The Deep-Seated Fears of Pavlov-Andreevich

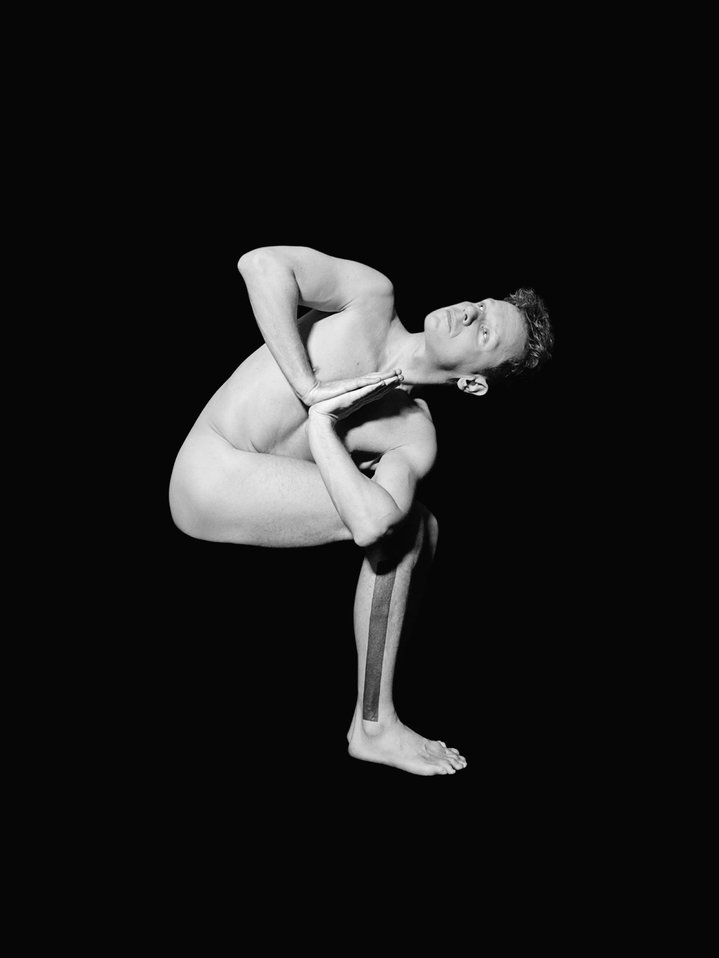

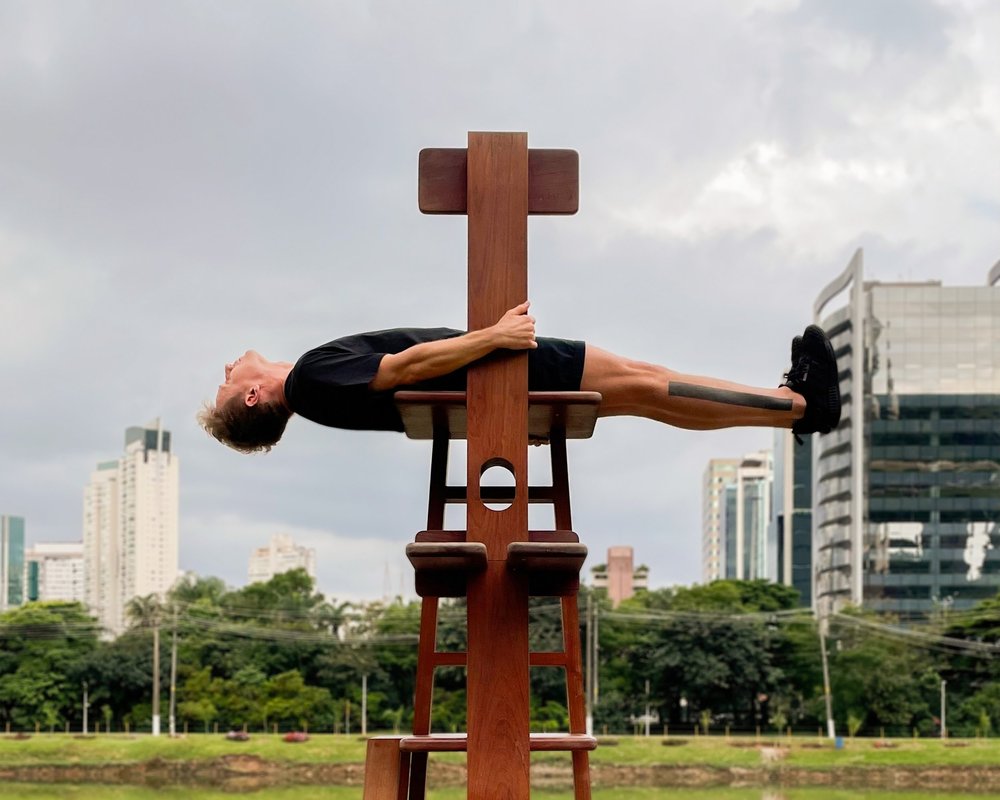

Fyodor Pavlov-Andreevich. Centipede, 2023. 'Antifurniture' series. Photo by Olga Treivas. Courtesy of the artist

Russian-born performance artist Fyodor Pavlov-Andreevich has created an ensemble of performative sculptures called ‘Antifurniture’ which are currently installed at the Design Museum in London inviting us all to face our fears in public.

This Autumn, the London art-going public is embracing performance art with enthusiasm, judging by the weekday crowds attending Marina Abramovic’s long-awaited retrospective at the Royal Academy and people young and old thronging the atrium at the Design Museum where Pavlov-Andreevich’s (b. 1976) large interactive works are on view. Perhaps it should not surprise us as, not without irony, in the wake of instantaneous, global communication and the great social media revolution, we find ourselves today living collectively everywhere in social straightjackets in which it has become risky to make any big statements in public, and where our state art institutions are run by administrators not to mention health and safety officers. For performance artists, many of whom address the tabooest of subjects and commit themselves to horrific acts of physical self-harm, it is not a climate conducive to their art.

Just this September, in an interview for Vogue Magazine, Marina Abramovic (b. 1946) confessed that the kind of performances she did in the 1970s would not be possible today – perhaps thankfully as it was a member of the audience that saved her life in 1974 during a stunt where she lay prone inside a five-pointed Star and nearly asphyxiated. Today at her RA retrospective in London, original performances are now re-enacted by students who study performance at Abramovic’s eponymous institute, their stints are shorter, there are psychologists and nutritionalists on hand in the gallery behind the scenes, the union dictates working hours. It is a more sanitised version of performance art for our times.

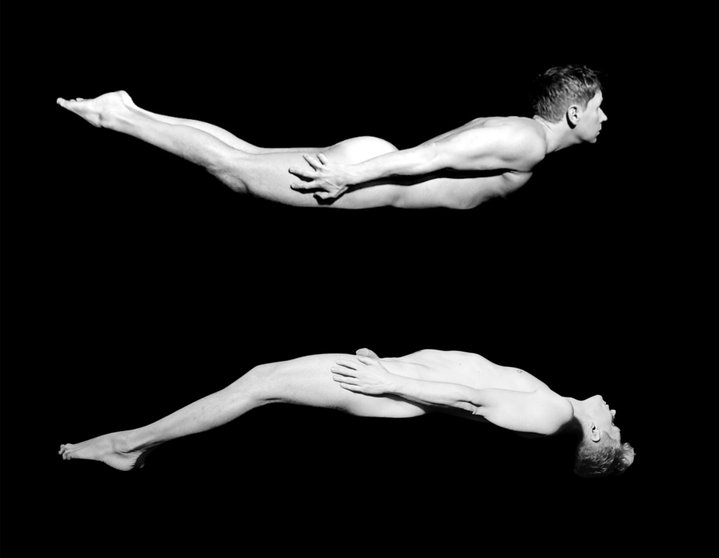

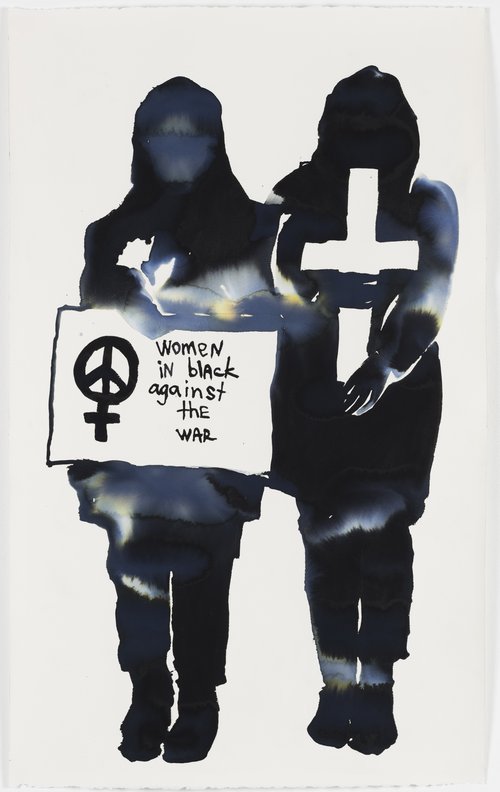

Abramovic has long been a figurehead in this discipline, her works inspired many artists, Pavlov-Andreevich among them. I first had the privilege of seeing him in action as a fledgling performance artist in London at Paradise Row gallery in 2009, in a work called ‘I Eat Me’ bravely addressing the painful subject of suicide. It was an exceptionally assured performance, nothing like a rehearsal despite his relative lack of experience. He crouched naked on the gallery floor and talked in a stream-of-consciousness monologue for five days, it was both disturbing and transformational in its power and energy, and even today it is still vividly etched in my memory. Later Pavlov-Andreevich left Russia to settle in Brazil, and I only saw him the last time five years ago at Gazelli Art in London naked but wrapped in a rug and suspended from the gallery roof for five hours, hanging over the pavement. It was a stunt to raise awareness of LGBT rights in the Russian region of Chechnya. It may not have been his most daring performance, but what he has assembled over nearly two decades is an impressive and varied body of work in which he has not shied away from pushing himself to the limits of endurance. In this he shares something of the bold, uncompromising spirit of his mentor Abramovic. But virtually all his work addresses head on contemporary political injustices across the world, and not only drawn from his close sphere of experience, it is not just a reflection of his own biography in the way that Abramovic’ work seems to grow organically from her. In this way, he can be compared with other Russian actionist artists such as Pavel Pavlensky (b.1984) and the members of Pussy Riot perhaps with a broader geographical focus.

Yet, unusually, alongside the gritty, tough and punitive side of his work, I have often seen something of the aesthete in Pavlov-Andreevich and when looking at this ensemble of nine wooden sculptural installations, or performative sculptures at the Design Museum, I am struck first by their visual appeal: they are beautifully made. Before you even get close to them, you notice their shapes, the smooth soft carving and polish of the wooden structures; when you leave them those first impressions remain and more, they are tactile and welcoming.

This, in spite of the fact that they are also essentially hostile. They may resemble beds and chairs, but, as the name goes, they are ‘Antifurniture’, their purpose is to take us out of our comfort zones, they are not an invitation to relax. At the Design Museum there are information panels beside each piece, with a gallery assistant encouraging visitors to participate, explaining what you are meant to do. They also ask you afterwards how you felt and encourage discussion, it is ostensibly all part of a holistic experience. Each piece of ‘Antifurniture’ addresses specific phobias, such as sociophobia (fear of meeting someone new), claustrophobia (fear of small spaces) and algophobia (fear of physical pain) among two dozen other phobias cited, many of which I have never heard of before although it turns out they are rather common.

In the interests of research for my article, I decide to try some out, and go first for the ‘Bunker-Bed’ which addresses the widespread social phobia of speaking with strangers. Minutes later, having climbed up a wooden ladder and lying horizontal on a smooth, curved wooden panel, I find myself staring into the eyes of an elderly French women who I have never met before and whose name I do not know. For two minutes we look into each other’s eyes through a hole, chanting a mantra in unison, something along the lines of ‘the value of the present lies in eternity’.

Like the ‘Bunker-Bed’, most of the performative sculptures not only invite our participation but encourage us to engage with someone else. It is no small thing: when do any of us actually stop and share an experience with a stranger? I also try out ‘Push-Me-Pull-You’ which is a bit like a large, wooden seesaw for grown-ups; the gallery assistant quickly finds someone to sit on the other end, both of us facing in opposite directions, bringing up questions around trust. Unless you are scared of heights, in which the ‘Centipede’ might send shivers down your spine, one of the most hostile pieces is called the ‘Leg Opener’, which was curiously not shown at the Design Museum but is currently installed at the house of London based art collectors Igor and Natasha Tsukanov, who have long been enthusiastic supporters of Pavlov-Andreevich. The form echoes a gynaecological chair, with stirrups, haunting, yet outside the usual context and with its smooth warm wooden surfaces, less threatening. According to the artist, one of the main aims of these sculptural pieces is to envelope the participant’s body and relieve them of their fears.

The works are fun to try out, and perhaps in some ways this undermines their serious message about how our collective social phobias can impact on our political realities, and on an individual level our well-being and relationships with others are harmed by deep seated fears. What they do achieve is open discussion around difficult subjects, encouraging us to talk about our fears with others and at the very least acknowledge our vulnerabilities with one another. And we all have the opportunity to briefly step in the shoes of a performance artist and put ourselves on display, we are both watcher and watched as we navigate the space. As an art expert even though I share that common ailment of being a frustrated artist, this is more a longing to paint fruit like Cézanne in front of an easel in a studio, than the desire to be rolled up in a carpet and hung from the roof. Long live performance art.