Anatoly Osmolovsky Chairing the Discussion

Anatoly Osmolovsky. 'The score for the chair' performance at SlovoNovo. Lustica Bay, Montenegro, 2023. Photo by Marina Ohrimovskaya. Courtesy of SlovoNovo

This celebrated enfant terrible of Moscow Actionism has made a new performance at the SlovoNovo forum in Montenegro.

There is a simple chair standing on the stage, but all is not what it seems. In the space of an hour, it will be transformed into an art object by artist, critic and art historian Anatoly Osmolovsky (b.1969) who reveals to the audience the mechanisms by which cultural value is generated through an experimental performance conducted on what is otherwise an ordinary object. Osmolovsky starts by subjecting the chair to an array of permutations ranging from the formal to the farcical. First, he contextualises the chair by giving a brief overview of chairs in modern and contemporary art, a rather canonical trajectory of Duchamp, Beuys and Kosuth - re-enacting the latter he prints out a photograph and a Wikipedia definition, attaching them to the object. Next, he attempts to increase the chair’s cultural net worth by inviting Vitaly Mansky, a famous film director, to sit on it. A witch then conducts some weird magic ritual over the chair to give it longevity (the initial plan had been for a priest to sanctify it, but they all declined!); a model then poses with it, imbuing it with a touch of her beauty. Then one of the legs of the chair is sawn off and drilled into the middle of the seat, thus stripping it of its functionality. Referencing Christo and Jean-Claude’s wrapping of the Reichstag, and evoking the tragic times we live in, Osmolovsky’s assistants put the chair in a body bag which they then puncture with the protruding leg, a metaphorical finger up voicing ‘fuck war’. Then follow two final acts: a critical appraisal of the chair by art historian Petar Ćuković; and gallerist Marat Guelman (who was declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) valued the final result at 15,000 Euros.

We are at SlovoNovo, running in Montenegro for the 8th time, billed as the forum of free culture uniting many leading Russian thinkers and creators under a rather exclusive roof where tickets can cost 750 Euros. That participants grossly outnumber ticket-buyers makes it the perfect opportunity for mingling and creative exchange among Russian emigrés.

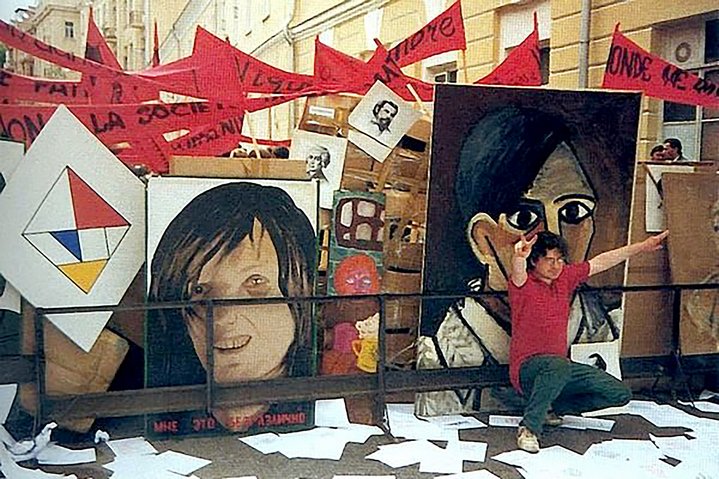

I had assumed the Osmolovsky I was going to meet would spit in the face of such a Salon, but it seems that times have changed for this one-time rebel. Osmolovsky was the most radical actionist artist of the 1990s, best known for his performance, ‘Dick on Red Square’ - known in academic literature as ‘Text’ by E.T.I, 1991. It was an infamous event where the artist and his collaborators lay down on Red Square in front of Lenin’s Mausoleum to spell the Russian word khuy (Dick) with their bodies.

Initially an engineer by training, Osmolovsky began his personal artistic journey through the discovery of Russian futurist poetry, Russian formalist art and then western 20th century art. He managed to avoid being drafted into the army through a stint at a psychiatric clinic and his connections in the world of rock music. As perestroika dawned, he joined the flow of liberated creatives and underground youth, making new connections amid poetic and artistic circles. His first attempt at performance is seen as the closure of the French film festival ‘Explosion of the New Wave’ which he organised with a group of friends who decided to recreate the final scene of Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Métro. They unleashed a bear in the public and staged a cake fight after the end of the film. The public mood was of fearless excitement, he recalls today. But as the country began to split and crack at the seams, you could not depend on institutions or edifices, and the artists took to the streets.

The actionist movement which developed in Moscow in the 1990s was a bold alternative to the cerebral intellectualism of Moscow conceptualism, figures such as Kabakov (1933—2023) and Andrey Monastyrsky (b. 1949) who had by then become the Gods of the underground art scene, with its apartment gatherings and trips out of town. Instead, a new generation took to the streets of central Moscow. In 1993 Osmolovsky scaled the Mayakovsky monument, hoisted by a forklift, and sat on the poet’s shoulder smoking a cigarette, the same year he and a group of collaborators stood with their pants pulled down in front of the White House.

Following the action in Red Square the artist had a five-year sentence hanging over him which never materialised because the country that ordered it ceased to exist. “I was one of the last people to deal with the KGB,” says the artist now, “after that the KGB as an organisation ceased to exist.”. Today, some thirty years later, its ideals are even stronger, with sentences exceeding those of the latter-day Soviet Union. Osmolovsky had to cancel an upcoming retrospective at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, “I don’t think my works can be shown in Moscow at all at this time”. It is a situation which feels out of control, he adds, “the insanity of those in power right now is very impressive, let’s put it that way.”

And yet he remains in Russia, his current mission is to provide alternative contemporary art education for young artists. Osmolovsky’s own art institute Baza has just entered its twelfth academic year. Artist Alisa Yoffe (b. 1987), one his best known protégés, sees Baza as a kind of actionist artwork in itself, “he wants to foster people who have an alternative mindset. He’s continuing his actionist activities, but as the director of Baza.”. The institution is completely independent with no external funding, and students study 20th and 21st century art, and get support in how to integrate themselves in Moscow’s artistic life. I ask Osmolovsky what he sees as the future of contemporary art education. “Contemporary art is a kind of lingua franca, which is a double-edged sword, on the one hand it can unite people, on the other hand it might become banal.” He regrets that the Moscow art scene has been what he sees as largely destroyed over the past few years but sees a new wave of non-profit self-organised artist spaces being created by artists who do not want to be associated with governmental institutions, oligarchs or galleries.

A tinge of nostalgia for his past bravado may cloud this current sobriety, but what are the options for a retired actionist? Reflecting on the fate of his contemporaries Oleg Kulik (b. 1961), Alexander Brener (b. 1957) and Avdei Ter-Oganyan (b. 1961), they have all moved away from the radicalism of their youth. In his educational work, Osmolovsky’s contribution is invaluable to keep the fragile flame of contemporary art practices in Moscow alive, a vibrant art scene which is becoming increasingly censored and repressed.