Serpukhov shines at the new Moscow Region Biennale

Galina Smirnskaya. The fabric of Time. Exhibition view. The First Biennale of Visual Arts ‘The Art of Seeing. Avant-garde'. Serpukhov, 2024. Courtesy of Serpukhov Museum of History and Art

The new Moscow Region Biennale spotlights a fascinating museum in the small town of Serpukhov and explores novel connections between the Russian avant-garde and contemporary art. At the same time, a parallel exhibition casts new light on the extravagant religious beliefs of renowned Soviet sculptor Sergei Konyonkov.

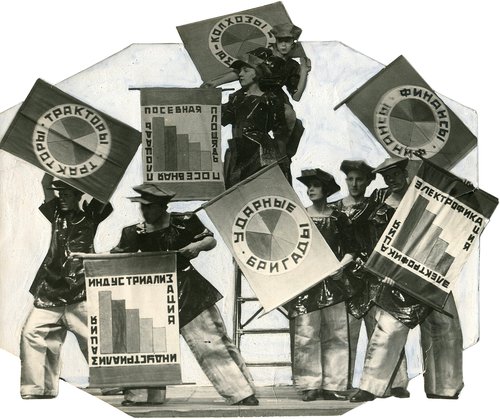

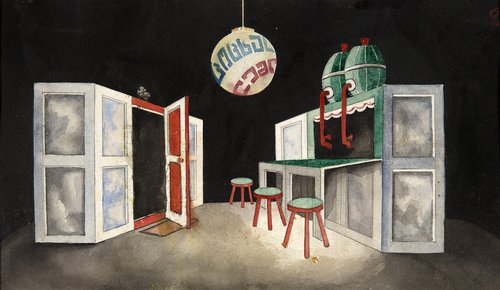

The main event of the Serpukhov First Biennale of the Visual Arts ‘The Art of Seeing. Avant-garde’, an exhibition curated by Alina Saprykina and Marina Fedorovskaya perfectly defines the mission of the newly created Moscow Region Biennale. Called "Avant-Garde: The Workshop of the Future", it combines works by both early 20th century modernist and contemporary artists from Russia as opportunities today to show live Western art projects in Russia are next to none. Necessity being the mother of invention, the domestic art scene has turned increasingly to deeper and broader explorations of its own canon and traditions.

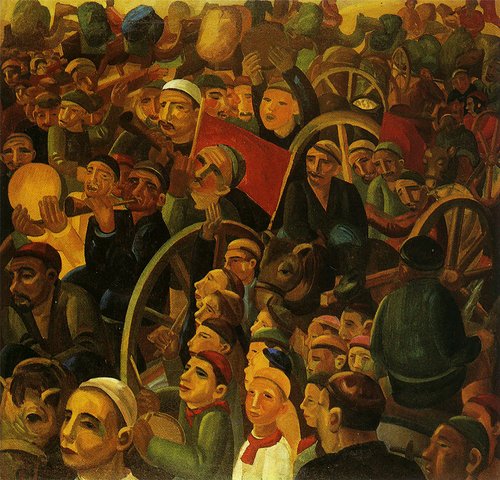

This new exhibition features paintings by Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964), David Burliuk (1882–1967), Robert Falk (1886–1958), Ilya Mashkov (1881–1944) and other painters of the first half of the 20th century. Their works are hung alongside those of Natalia Arendt (b. 1959), Maria Arendt (b. 1968), Roman Ermakov (b. 1985), Irina Korina (b. 1976), Alexei Luka (b. 1983), Andrei Lublinsky (b. 1972), among others. The latter group mostly comprises artists from Moscow and St Petersburg, working in a wide variety of different media from embroidery to sculpture. Paintings by Russian avant-garde artists come from the collection of the local museum itself, whereas the contemporary works come directly from the artists or the galleries that represent them.

Serpukhov is a small town one hundred kilometres to the south of Moscow, nestled in picturesque hills near the confluence of the Nara and Oka rivers and is known for its two monasteries and railway bridge. Thanks to its unique collection of icons and a decent collection of Russian avant-garde as well as an intriguing department of European paintings, the Serpukhov Museum of History and Art is considered one of the best museums in the Moscow region.

An interesting curatorial approach has the Moscow region exhibition engaging in a dialogue with two summer blockbuster shows in the Russian capital: ‘Square and Space’ at GES-2 and ‘Jewish Avant-Garde’ at the Jewish Museum, and the Moscow region is no less wealthy a cousin in this artistic exchange. Viewers are transfixed by a 1920 painting by Alexei Levin (1893–1967) called ‘Handkerchief on the Table’, which combines Kazimir Malevich's black square with the still-lifes of David Shterenberg (1881–1948). Similarly, the work of Alexei Levin, a half-forgotten artist, gains new power and relevancy when placed in dialogue with the work of a new generation of artists such as Kristina Malysheva and her ironic carpet ‘Black Square’ (2023) or Ilya Derzaev and his meditative video ‘Flow’ created in 2017. Irony, one of the strengths of ‘The Art of Seeing’ seems more relevant than the pathos of mega-projects.

The exhibition makes no distinction between art and design, original and copy, replica and unique piece, a fundamental difference that separates it from so many projects in the field of contemporary art. A suprematist porcelain edition is shown next to Dmitri Aske's (b. 1985) ‘Blue Bird’ (2020), made out of plywood covered with white acrylic paint in a glass vitrine it looks indistinguishable from porcelain. This intentional blurring of boundaries seems deliberately designed to lead the viewer to conclude that artistic vision is more important than method, form or the aura of authenticity. The very thought, while alien to artists of the Russian avant-garde, is close to that of Russian modernist literature.

The location for the first Moscow Region Biennale was not a random choice on the artistic map of Russia. The Serpukhov Museum, which originally housed the private collection of a merchant Anna Vasilyevna Maraeva, was nationalised in 1919. In 1893, she bought the entire private art collection of Yuri Vsevolodovich Merlin, who, at the time, possessed one of the best collections of Western painting in Moscow. Maraeva, however, viewed the purchase as merely a means of capital investment and so kept the paintings in a warehouse on her country estate.

Maraeva’s approach to icon painting was completely different. Between 1908-1910, she built a small chapel next to her house in memory of her daughter, which housed her collection of rare ancient icons. The chapel was funcioning until 1989, with the exception of a brief period during the Second World War. Today it is a uniquely integral monument, the only one of its kind among the museums in Russia. Like many wealthy Russian merchants and manufacturers, Maraeva came from a family of Old Believers. They were members of the bezpopovtsy, a radical religious community who staunchly rejected the modern priesthood, believing in the 17th century that the Antichrist already ruled the world.

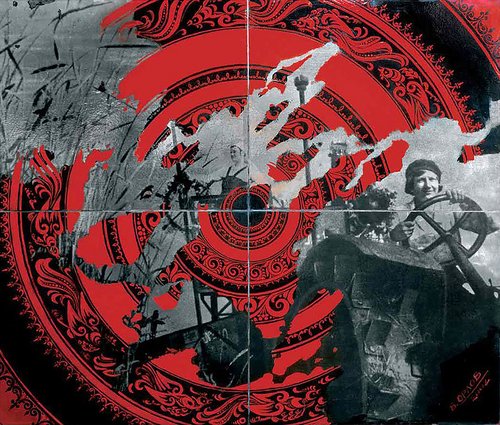

On view at Serpukhov, works by renowned Soviet sculptor Sergey Konyonkov (1874–1971), who, only many years after his death, was revealed to have been an admirer of Charles Taze Russell, founder of a sect known as the ‘Bible Explorers’ which later became known as the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Konyonkov lived in the United States from 1924 to 1945. His drawings show familiarity with the apocalyptic doctrines of the late 19th century Adventists, a group from which Russell sprang. The sculptor was also conversant with similar fascinations of the bezpopovtsy. Konenkov's ‘Apocalyptica’ is now on display for the first time at the Serpukhov Museum, along with his sculptures, including two portraits ‘Marfinka’ and ‘Ninotchka’, for which the artist received the Stalin Prize in 1951.

Konyonkov’s religious quest is reflected in his drawings on themes from the Apocalypse, the most striking of which is a portrait of Joseph Stalin as the winged King of Babylon appearing under a red banner. The sculptor believed that when it came to the USSR, “the kingdom of God is established on the basis of justice" and the Red Army is the Army of God.

The First Biennale of Visual Arts ‘The Art of Seeing. Avant-garde'

Serpukhov Museum of History and Art

Serpukhov, Russia

June 29 – September 29, 2024

Konyonkov. Prophet and Genius Sculptor

Serpukhov Museum of History and Art

Serpukhov, Russia

July 3 – November 10, 2024