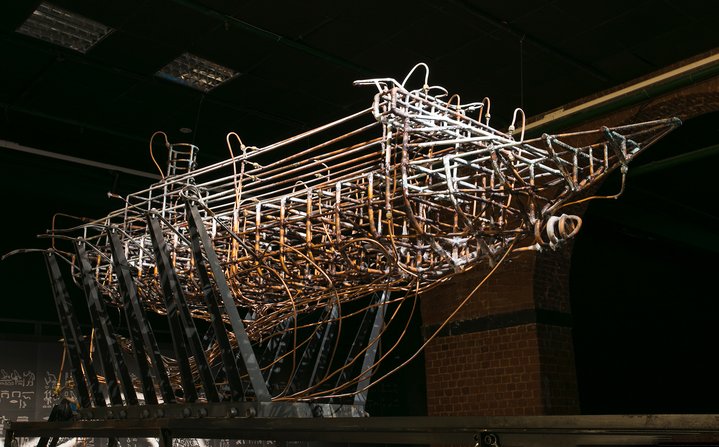

Alexander Ponomarev. Icarus, 2022. Courtesy of the Museum of Moscow

Alexander Ponomarev: On the waves of the free elements

Russian artist Alexander Ponomarev's exhibition 'Without Shores' at the Museum of Moscow is a fascinating journey across sea and desert.

This year Alexander Ponomarev celebrates his 65th birthday which is the impetus behind ‘Without Shores’, an exhibition at the Museum of Moscow where on show are works drawn from different years of the artist’s career. “I talk in a kind of artistic way”, Ponomarev warns me while guiding me through the exhibition space. He sees the show as a preparatory retrospective for a bigger one which is due to take place next year at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, where works by Alexey Bogoliubov, Russia’s great 19th century marine artist, will be shown on one floor and his on another. So Russia’s leading state museum of national art will simultaneously exhibit paintings by this Russian classic marine painter and this living artist whose life is inextricably linked with the sea. If Ponomarev had not been forced to retire from maritime service for health reasons, contemporary Russian art would likely have missed out from a great talent.

Ponomarev has made a powerful new work for the exhibition at the Museum of Moscow. ‘Icarus’ is an elaborate mechanical construction with huge wings which flap in the museum courtyard, although it can't take off. It has an aesthetic beauty, a central cylinder has gears which spin around, and as spectators come close, the wings begin to undulate like waves. “It is a very complex construction, the body is a collector, like the ones you find underground in sewers, it looks rather brutal and rough, however the mechanism is extremely complex, the gears move around like planets, each in its own orbit.” Ponomarev speaks with passion and at great length about the construction and how long it took to forge all the parts, something only those with an degree in engineering can fully understand.

You can see sketches for ‘Icarus’ in the museum's main exhibition space. The room is vast and accommodates installations, screens with videos of performances done over many years and numerous sketches of works that often look like finished pieces. Ponomarev starts out by painting his performances and installations, but he also writes poems about them. “I discovered that it is easier to capture the essence of what I've made in poetry.”

Standing in front of the installation, “Get Back On Board!” Ponomarev reads the poem ‘Get the fuck on board!’, which tells the story of the sinking of the passenger liner Costa Concordia which Captain Francesco Schettino abandoned with many passengers still onboard. At the time, a coastguard shouted these words to the cowardly seaman, and these form the title of the installation. Ironically, Ponomarev's work about this maritime disaster was shown in the Agafay Desert, during the 2014 Moroccan Biennale. The video of him on top of a sand dune presenting a ship woven out of reeds to the visiting public looks like the recording of a captivating performance. Ponomarev started to work on this piece after undergoing major surgery: “It was very important for me, it was my rebirth, my return to life.”

For three decades, the artist has been developing ideas around shipwrecks: “I have always talked about shipwrecks, ever since I started painting on fragments of wrecked vessels in 1991. It's a conversation about the dangers inherent in life because when a ship is covered with ice, it's very dangerous, it alters its stability and it could capsize. Just like our whole world, which is also sinking”. The frostbitten ship is another installation, Concordia, which depicts a schooner slowly turning into ice and then thawing out. Ponomarev first showed it at the 2014 Venice Biennale, in what he called the Antarctica pavilion.

Another installation is ‘String Theory’, which shows a ship suspended upside down on a net of guitar strings. “Over the last few years I've been involved in a free aesthetic of the natural elements. This means art which interacts with the four elements. The three already known, plus our human creative element. I can fly, float, or just think, the ocean where I am swimming is like the ocean in a Tarkovsky film. String theory is a theory of everything, it gives an understanding of the process of movement, an understanding of life itself, of its waves."

Ponomarev sets out string theory in a long and no fuss manner, referring to philosophers from Plato to his friend Alexander Sekatsky, and then leads me to a 12-metre long ceramic panel called Ouroboros, which depicts the sign of infinity in the form of a snake biting its tail against Egyptian hieroglyphics. It is a replica of part of the installation at Giza. There an enormous sandglass which rotates against the background of the famous pyramids, sand trickles down from it, forming another pyramid, “the pyramid of life”, as Alexander Ponomarev, artist, traveller, poet and philosopher says.