163x40 cm. Private collection

Big museum exhibitions and international biennales give Russian artists global exposure, but does that affect the market for their works?

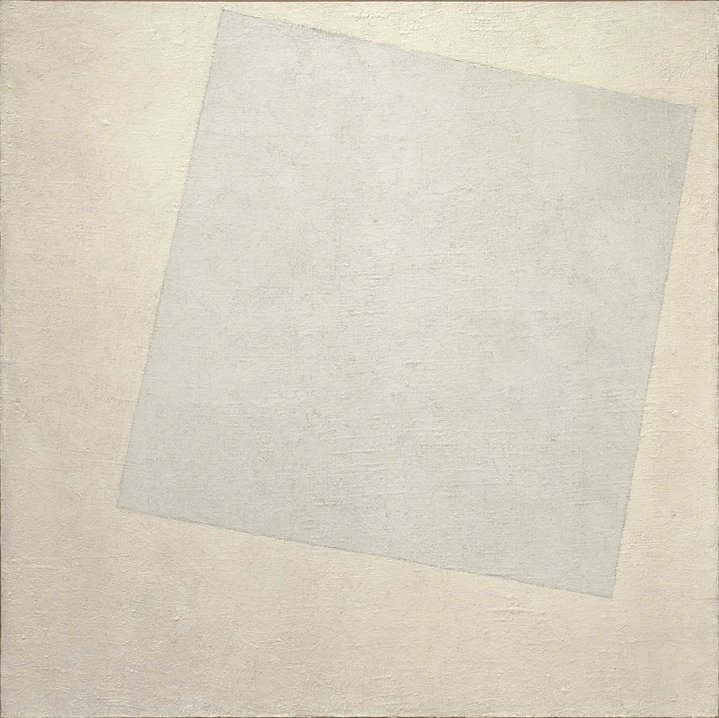

The growth of the Russian art market, historically centred in London, has coincided with an unprecedented period of globalisation in the arts, where several big museums in the West are acquiring works by contemporary Russian artists. London has hosted no less than six major exhibitions of Russian artists at top museums over the past decade. How has this unprecedented interest abroad influenced the market value for Russian Modern and Contemporary art? A solo retrospective at a major museum is the most effective way to raise the visibility of an artist by retelling his or her story to a wider audience. Tate Modern alone has staged three such comprehensive shows for Russian artists over the past decade: Kazimir Malevich in 2014, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov in 2017 and Natalia Goncharova in 2019. The Malevich (1879–1935) retrospective was the first in over a quarter of a century and was long overdue. It was followed by exhibitions around the world in honour of the 100th anniversary of his 1915 ‘Black Square’. Malevich was not a prolific painter and the majority of his works are in museum collections, so it is impossible to rely on analysis of market data to quantify the effect of this exposure, but there are simple facts that point to a boost in his market value as a direct result.

Seven of the top 10 auction prices for Malevich were set immediately following the 2014 Tate retrospective thanks to the re-sale of his 1916 his ‘Suprematist Composition’. After initially being sold at Sotheby’s in 2008 for USD 60 million, 10 years later it fetched a staggering USD 85.8 million. Finally, two of his other Suprematist paintings sold at Sotheby’s in 2015, having failed to find buyers when first offered on the private art market a decade earlier. A critical mass of data is necessary to calculate market performance. This can be harder if an artist’s works are rare. In the case of Ilya Kabakov (b.1933), there are more works on paper traded on the art market than oils. Thus, it makes sense to analyse the prices he fetched in the years before and after the Tate show. The results clearly establish that prices rose in the two years prior to the retrospective, with the strongest sale volume in 2018. It is still too early to assess the effect on market prices for Natalia Goncharova (1881—1962), since her exhibition only took place last year. Scarcely any of her major oils have appeared on the market over the past few years. Compare this with the records established by her works a decade ago, when her Rayonnist masterpiece ‘Les Fleurs’ sold for USD 10.9 million and established her as the most expensive female artist in the world at the time. Analysis of her works on paper at the main London auction houses over the past five years surprisingly show not a market boost, but tapering sales values in both 2018 and 2019. It tends to be contemporary, rather than modern artists, who benefit most from museum exposure. However, with the exception of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, there have been no retrospectives of living Russian artists at major Western Museums in New York or London. Although, far less effective than a solo museum show in raising visibility, how has representation at the Venice Biennale and Documenta influenced the market value of Russian contemporary artists?

In 2007, four Russian artists were selected to take part in ‘Documenta 12’, which in itself was a breakthrough. A whole generation passed with no Russian participation since Ilya Kabakov exhibited his legendary installation ‘The Toilet at Kassel’ in 1992. The four were were Anatoly Osmolovsky (b.1969), Dmitry Gutov (b.1960), Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949) and the video artist Kirill Preobrazhensky (b.1970). All were well established at home, but had barely any visibility in the West prior to their appearance at Documenta. The effect on their market in the West was negligible. Between 2006 and 2009, there were only four works by Dmitry Gutov offered at auctions in London. All failed to find a buyer. So far there is no auction market for Monastyrski. As for Osmolovsky, the majority of his works offered at auction have been sold at Vladey in Moscow, while the sales of his art in the West were not sustained. Since then, there has only been one more living Russian artist taking part in Doсumenta, Alexandra Sukhareva (b. 1983), who has so far not left an imprint at auctions in the West, although Tate Modern did acquire one of her works in 2017. The Venice Biennale tells a similar story: Since 2011, Andrei Monastyrski, Vadim Zakharov (b.1959) and Irina Nakhova (b.1955) have alone been represented at the Russian pavilion, giving them huge visibility in the centre of the contemporary art world. Zakharov is the only artist who has a consistent presence on the West’s art market, but through Russian art auctions, rather than international contemporary art sales. Tate Modern has acquired works by all three artists since their Venice appearance, but this has not yet translated into increased market exposure in the West. Zakharov’s prices are the same today as they were a decade ago and, like Monastyrski, Nakhova is not sold on the international auction market. Representation at two of the most high-profile contemporary art platforms in Western Europe, attended by the international community of art collectors should surely create market momentum there, so what has gone wrong? The economic crisis hit the art market in 2008 and in the middle years of the second decade of the 21st century the Russian art market was depressed. It was not a time for an artist little known in the West to try and enter it. For museums, however, this was the ideal time to make acquisitions.

As this situation seems to apply to the majority of artists, is there not perhaps a wider backdrop to this lack of market uptake of some of Russia’s greatest artistic talent? Among the major museums in New York, London and Paris, three centres of the art market with high number of collectors, the vast majority of Russian themed exhibitions over the past three decades have been about the Russian Avant-Garde. In the wake of Perestroika, there were four retrospective solo exhibitions by Russian Avant-Gardists at MoMA in New York during the 1990s.

More recently, the centenary of the Russian revolution in 2017 set off a flurry of international exhibitions re-telling the story and this of course boosted the market for the modern artists associated with that movement. However, it seems that despite the huge cultural shifts at the end of the Cold War, the exhibition agenda of Western museums has not changed even if their acquisitions policies have.

There has been no thorough survey of Russian contemporary art at any top museum in the West. The Pompidou comes closest with its Kollektsia! exhibition of 2017, however, despite its Napoleonic ambitions, this was a show to mark a generous donation of art, which had been assembled in a relatively short space of time. This leaves more than half a century of artistic life invisible to all, but a few dedicated followers: it is an untold story. The dampening effect that this has on the market for Russian contemporary artists may not be quantifiable, but it can be keenly felt.