Uzbekistan’s Avant-garde Masterpieces in Major Italian Dual-venue Show

Uzbekistan: the Avant-Garde in the Desert. Light and Colour. Exhibition view. Florence, 2024. Photo by Andrea Paoletti. Courtesy of Ufifizi Galleries

The Palazzo Pitti in Florence and Ca’ Foscari University in Venice have joined forces to showcase ‘Uzbekistan: Avant-Garde in the Desert’. With more than 150 works from the late 19th century until 1945 it reveals rich cultural exchanges between Central Asia and Russia. The works on show have come from the Tashkent Museum of Art and the Savitsky Museum Collection in Nukus, in Karakalpakstan.

The Palazzo Pitti rises from its city square location in Florence, a monumental fortress under the camouflage of a laconic rustic Florentine façade. Entering through the courtyard, visitors find themselves within a maze of palatial interiors replete with frescoes, mouldings, sculpture and works by Titian, Raphael, Caravaggio and other great masters. Finally, having navigated the ‘mezzonino’, a procession of small halls, you arrive in the charming intimacy of the Palazzo setting that houses ‘Colour and Light’, one half of the ‘Uzbekistan: Avant-Garde in the Desert’ dual-venue exhibition organised in Italy by Uzbekistan’s Foundation for the Development of Culture and Art. The other venue is the halls of Ca’ Foscari University in Venice.

It is a first-ever European show bringing together works from the collections of the Tashkent Museum of Art and that of the undeniably unique and in so many ways extraordinary Nukus Museum of Art, named after its founder-director Igor Savitsky (1915–1984), a Kyiv-born painter and archeologist. The bifurcated show vividly illustrates the at times eccentric convergences and intersections of abstract and figurative art.

Spanning the late 19th century up to 1945, ‘Colour and Light’ reflects the multifaceted history of the relationship and cultural interactions between Turkestan and the Russian Empire, and, post-1917, those between the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (today’s Russian Federation) and the republics of Soviet Central Asia.

Between them, the two exhibitions comprise more than 150 works of Russian and Turkestan avant-garde art from the first third of the 20th century, including paintings, works on paper, and traditional arts and crafts which Savitsky had collected. It is presented loosly over three time frames, starting from the end of the 19th century, when academic artists like Vassily Vereshchagin (1842–1904) and Ivan Kazakov (1873–1935) first arrived in Turkestan. This period is associated with the colonisation of Central Asia and reflects ethnographic interests typical of European Orientalism. The second period began in the 1910s, when artists of different nationalities initially having studied in Moscow and St. Petersburg, under the influence of avant-garde artists at the VKhUTEMAS (Higher Art Technical Studios) and VKhUTEIN (Higher Art Technical Institute) art schools, introduced European modernism and the Russian avant-garde to the region, combining the two with local traditions. The result was the birth of a new formal language. The third period began in the second half of the 1930s, when the experiments of the avant-garde came to an end and Socialist Realism became a singular canon in art.

Italian curators Silvia Burini and Giuseppe Barbieri determined to revise the idea of the relationship between the Turkestan and Russian avant-garde as ‘metropolis’ and ‘periphery’, making Central Asia the point of reference and the main attraction. Zelfira Tregulova, formerly a director of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was taken on as a consultant for the exhibition. The curators put forward the term ‘Avanguardia Orientalis’ to describe the synthesis of early 20th century modernism – European, Russian and Turkestani – that they sought to reflect, stressing the originality, uniqueness and value of what the avant-garde had to offer but always to ensure that the local cultural context remained paramount.

‘Avanguardia Orientalis’ was characterised by its multi-ethnicity – Russian, Ukrainian, Jewish, Armenian artists and representatives of many other nationalities lived and worked in the region. The influence of Islamic traditions in art, architecture, music and textiles, surprisingly echoed the experimental research and formal language of the avant-garde.

An animated film about the artists and their artworks, projected on the walls of the Palazzo Pitti to the meditative rhythms of traditional folk music, serves as a kind of portal, transporting the exhibition goers into the specific atmosphere. Despite a lack of space and crowded hanging, the exceptional artistic quality and originality of the works makes the viewer forget about any shortcomings and plunges them headlong into the contemplation of ‘colour and light’, allowing them to savour the finest details and incredible diversity of the artistic styles on display.

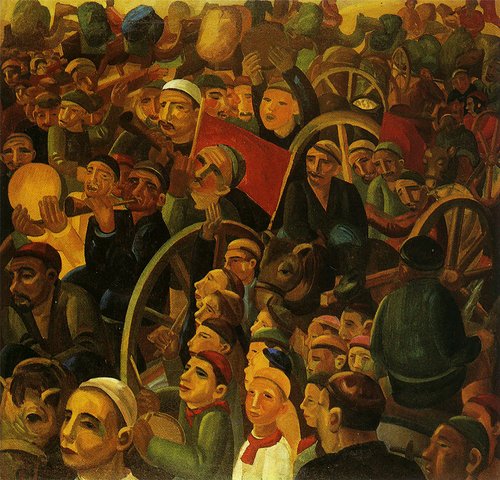

Here, the emphasis is on the ‘Turkestan avant-garde’. The exhibition opens with ‘Bull’ by Vasily Lysenko (1899–1974), who was born in Orenburg and moved to Tashkent in 1922. Lysenko’s formal experimentation with various avant-garde trends plus the mysticism in his art led to his arrest in 1935. In this section, views and mise-en-scenes inspired by the life of the inhabitants of Bukhara and Samarkand predominate. Here, paintings by Ivan Kazakov (1873–1935), Nikolai Grigoriev (1890–1943), Pavel Benkov (1879–1949), and Nikolai Karakhan (1900–1970) reflect an evolving shift in style from pure ethnography to full-blown ‘Avangardia Orientalis’. These vivid depictions of local scenes of work and rallies are notable for their unexpectedly light lyrical painting and subtle transitions of pastel colours. Also featured here are paintings by Igor Savitsky.

In the first third of the 20th century, Central Asia was to become a Mecca for many artists. It enabled them to continue their experimentations with vibrant colour, combining the legacies of Fauvism, Paul Cezanne and local traditions like textiles and miniature painting, as they explored light and form, even amidst times of political and social turbulence.

In Florence, the exhibition juxtaposes paintings and exquisite works on paper by Alexander Volkov (1886–1957), Ural Tansykbaev (1904–1974), Alexander Nikolaev (also known as Usto Mumin, 1897–1957), Nadezhda Kashina (1896–1977), Viktor Ufimtsev (1899–1964), Zinaida Kovalevskaya (1902–1979) and many others with chapanes (Ikat jackets), traditional headdresses, Suzani (embroidered textiles), and ornamental fragments of decorative trimmings of yurts. The Palazzo Pitti show concludes with ‘Drowned’, a Boris Golopolosov (1900–1983) expressionist work from the Savitsky collection, a fitting symbol of the tragedy that cut short the life of the avant-garde in the USSR.

Robert Falk (1886–1958), the only representative of the Russian avant-garde featured in the Palazzo Pitti exhibition, acts as a key artist linking the Florence show to its ‘Form and Symbol’ counterpart in Venice. Falk, who, having spent time in France, felt insecure on his return to Moscow, arrived in Central Asia in 1938. Evacuated to Samarkand during the Second World War, he became one of Igor Savitsky's teachers, along with Konstantin Istomin (1887–1942) and Nikolai Ulyanov (1875–1949). It was Falk who proved to be crucial figure, literally serving as a ‘channel of transmission’ for European and Russian modernism.

Ca’ Foscari, with its characteristic Venetian architecture featuring lancet windows echoing the Orient, and its picturesque courtyard, serves as a perfect prologue to ‘Form and Symbol’. The exhibition is profound and perfectly designed, with an emphasis on the dialogue, pursuit of new forms, and the experimentalism, inclusiveness and multiculturalism that were so characteristic of the avant-garde in the first third of the 20th century, both abstract and figurative.

The exhibition in Venice is dedicated to the later decades of this period, and this is best illustrated by the inclusion of works from the collection of the Tashkent Museum of Art, reflecting the Soviet state’s 1921 transfer there of fifty-nine works by leading avant-garde artists.

The display in Venice includes paintings by Aristarkh Lentulov (1882–1943), Ilya Mashkov (1881–1944), Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Ivan Kliun (1873–1943), Aleksandra Ekster (1882–1949), Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), Nadezhda Udaltsova (1885–1961), Lyubov Popova (1889–1924), Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958), among others. Outstanding graphic works by Vera Pestel (1887–1952) and Lyubov Popova from the Nukus collection are on view as well.

The exhibition compares these pieces with iconic works by Ural Tansykbaev (1904–1974), Alexander Volkov (1886–1957), Nikoli Karakhan (1900–1970), Mikhail Kurzin (1888–1957), Ilya Mazel (1890–1967), Victor Ufimtsev (1899–1964), Elena Korovai (1901–1974), Nadezdha Kashina (1896–1977) and Hovhannes Tadevosyan (1889–1974) from the Nukus Museum and traditional decorative and applied art, which brings a symbolic element. Special attention is paid to the surrealist and expressionist movements, Savitsky's great love, which often remains overshadowed by the glory of objectless art, far from the spotlight of Western curators.

The real sensation of the Venice exhibition is the room devoted to the Amaravella group (1923–1928), which features works by the group’s leader Pyotr Fateyev (1891–1971), as well as by Vera Pshesetskaya (1879–1946), Alexander Sardan (1901–1974), Sergei Shigolev (1895–1942?), Boris Smirnov-Rusetsky (1905–1993) and others. Formed in Moscow, this group was influenced by and dedicated to the esoteric cosmism of Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947). According to the curators, Vasily Lysenko’s mystical semi-abstract paintings are stylistically close to Amaravella.

Among the most striking, expressively memorable images on show here are Hovhannes Tadevosyan's ‘Malaria’, Ural Tansykbaev's ‘Portrait of an Uzbek’, Alexei Rybnikov's (1887–1949) ‘Northern Lights’, portraits by Alisa Poret's (1902–1984), and Mikhail Kurzin's ‘Capital’, which evokes the style of the German Expressionists of the 1920s-1930s.

The Venice and Florence shows, although connected, are distinctive. The Palazzo Pitti arm presents a meditative and lyrical line. In contrast, the Ca’ Foscari curators offer a dynamic history of the period of ‘Sturm und Drang’, a reminder of the active experimentation and art activism in the Central Asian region, a moving testament to the difficulties of life-building and affirmation of the new associated with the avant-garde movements in Europe and Russia.

Coincidentally if surprisingly, the concept of the exhibition and its visual range align with the Venice Biennale’s theme of ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ and its main curatorial project with its lavish display of Islamic, Latin American, Asian modernism and indigenous works. Both represent a call to shift the focus of attention to previously unexplored pages of art history that can overturn established notions of modernism.

Uzbekistan: the Avant-Garde in the Desert. Light and Colour

Florence, Italy

April 16 – June 30, 2024

Uzbekistan: Avant-Garde in the Desert. Form and Symbol

Venice, Italy

April 17 – September 29, 2024