White Carte Blanche for Contemporary Art in Warsaw

Museum of Modern Art Warsaw. Photo by Maja Wirkus. Image from Museum of Modern Art Warsaw’s social media page

Warsaw's long awaited new Museum of Modern Art designed by American architect Thomas Phifer, has finally opened. A new monumental space in the heart of Eastern Europe which promises to show work which reflects our difficult times, and evokes a variety of emotions, much like the building itself, which has divided local communities.

Back in the mists of time in March of 2005, the Warsaw Museum of Contemporary Art was official born on paper at least, when the Polish Minister of Culture and the Mayor of Warsaw signed an agreement for the construction of a new museum on Parade Square at the foot of the Palace of Culture and Science.

There is a sense that the centre of Warsaw has long existed under a curse. It was completely destroyed during World War II then in 1955 the monumental Stalinist high-rise Palace of Culture and Science was built, a gift forced upon the freedom loving Poles by the ‘brotherly Soviet people’. Long an irritation for locals in the centre of the city, after the fall of communism and the coming to power of Polish Solidarity, this building found itself on the brink of being demolished. However, the Palace of Culture and Science had over the years also managed to become a symbol of Warsaw, and the authorities decided to save it and instead surround it on all sides with new skyscrapers. The plan only partly succeeded; the palace still dominates over its architectural surroundings. Parade Square, a large empty space was used during the Polish People’s Republic for marches, rallies and other mass events, but in the 1990s, demonstrators were replaced by street vendors and car owners who turned the square into a giant car park

On the other side of Marszalkowska Street, which runs parallel to Parade Square and the Palace of Culture and Science, are the 1970s modernist buildings of Warsaw's Centre Gallery and several residential, relatively elegant high-rise buildings. The building of the Museum of Contemporary Art was intended to be a kind of ‘counterpoint’ to the Palace of Culture and Science, without conflicting with Warsaw's modernism on Marszalkowska.

Many lances were broken over the museum’s design, and the competition for the best building design was held not once but three times, eventually won by New York architect Thomas Phifer. He proposed to build a white horizontal parallelepiped to house the museum and a black cubic theatre building next to it (the construction of the latter has been postponed).

The new museum building is simple, austere and minimalist. It has seven floors, five above ground and two underground and it occupies almost twenty thousand square metres. It has been constructed out of noble architectural concrete, and its completely white colour lets it stand out against the grey buildings of the centre of Warsaw. For architect Thomas Phifer white is the colour of optimism and concrete as a material is a symbol of the building's longevity. This is the first building in Poland and the largest in Europe with a suspended concrete façade, which integrates the museum into the surrounding space, making it part of the urban puzzle, complementing the city centre rather than dominating it. Thanks to its white colour, the museum building is clearly visible from different angles and grabs attention.

Speaking at the museum's opening, Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski noted that Phifer’s building “correlates perfectly with the houses standing on the other side of Marszalkowska Street. And in a way it polemises with the Palace of Culture and Science”.

Phifer's biggest challenge was working with the surrounding architecture, his building matches the Palace of Culture and Science in massiveness but does not compete with it in terms of scale, and at the same time, thanks to its simple geometric form, enters into a dialogue with Warsaw modernism. It would not make sense to compete with the silhouette of the Palace of Culture, a building too expressive to be overshadowed.

Not all the locals share the optimism of the mayor and museum staff and it has driven a wedge through the community. Conservative-minded Warsaw citizens refer to the new museum building as a ‘shoebox,’ or ‘white brick,’ and an ‘architectural nightmare.’ ‘Was it worth the 640 million zlotys spent on it?’ – they ask frothily. Some believe Poland is not ready for such contemporary architecture, that the museum building does not reflect anything uniquely Polish nor does it express the messianic idea that with the help of art it is possible to bring about great changes in the lives of Poles.

The interior of the building is dominated by an extraordinarily beautiful, dynamic staircase with a double flight of stairs which connects all the galleries, designed in the spirit of constructivism, in contrast to the restrained interior. On the opening day, it was the backdrop of a performance by established Hungarian contemporary artist Katalin Ladik (b. 1942) called ‘White Descent’ referring to the famous surrealist painting ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Through sound, this performance demonstrated the acoustic properties of the museum space and the scope of artistic possibilities that can greatly expand it. As I climbed this amazing staircase, the space brightened up gradually, with the two upper galleries lit by natural light flooding in from the skylights on the roof.

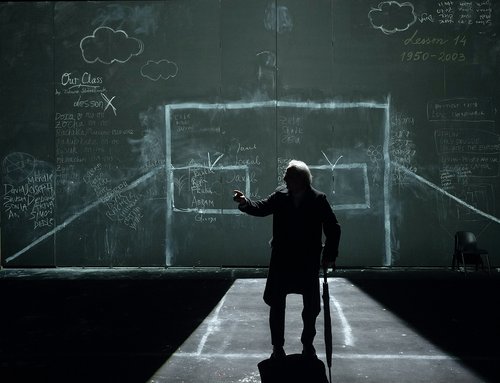

Currently showing on the ground floor is an exhibition ‘Warsaw under Construction. The Museum between the Square and the Palace’ which will run until January 2025 and it enables visitors to immerse themselves in the history of the construction of the museum and the complex if not dramatic successive transformation of Parade Square and the centre of Warsaw. There is a film about the protests of street vendors and their clashes with the police as in the 2000s Parade Square was filled with kiosks and stalls and when construction work started for the museum there were numerous clashes with the police which grew into riots. Next to this historical display there is an untitled work by Roma artist Selma Selman (b. 1991): a huge satellite dish inscribed in black paint, the words reading, ‘Lord, make me even more famous so I can escape from here.’ For Selman, this slogan describes her own history of overcoming the barriers of class and the patriarchy.

The museum’s first, temporary art exhibition which ran for a few weeks from opening day, consisted of nine large-scale sculptures and installations by female Polish and international artists from the permanent collection dedicated to the theme of fighting the patriarchy and other prejudices. “The white spots of art history need to be painted with coloured paint” as director of the museum Joanna Mytkowska put it. This exhibition included, among others, works by classic Polish artist Alina Szaposznikow (1926–1973), contemporary Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova (b. 1981), and a current favourite of the curators of international biennials, Chilean feminist icon Cecilia Vicuña (b. 1948).

After long and arduous political and architectural battles, contemporary art in Warsaw is finally finding its voice again, and artists are encountering a new place where they can speak in that voice. This museum has already been dubbed a ‘white carte blanche’ for contemporary art. It speaks to visitors in different languages, all you need to do is listen to it!