Soutine and Kossoff Displayed Side by Side on the English Coast

Chaim Soutine. The Little Pastry Cook, c.1927. Private Collection. Soutine/Kossoff. Hastings Contemporary. London, 2023. Courtesy of Christie's Images

There is a dialogue exhibition at Hastings Contemporary this Summer bringing together two artists Chaim Soutine and Leon Kossoff who have more than a passing resemblance.

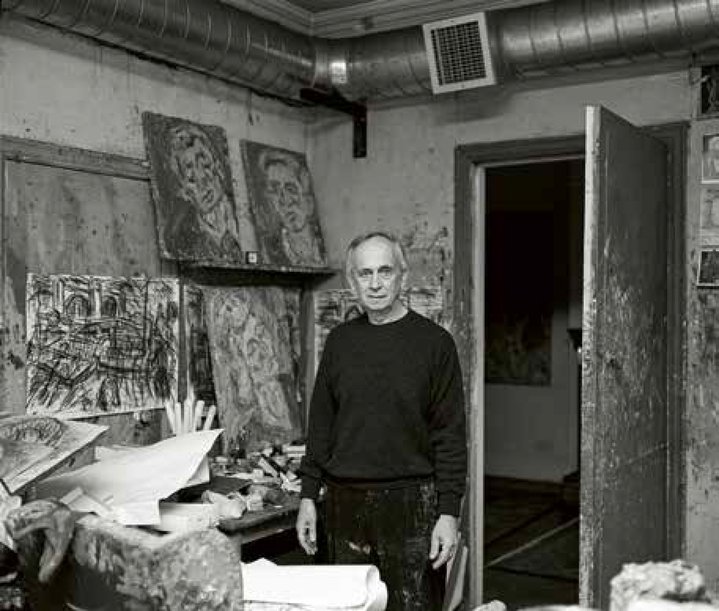

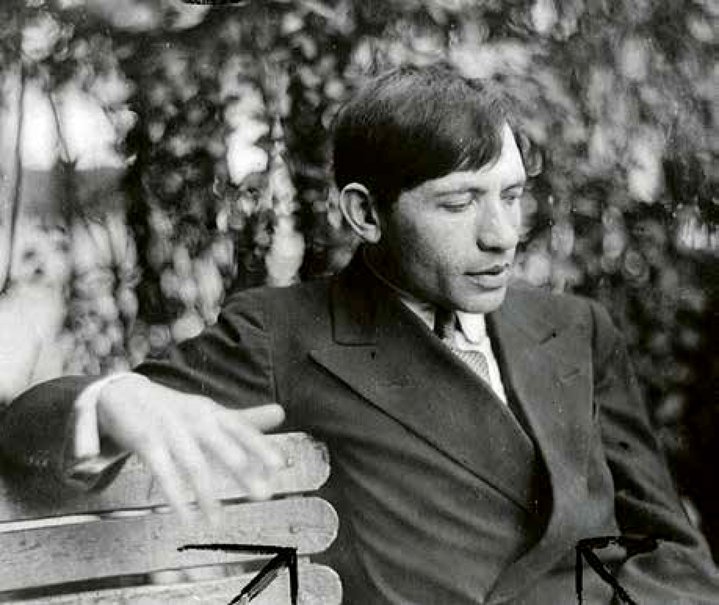

They never knew one another although their lives overlapped for nearly two decades until Soutine’s untimely passing in 1943. They were both Jewish working-class immigrants from Eastern Europe, Soutine was born in a small town near Minsk, now the capital of Belarus, and both of Kossoff’s parents left Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century to settle in London, where he was born one of seven siblings, in 1926. Both Chaim Soutine (1893–1943) and Leon Kossoff (1926–2019) are associated with expressionism outside the German mainstream: Soutine in France and Kossoff in post-war London. Both are easel painters, eschewing the avant-garde for figurative art and for whom an interest in the physical properties, colours and textures and characteristics of oil paint is central to their work.

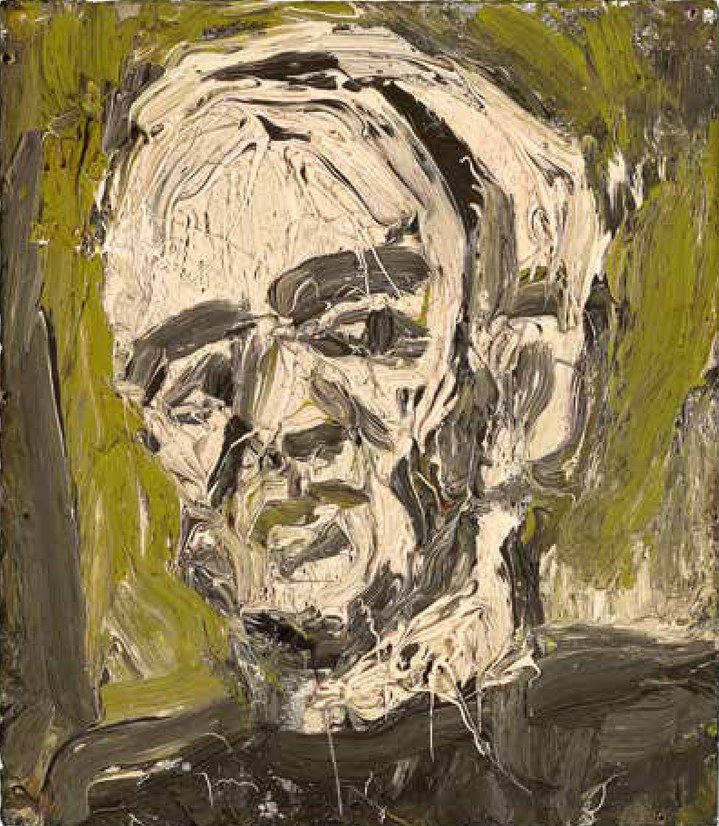

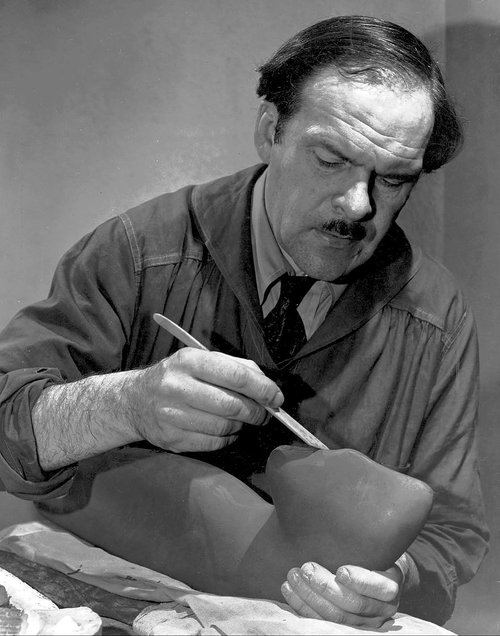

But perhaps this is as far as the similarities go. They came to their easel in very different ways. Soutine was always in a rush. His contemporary, the sculptor Channa Orloff (1888–1968) who knew him well described the speed at which he painted as ‘incredible’. Kossoff was full of deliberation and self-doubt, painting was about building up layers, erasing, and layering again. Even single brushstrokes were overloaded with paint, it is fascinating just to lean in and look at his paintings close-up.

Soutine and Kossoff straddled World War II, a divide which is often bluntly used to separate modernism with post-modernism in Western European and North American art history. Soutine has often been seen as a missing link between the two: the American Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Willem De Kooning (1904–1997) were greatly influenced by him, his work was known to American audiences through collector Albert C Barnes an early champion of his art, and whose patronage was crucial to Soutine’s reception back in France throughout the late 20s and 30s. But post-humously Soutine also exerted a huge influence on the post-war London artists, Lucian Freud (1922–2011), Francis Bacon (1909–1992) and perhaps more than those, Frank Auerbach (b. 1931) and Leon Kossoff, both of whom had been students of David Bomberg (1890–1957) in London (and who as painters are peas in a pod, Auerbach called themselves ‘two mountain climbers roped together’).

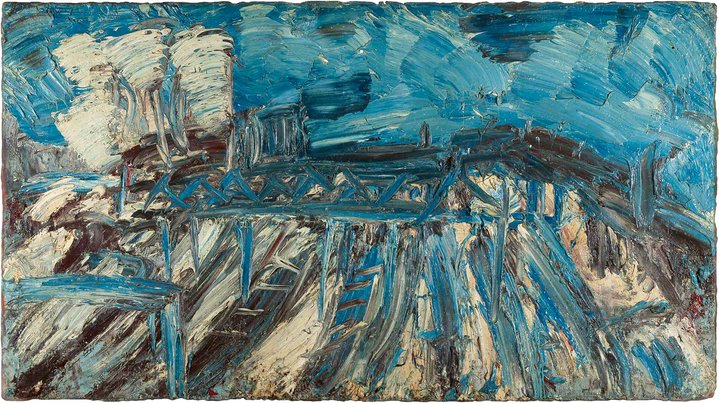

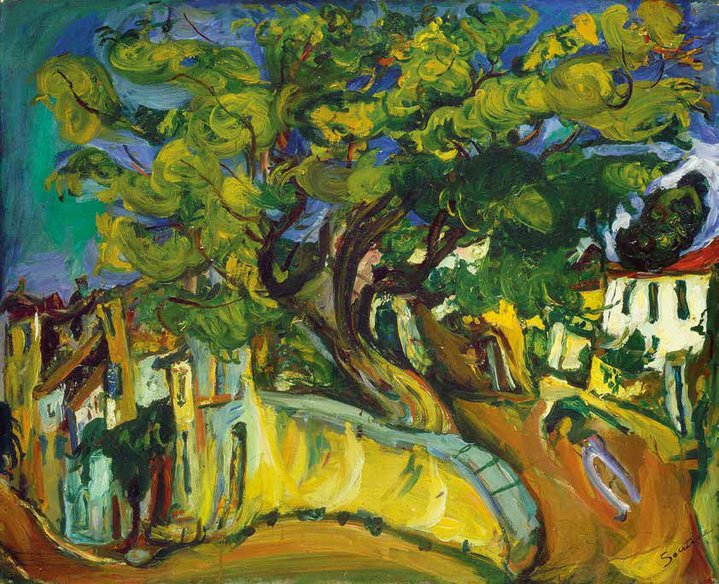

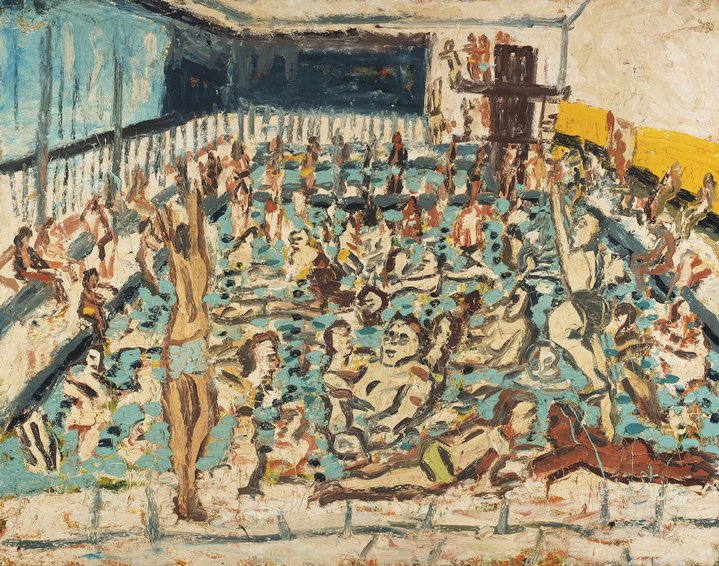

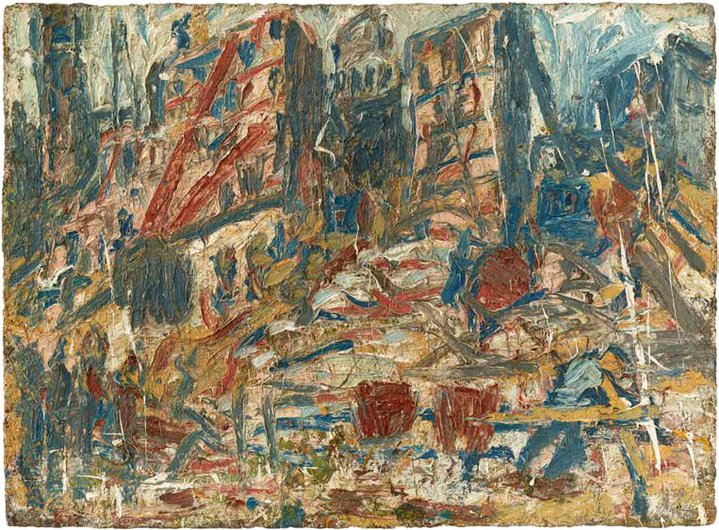

The Soutine/Kossoff show at Hastings Contemporary comes in a year of important dialogue exhibitions in Western Europe: in Paris at the Musee d’Orsay there is Manet/Degas; in London at Tate Hilma Af Klimt/Piet Mondrian; and they come on the back of the Monet/Mitchell show at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris last year. At their best, these paired shows give curators the opportunity to highlight little known dimensions and put forwards novel interpretations in the work of artists we think we know. Since the successful show in London of Soutine’s portraits ‘Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys’ at the Courtauld in 2017/18, and the strident market for his portraits which fetch far more than his landscapes on the art market, it is easy to become blasé about his landscapes. Yet it is Soutine’s landscapes, particularly those he painted during his stays in Céret, that paved the way for American Abstract Expressionism, emotive landscapes that reach into abstraction, although never quite going all the way. For all their exaggeration and distortion his portraits seem less radical. This cannot be said for Kossoff’s portraits in the Hastings show, haunting figures with a fleshy human presence captured in few brush strokes, pushing the boundaries of abstraction like his 1959 ‘Head Leaning on a Hand’ which is barely legible as an image.

The theme of the show is ambitious for a small, provincial gallery, a triumph of Arts Council England’s investment in contemporary art centres outside London. That it gives local audiences the chance to learn about two extraordinary artists who themselves are in many ways underappreciated is, I think, this show’s highest achievement and a worthy one. And the paring of Soutine with one artist from the London School is a progressive step from more generalized comparisons that are often referenced but little studied in detail. On a downside, the artists’ works are exhibited in separate rooms, so there are no opportunities to compare them side by side. Where it also falls short, behind the superficial aesthetic similarities, is a lack of probing into their wider art practices, for example, their attitude to drawing could not be more different and this is left unexplored. Kossoff was a natural draughtsman, and drawing remained central to him throughout his long career, he once wrote that “I think of everything I do as a form of drawing”. He only started work on his larger compositions after making copious sketches; he spent many hours over five decades in the National Gallery in London drawing after the Old Masters, Rembrandt, Poussin, Goya, attending and documenting many of the blockbuster temporary exhibitions staged there. It is hard to believe - but true - that Soutine did not draw anything.

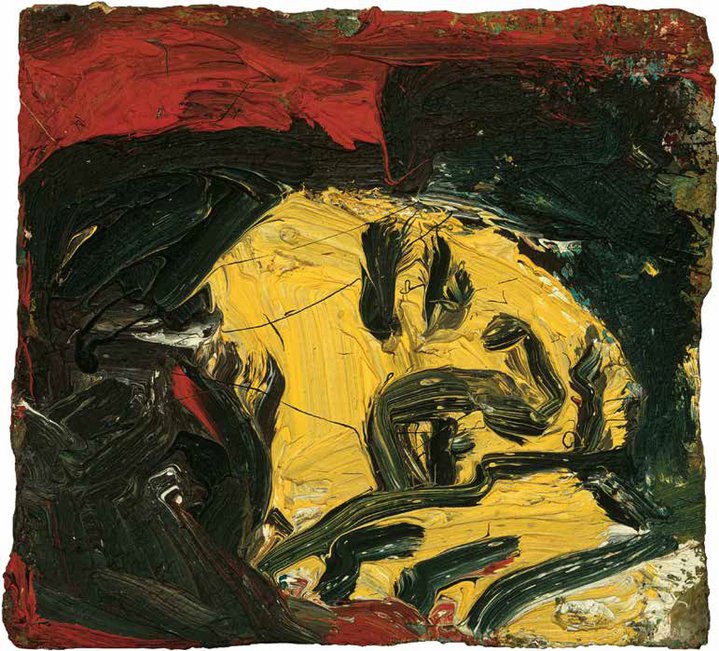

Taken together, Soutine and Kossoff give us something of a history lesson of the 20th century. You start in a room festooned with tormented, dark, anguished paintings bordering on a kind of madness done by Soutine in Céret in the early 1920s, what MoMA’s eminent first director Alfred Barr called Soutine’s “crazy, twisted landscapes”. Then you proceed through the rooms to meet Kossoff’s pictures of post-war London, giving one pause for thought - demolished buildings, building sites, even the summer paintings are dark. It is a story of before and after.