Where is the Body Hidden?

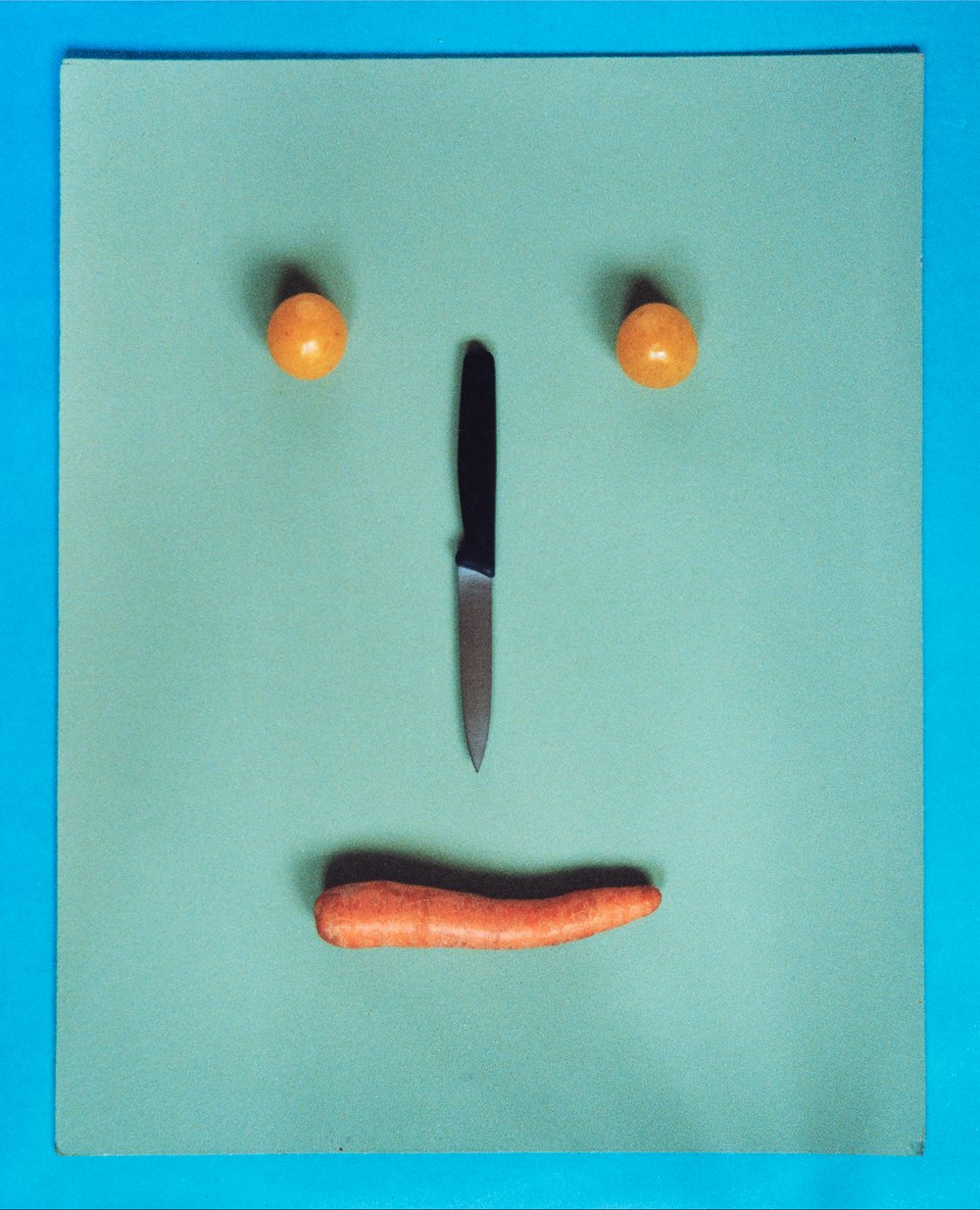

Leonid Borisov. Men, 1999. Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers. Gift of Dianne Beal and Paul Blue. Photo by Peter Jacobs

The exhibition ‘The Body Implied’ at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers in New Jersey offers a new perspective on the subject of the human body in the underground art in the last years of the USSR. Paradoxically it bridges the Moscow art scene of the late Soviet era with today, showing how this topic reverberates in post-Soviet Russia.

Curated by Stephanie Dvareckas, a Dodge Fellow at the Zimmerli Art Museum, the exhibition features iconic figures of Moscow Conceptualism such as Igor Makarevich (b. 1943), Vadim Zakharov (b. 1959) and Irina Nakhova (b. 1955). Many were born in different republics of the former USSR and came to Moscow to join its vibrant underground art scene. The exhibition draws mostly from the vast collection of the late Norton Dodge, an art patron with a passion for Soviet underground art, who bequeathed the treasures he amassed to the Zimmerli Art Museum.

Dvareckas explains the inspiration behind the exhibition. “I was thinking about the trend of performance art in the '60s and '70s, where artists were commiting violence on themselves and to their bodies. When I looked through the Dodge collection, a similar theme emerged. There were numerous examples of artworks in which the human body is only suggested and not actually visible or where the body is cut up or reconfigured or misconfigured in some sort of way.”

Many of the works that Dvareckas chose have rarely, if ever, left the vaults of the museum. However, even those that are better known reveal unexpected meanings and undertones when displayed in the context of the current exhibition.

Vagrich Bakhchanyan’s (1938–2009) photocollages, showing human figures in a state of surreal disintegration or substituted by an empty space, offer a portal to an otherworldly dimension of the absurd. Makarevich’s photographs of distorted plaster casts of his face challenge our notions of identity. In ‘Rooms’, the installations Nakhova created in her communal apartment, visitors are invited to experience new horizons in their perceptions of space with their bodies inside it.

Created during the period of political upheaval of perestroika, these works transcend politics. Despite the lack of political freedoms, their creators enjoyed a freedom of spirit and were able to find refuge from the harsh late Soviet reality in a magical realm of unbounded creative experimentation. The disappearing body can be perceived as a symbol of oppression yet at the same time it can be seen as a sign of inner freedom, representing a refined aesthetic escapism. Underground artists in the USSR could not escape the oppressive regime physically yet they could do so in their art, ignoring the regime and its constraints.

Eventually, this proved to be a winning strategy. In the years of perestroika, liberal-minded officials recognized the power of unofficial art as a tool of cultural diplomacy and as a means to earn some much-needed foreign currency for the collapsing Soviet economy. A now legendary1988 Sotheby’s auction in Moscow marked a moment of triumph as forbidden art emerged from the underground. For many artists, this marked the launch of what became successful international careers.

Yet the centrepiece of the present exhibition dates from a later era and offers a totally different approach, an installation by Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya, b. 1969). Called ‘Clothes for the Demonstration against False Elections of Vladimir Putin’ (2011–2015), it consists of pieces of clothing adorned with real slogans seen at protest rallies. The garments are attached to poles to be carried as banners along the streets. This choice of medium gives political protest a warm, tactile and personal dimension. Yet it can also be perceived as a symbol of the futility of protest. Deprived of the human flesh that should fill them, the clothes hang empty and hollow, like the slogans that are hand-written over them. Taken out of context, some seem even absurd to today’s viewer, their precise meaning lost and forgotten over time. A case in point is the passionate plea, “Bring Back the Baths!”

To a viewer familiar with Russia’s recent history, the installation vividly recalls the street rallies of 2011–2012 in Moscow, when up to 100,000 protesters flooded the capital’s central streets and squares. These protests led to nothing, and over the ensuing years the absence of the body became physical, not imaginary. Most of the artists whose works are on show at the Zimmerli are either dead or have left the country. Nakhova has been living in the U.S. for years. Gluklya is in the Netherlands. Vadim Zakharov is in Germany, Igor Makarevich in Czech Republic, and Sergei Anufriev (b. 1964) has returned to his native Ukraine.

The recent emigration wave of 2022–2023 is unprecedented in 21st century Russia and has led the national art scene to become physically bare and hollowed out. The images of disappearing bodies created during the hope-filled years of perestroika and the social upheaval of the early 2010s have acquired an entirely different meaning now: they look like a premonition.

The Body Implied: the Vanishing Figure in Soviet Art

Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

March 6 – July 31, September 4 – September 29, 2024